Elene Chantladze

As in a Melody or a Bird’s Nest

07 Oct 2023 - 28 Jan 2024

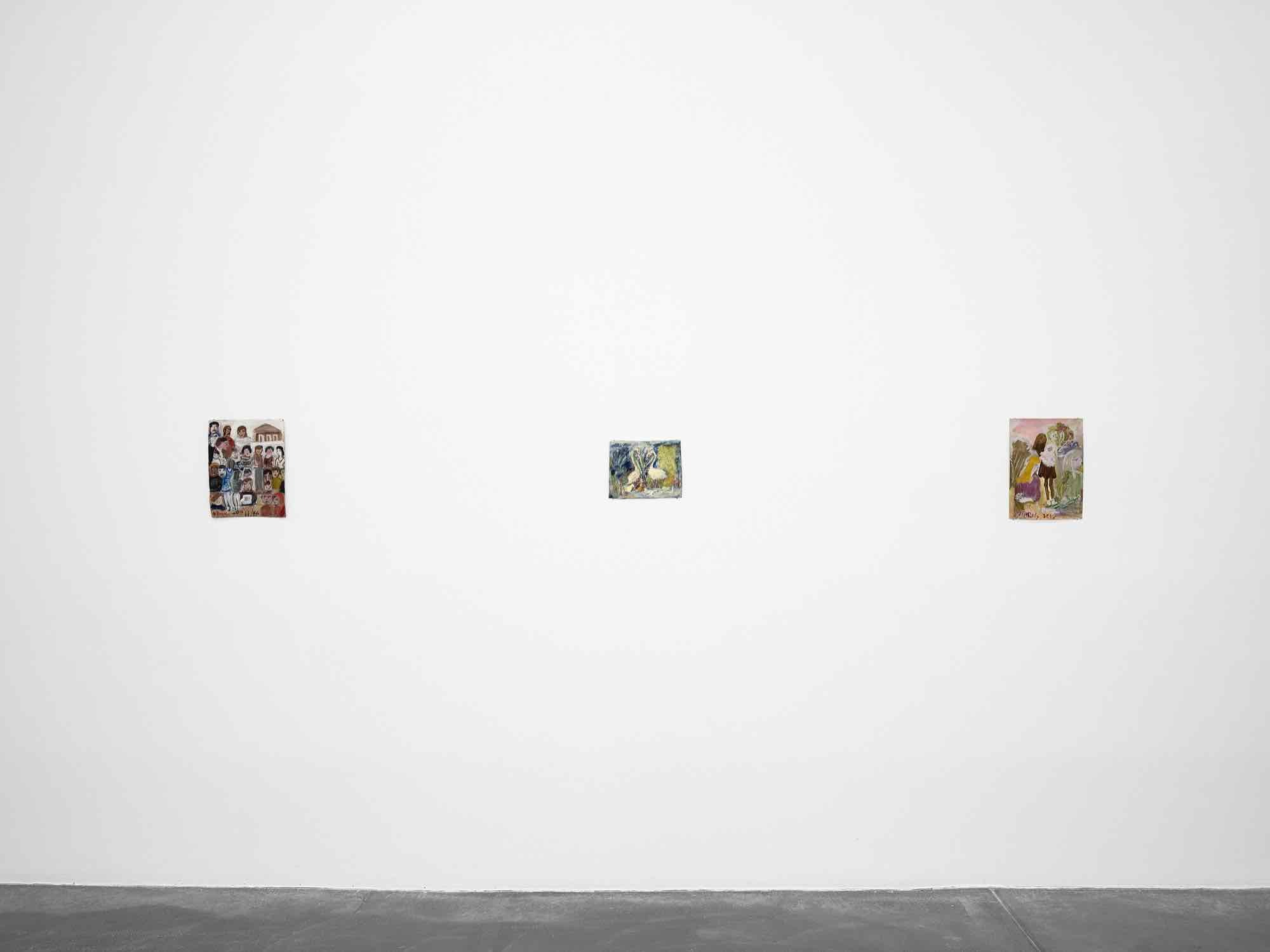

‘თავისუფალი ხატვა’ translates as ‘free drawing’. The Georgian artist Elene Chantladze employs this term to title many of her works, at times painted into the picture, defining her manner of painting. Writing is not infrequently a pictorial element; the artist worked as a poet and author for a significant period prior to painting. Signature, date or an image description appear in the pictures sometimes as prominently as the figures depicted. Her term of free drawing perfectly characterises her approach to the medium, for every line, every figurative gesture and every compositional decision is generated from the process of painting itself. All of her works are created on and with the materials that she has immediately to hand. As well as coloured pencils, gouache and ballpoint pen, coffee, the juice of pressed fruit or grease also all come into play. The cardboard from a box of chocolates, pages of a calendar or, for example, the back of a cupboard provide image carriers for paintings. Depending on the qualities of the material, Chantladze is either guided directly by the given structure of the surface or, with fast brushstrokes, generates an abstract painterly texture which defines the conception of the image. Thus, she initially creates a suggestive layer without representational intentions, which relies to no small extent on chance and brings creative action itself – without compositional forethought – into focus.

Building on this first stage, Chantladze develops her pictorial programme: she draws associations from the streaks and abstract forms of her relatively haphazardly created ground, conjuring faces, figures, plants and landscapes. In order to fix her visions, she paints over some areas of the image ground, highlights certain shapes, carves thin strokes into the wet paint and develops pen outlines around other silhouettes. A final layer of white along the contours, creating more homogeneous areas between the figures, often then clarifies the pictorial action. What results are concentrated scenes that swing between abstraction and figuration: sometimes individual figures seem to emerge from a diffuse background, sometimes a complete gathering of figures dominates the image and entirely covers the initial layer of painting. The pictures are composed either of distant, almost isolated characters, or densely populated scenes – sometimes so tight that the figures come together like puzzle pieces, the edges of one figure defining the form of their neighbour. As in icon