JAZZ.

Rene Matić / Oscar Murillo

14 Mar - 28 Jul 2024

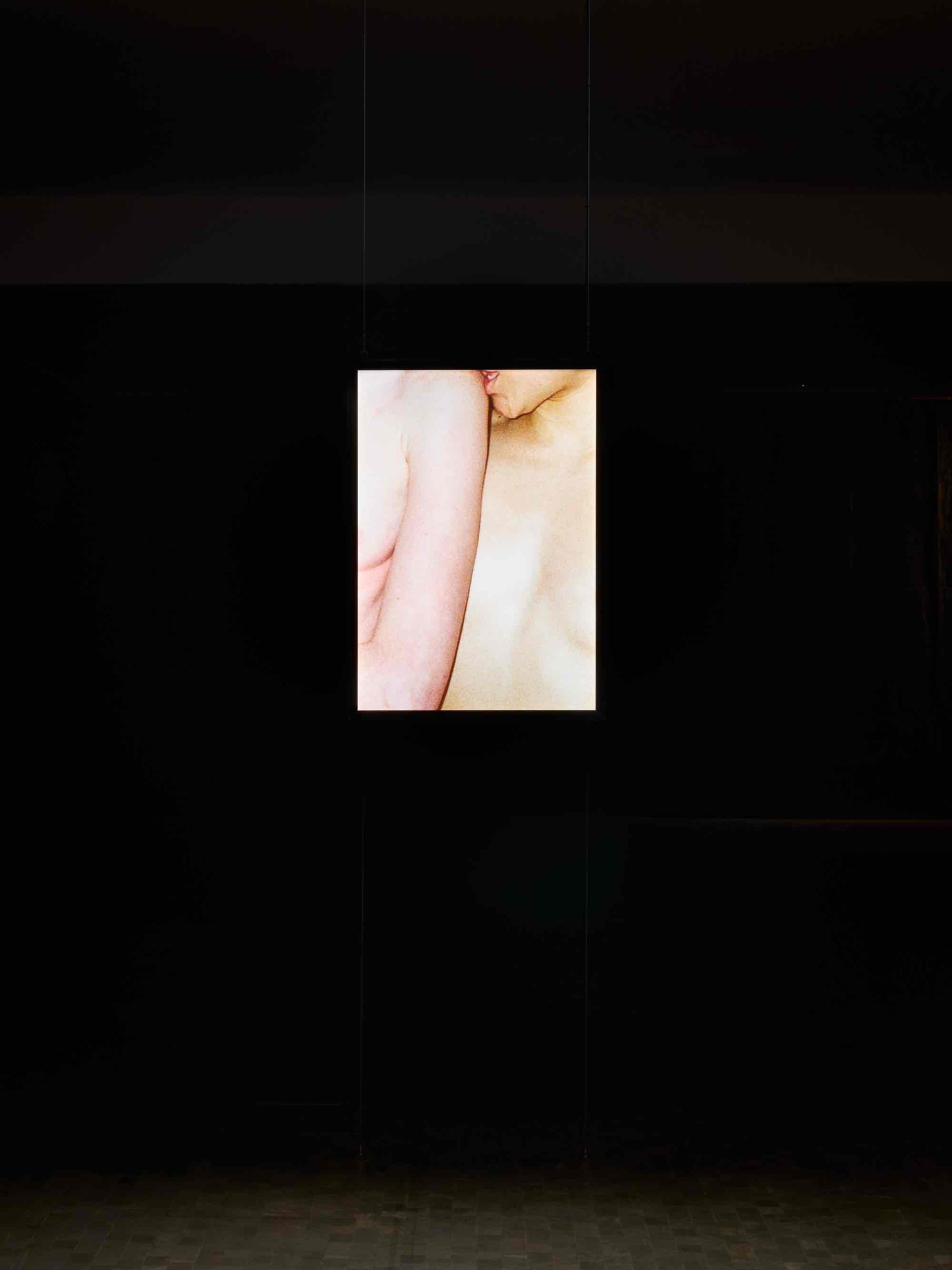

Installation view: Rene Matić / Oscar Murillo. JAZZ., with works Oscar Murillo, Kunsthalle Wien 2024, photo: Tim Bowditch and Reinis Lismanis, courtesy the artist

Installation view: Rene Matić / Oscar Murillo. JAZZ., with works Oscar Murillo, Kunsthalle Wien 2024, photo: Tim Bowditch and Reinis Lismanis, courtesy the artist

Installation view: Rene Matić / Oscar Murillo. JAZZ., with works Oscar Murillo, Kunsthalle Wien 2024, photo: Tim Bowditch and Reinis Lismanis, courtesy the artist