painting, the figures seem to float auratically and most of the time frontally in a vaguely defined pictorial space tilted theatrically towards the viewer. These spaces only sometimes suggest a landscape or interior: a single table, chair or window draws the scene into a domestic setting; flowers, waves or a cluster of three trees work like stylised props in an otherwise mysterious location placing the action, with a reduced gesture, in a natural context. A hollowed-out rock formation locates another scene in the monastery of Dawid Gareja on the Georgian border with Azerbaijan, while framing structures like the carriage in the image კაცი რომელიც იცინის (The Man Who Laughs) (2019) demonstrate the role of community defining architectures. Here and there an animal or the suggestion of a face is to be found in the spaces between pictorial elements, where the outlines invite it.

Like her materials, the subjects of Chantladze’s work emerge from her immediate surroundings. They often come from a family context, village life or folklore; some images deal with political and historic events in Georgia, while others quote popular culture and show characters from novels, theatre or film. Female figures in particular appear repeatedly, sometimes with lowered eyes, turning away in sad isolation, sometimes in an intimate relationship with others or demonstrating tender affection towards children and animals, as wishful notions about loving togetherness. Chantladze always directs her attention towards people or animals, in her own words “only earthly creatures”, with all their perhaps mundane yet complex interrelations.

Given the artist’s devotion to all kinds of creatures and her painterly approach, it would be apt to compare her to certain Surrealists and their automatic painting techniques. Yet despite the apparently random nature of her work, Chantladze’s pictorial approach is not arbitrary or metaphysical, but closely tied to reality and her own environment. Convincing art historical links can, if needed, be made in further directions: from Eastern Orthodox icon painting to Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani or Soviet film. What is more, the material she uses can be read in relation to theoretical discourses on the distribution of goods and advertising aesthetics, as well as accessibility, improvisation and agency. She negotiates social as she does literary and personal themes; the Russian military’s invasion of South Ossetia in 2008, for example, she views with uncomprehending horror, yet with the same poetic realism that one feels in her paintings of tragic plays and in family portraits.

Chantladze’s work is not defined by a rigorous approach to the medium, but is marked by an earnestness that is particularly noticeable for its continuity. In the entire period of her artistic work there is no search for style, there are no phases of discovery. Her confidence when drawing out images – Chantladze’s trust in the painterly process and in her direct influences – is noticeable in all her paintings. They are images of a life with art, far away from major centres, but with a close connection to the here and now. Her works are being shown for the first time in an institutional solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Zürich.

Curated by v, assistant curator Kunsthalle Zürich

Building on this first stage, Chantladze develops her pictorial programme: she draws associations from the streaks and abstract forms of her relatively haphazardly created ground, conjuring faces, figures, plants and landscapes. In order to fix her visions, she paints over some areas of the image ground, highlights certain shapes, carves thin strokes into the wet paint and develops pen outlines around other silhouettes. A final layer of white along the contours, creating more homogeneous areas between the figures, often then clarifies the pictorial action. What results are concentrated scenes that swing between abstraction and figuration: sometimes individual figures seem to emerge from a diffuse background, sometimes a complete gathering of figures dominates the image and entirely covers the initial layer of painting. The pictures are composed either of distant, almost isolated characters, or densely populated scenes – sometimes so tight that the figures come together like puzzle pieces, the edges of one figure defining the form of their neighbour. As in icon painting, the figures seem to float auratically and most of the time frontally in a vaguely defined pictorial space tilted theatrically towards the viewer. These spaces only sometimes suggest a landscape or interior: a single table, chair or window draws the scene into a domestic setting; flowers, waves or a cluster of three trees work like stylised props in an otherwise mysterious location placing the action, with a reduced gesture, in a natural context. A hollowed-out rock formation locates another scene in the monastery of Dawid Gareja on the Georgian border with Azerbaijan, while framing structures like the carriage in the image კაცი რომელიც იცინის (The Man Who Laughs) (2019) demonstrate the role of community defining architectures. Here and there an animal or the suggestion of a face is to be found in the spaces between pictorial elements, where the outlines invite it.

Like her materials, the subjects of Chantladze’s work emerge from her immediate surroundings. They often come from a family context, village life or folklore; some images deal with political and historic events in Georgia, while others quote popular culture and show characters from novels, theatre or film. Female figures in particular appear repeatedly, sometimes with lowered eyes, turning away in sad isolation, sometimes in an intimate relationship with others or demonstrating tender affection towards children and animals, as wishful notions about loving togetherness. Chantladze always directs her attention towards people or animals, in her own words “only earthly creatures”, with all their perhaps mundane yet complex interrelations.

Given the artist’s devotion to all kinds of creatures and her painterly approach, it would be apt to compare her to certain Surrealists and their automatic painting techniques. Yet despite the apparently random nature of her work, Chantladze’s pictorial approach is not arbitrary or metaphysical, but closely tied to reality and her own environment. Convincing art historical links can, if needed, be made in further directions: from Eastern Orthodox icon painting to Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani or Soviet film. What is more, the material she uses can be read in relation to theoretical discourses on the distribution of goods and advertising aesthetics, as well as accessibility, improvisation and agency. She negotiates social as she does literary and personal themes; the Russian military’s invasion of South Ossetia in 2008, for example, she views with uncomprehending horror, yet with the same poetic realism that one feels in her paintings of tragic plays and in family portraits.

Chantladze’s work is not defined by a rigorous approach to the medium, but is marked by an earnestness that is particularly noticeable for its continuity. In the entire period of her artistic work there is no search for style, there are no phases of discovery. Her confidence when drawing out images – Chantladze’s trust in the painterly process and in her direct influences – is noticeable in all her paintings. They are images of a life with art, far away from major centres, but with a close connection to the here and now. Her works are being shown for the first time in an institutional solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Zürich.

Curated by v, assistant curator Kunsthalle Zürich