Installation view: Rene Matić / Oscar Murillo. JAZZ., with works Oscar Murillo, Kunsthalle Wien 2024, photo: Tim Bowditch and Reinis Lismanis, courtesy the artist

Installation view: Rene Matić / Oscar Murillo. JAZZ., with works Oscar Murillo, Kunsthalle Wien 2024, photo: Tim Bowditch and Reinis Lismanis, courtesy the artist

Installation view: Rene Matić / Oscar Murillo. JAZZ., with works Oscar Murillo, Kunsthalle Wien 2024, photo: Tim Bowditch and Reinis Lismanis, courtesy the artist

Installation view: Rene Matić / Oscar Murillo. JAZZ., with works Oscar Murillo, Kunsthalle Wien 2024, photo: Tim Bowditch and Reinis Lismanis, courtesy the artist

Installation view: Rene Matić / Oscar Murillo. JAZZ., with works Oscar Murillo, Kunsthalle Wien 2024, photo: Tim Bowditch and Reinis Lismanis, courtesy the artist

Installation view: Rene Matić / Oscar Murillo. JAZZ., with works Oscar Murillo, Kunsthalle Wien 2024, photo: Tim Bowditch and Reinis Lismanis, courtesy the artist

Installation view: Rene Matić / Oscar Murillo. JAZZ., with works Oscar Murillo, Kunsthalle Wien 2024, photo: Tim Bowditch and Reinis Lismanis, courtesy the artist

Kunsthalle Wien presents Rene Matić (b.1997, Peterborough, UK) and Oscar Murillo (b. 1986, La Paila, Colombia) together for the first time.

For JAZZ. both artists present existing works as well as new commissions made specifically in response to the space and the city of Vienna. Encompassing painterly gestures, installation, film, photography, and sound, each element on show is in dialogue, shaped by Murillo’s black canvas installation which is suspended from the ceiling throughout the space.

Together, through dissection and reconciliation, both artists explore the impossibilities and contradictions that arise from notions of desire, visibility, and opacity.

Coming from differing vantage points and mediums, both artists employ gesture and abstraction within their practices. Murillo chooses the social over the subjective and the collective over the individual, while Matić’s practice is often grounded in the personal. Murillo’s works, and even titles, often reference the act of sending messages or of recording, intercepting, and tuning into, while Matić displays a deep concern with the reception of the image. Murillo’s paintings and drawings come to life through mark-making and gesture; Matić’s works use dance as a form of expression within the realm of the moving image and photography. In this sense, JAZZ.—a title that evokes many resonances and qualities within each artist’s practice—could be understood as a mode of artistic collaboration but also of reception: one where cultural sensibilities are blended, improvisation takes place and group interaction becomes as vital as the individual voice. JAZZ. nods to concepts of desire, of consumption of the Other, it plays with performativity while retaining the right to opacity.

While in some ways the practices of Matić and Murillo seem rather complementary to one another, they also overlap in important aspects. For instance, the gestural painting, reminiscent of action painting, that is so often at the heart of Murillo’s work is akin to the use of dance and dancing in Matić’s videos, as they both share a spontaneous, unbothered, and unscripted nature. Both artists also share intuition within their process and production, a calculated intuition. One could say intuition deployed strategically. Additionally, both artists succeed in carving out a space of independence for themselves in a cultural context that is determined to classify and smooth out everything and everyone. Claiming such a space first entails an act of “disaffiliation” (concept by Édouard Glissant), through which one breaks away from established traditions creating room for discontinuous and new thinking and then reformulating one’s (art-)historical narratives and genealogies both in an intellectual way but also in terms of personal relations.

At kunsthalle wien, Oscar Murillo’s large-scale black canvases—a recurring element—fully develop their impressive architectural dimension. Suspended from the ceiling to create an almost labyrinthine structure, they carefully shape the space, allowing for intimate encounters with the works. While their intense darkness may elicit a sense of danger or perhaps mourning, this darkness can also be a space that breeds new life and rebirth.

Within this maze, we encounter further works by Murillo, such as a completely new set of landscape paintings titled fields of spirits (2023).

Frequencies, one of Murillo’s collaborative projects, initiated in 2013, involves visiting schools around the world, fixing canvas onto the pupils’ desks, letting them freely draw on, graffiti, and mark them, until, several months later, the artist collects them. In the kunsthalle wien exhibition, excerpts from this collection are installed as a large-scale wallpaper. The prints magnify the unconscious and conscious marks to striking proportions, as well as provide the basis for the Telegram (2013–2023) series.

Working with fragments—made in different spaces and time periods, and moved from place to place only to be stitched together or reworked layer by layer—has long been at the core of Murillo’s work. It’s a practice that highlights the presence of the many hands and vastly different geographical contexts that permeate his paintings, sculptures, and performances.

Circling Murillo’s structure but also deeply embedded in it, we find Rene Matić’s contributions to the exhibition: four new commissions—two films, a photography series, and a sound piece—as well as an existing wall installation.

Matić’s starting point for their contribution to the JAZZ. exhibition is Vienna’s response to and “outrage” at Josephine Baker’s performance in the city in 1928. A few years earlier, Baker, a US-American, had emigrated to Paris, where she became extraordinarily successful as a dancer and singer. Her experience in Vienna breaks with the somewhat romanticized narrative of her relatively liberal reception in Europe, contrasting the harsh racialized context she experienced in her homeland. The Austrian reviews regard Baker as “a serious attack on the values of European culture”. In these articles, Baker becomes synonymous with Blackness, jazz, and low culture, while Vienna, and Europe, become synonymous with whiteness, the waltz, and high culture.

The outrage Baker sparked in Vienna was so strong that the Church felt compelled to intervene, with many sermons warning of her seductive performances. Throughout the city, churches loudly rang their bells to prevent ‘poor souls’ from sinning and offered atonement services to strengthen parishioners’ relation to the “holy and divine”.

It is against this incident that Matić develops the film works redacted and climax, the photo series (out of) place, and the sound work voice (all 2024). In redacted, we see the artist dancing in a black space with a single fixed spotlight. As they dance, their body moves in and out of the darkness, in and out of the spotlight, and therefore also in and out of our gaze. Matić draws on darkness as a means of occlusion and a strategy of removal that can signify both refusal and protection—a notion of essential value to bodies that are already by default exposed in their cultural and societal context.

The filmic text work climax puts original quotations from Baker into direct dialogue with the Viennese reviews. This dialogue could be understood as a conversation, an argument, or maybe even lovemaking—or, as the artist says, a “hate-fuck”.

The photographic series occupies light boxes similar to those found across Vienna, including in MuseumsQuartier, the frames are a reference to Baker’s original performance advertisements. While the singer and dancer consciously reinforced the attraction and fantasies she elicited, Matić’s imagery too plays with certain eroticism, whilst also capturing an in-between moment of movement and intimacy, as if avoiding clear definition and rather allowing for a new space to open up.

In voice, the sound of church bells rings out within the gallery space from time to time—only in this case they do not signal a warning about but rather call for prayer for Baker, giving voice back to the dancer. The bell also acts as an interruption in the space, to remind the audience of their participation in the act of looking, and the histories and politics surrounding that act.

While both Matić and Murillo are generous in sharing their thinking, feeling, and practices, each also remains committed to “the right to opacity for everyone”. As the philosopher and poet Édouard Glissant argues in his book Poetics of Relation, transparency—through its attempts at definition and clarification—ignores the aspects of the self that are difficult to grasp, or even unknowable. Opacity, by contrast, simply accepts that everything that makes us us cannot be understood completely.

Curators What, How & for Whom / WHW and Laura Amann

For JAZZ. both artists present existing works as well as new commissions made specifically in response to the space and the city of Vienna. Encompassing painterly gestures, installation, film, photography, and sound, each element on show is in dialogue, shaped by Murillo’s black canvas installation which is suspended from the ceiling throughout the space.

Together, through dissection and reconciliation, both artists explore the impossibilities and contradictions that arise from notions of desire, visibility, and opacity.

Coming from differing vantage points and mediums, both artists employ gesture and abstraction within their practices. Murillo chooses the social over the subjective and the collective over the individual, while Matić’s practice is often grounded in the personal. Murillo’s works, and even titles, often reference the act of sending messages or of recording, intercepting, and tuning into, while Matić displays a deep concern with the reception of the image. Murillo’s paintings and drawings come to life through mark-making and gesture; Matić’s works use dance as a form of expression within the realm of the moving image and photography. In this sense, JAZZ.—a title that evokes many resonances and qualities within each artist’s practice—could be understood as a mode of artistic collaboration but also of reception: one where cultural sensibilities are blended, improvisation takes place and group interaction becomes as vital as the individual voice. JAZZ. nods to concepts of desire, of consumption of the Other, it plays with performativity while retaining the right to opacity.

While in some ways the practices of Matić and Murillo seem rather complementary to one another, they also overlap in important aspects. For instance, the gestural painting, reminiscent of action painting, that is so often at the heart of Murillo’s work is akin to the use of dance and dancing in Matić’s videos, as they both share a spontaneous, unbothered, and unscripted nature. Both artists also share intuition within their process and production, a calculated intuition. One could say intuition deployed strategically. Additionally, both artists succeed in carving out a space of independence for themselves in a cultural context that is determined to classify and smooth out everything and everyone. Claiming such a space first entails an act of “disaffiliation” (concept by Édouard Glissant), through which one breaks away from established traditions creating room for discontinuous and new thinking and then reformulating one’s (art-)historical narratives and genealogies both in an intellectual way but also in terms of personal relations.

At kunsthalle wien, Oscar Murillo’s large-scale black canvases—a recurring element—fully develop their impressive architectural dimension. Suspended from the ceiling to create an almost labyrinthine structure, they carefully shape the space, allowing for intimate encounters with the works. While their intense darkness may elicit a sense of danger or perhaps mourning, this darkness can also be a space that breeds new life and rebirth.

Within this maze, we encounter further works by Murillo, such as a completely new set of landscape paintings titled fields of spirits (2023).

Frequencies, one of Murillo’s collaborative projects, initiated in 2013, involves visiting schools around the world, fixing canvas onto the pupils’ desks, letting them freely draw on, graffiti, and mark them, until, several months later, the artist collects them. In the kunsthalle wien exhibition, excerpts from this collection are installed as a large-scale wallpaper. The prints magnify the unconscious and conscious marks to striking proportions, as well as provide the basis for the Telegram (2013–2023) series.

Working with fragments—made in different spaces and time periods, and moved from place to place only to be stitched together or reworked layer by layer—has long been at the core of Murillo’s work. It’s a practice that highlights the presence of the many hands and vastly different geographical contexts that permeate his paintings, sculptures, and performances.

Circling Murillo’s structure but also deeply embedded in it, we find Rene Matić’s contributions to the exhibition: four new commissions—two films, a photography series, and a sound piece—as well as an existing wall installation.

Matić’s starting point for their contribution to the JAZZ. exhibition is Vienna’s response to and “outrage” at Josephine Baker’s performance in the city in 1928. A few years earlier, Baker, a US-American, had emigrated to Paris, where she became extraordinarily successful as a dancer and singer. Her experience in Vienna breaks with the somewhat romanticized narrative of her relatively liberal reception in Europe, contrasting the harsh racialized context she experienced in her homeland. The Austrian reviews regard Baker as “a serious attack on the values of European culture”. In these articles, Baker becomes synonymous with Blackness, jazz, and low culture, while Vienna, and Europe, become synonymous with whiteness, the waltz, and high culture.

The outrage Baker sparked in Vienna was so strong that the Church felt compelled to intervene, with many sermons warning of her seductive performances. Throughout the city, churches loudly rang their bells to prevent ‘poor souls’ from sinning and offered atonement services to strengthen parishioners’ relation to the “holy and divine”.

It is against this incident that Matić develops the film works redacted and climax, the photo series (out of) place, and the sound work voice (all 2024). In redacted, we see the artist dancing in a black space with a single fixed spotlight. As they dance, their body moves in and out of the darkness, in and out of the spotlight, and therefore also in and out of our gaze. Matić draws on darkness as a means of occlusion and a strategy of removal that can signify both refusal and protection—a notion of essential value to bodies that are already by default exposed in their cultural and societal context.

The filmic text work climax puts original quotations from Baker into direct dialogue with the Viennese reviews. This dialogue could be understood as a conversation, an argument, or maybe even lovemaking—or, as the artist says, a “hate-fuck”.

The photographic series occupies light boxes similar to those found across Vienna, including in MuseumsQuartier, the frames are a reference to Baker’s original performance advertisements. While the singer and dancer consciously reinforced the attraction and fantasies she elicited, Matić’s imagery too plays with certain eroticism, whilst also capturing an in-between moment of movement and intimacy, as if avoiding clear definition and rather allowing for a new space to open up.

In voice, the sound of church bells rings out within the gallery space from time to time—only in this case they do not signal a warning about but rather call for prayer for Baker, giving voice back to the dancer. The bell also acts as an interruption in the space, to remind the audience of their participation in the act of looking, and the histories and politics surrounding that act.

While both Matić and Murillo are generous in sharing their thinking, feeling, and practices, each also remains committed to “the right to opacity for everyone”. As the philosopher and poet Édouard Glissant argues in his book Poetics of Relation, transparency—through its attempts at definition and clarification—ignores the aspects of the self that are difficult to grasp, or even unknowable. Opacity, by contrast, simply accepts that everything that makes us us cannot be understood completely.

Curators What, How & for Whom / WHW and Laura Amann