Pippa Garner

Act Like You Know Me

04 Feb - 14 May 2023

Kunsthalle Zürich presents the first comprehensive solo exhibition of the artist Pippa Garner in Europe, which offers a necessarily fragmentary insight into an incredibly extensive body of work spanning more than 50 years. The exhibition is co-curated by Fiona Alison Duncan, New-York based author, Maurin Dietrich, Director Kunstverein Munich, and Daniel Baumann, Kunsthalle Zürich, in collaboration with Otto Bonnen, assistant curator Kunsthalle Zürich, and Miriam Laura Leonardi, artist. The exhibition in Zürich takes on and expands the exhibition on show at Kunstverein Munich in 2022.

Born in 1942 in the Chicago suburb of Evanston, Illinois, the U.S.-American artist and author formerly known as Philip Garner pushes back against systems of consumerism, marketing and waste and has created a dense body of work including drawing, performance, sculpture, video and installation over her five decade-spanning career.(1) Her uncompromising approach to life and practice has allowed her to interact with the worlds of illustration, editorial, television and art without ever quite becoming beholden to them.

The beginning of Garner’s public practice can be traced to her time serving as a U.S. Army Combat Artist in the Vietnam War and the years that directly followed. Drafted while working on an assembly line at a car plant, Garner was flown to Vietnam in 1966 with a foot soldier assignment, as the United States was escalating its presence overseas, enforcing an enlistment of thousands of young Americans per month. By chance, Garner was assigned to the 25th Infantry, the only division with a Combat Art Team (CAT). Learning of this program – which charged soldier and civilian artists with documenting the war in the forms of sketches, illustrations, and paintings to be collected by the U.S. Army for (in their words) ‘the annals of military history –’ Garner negotiated a position on the CAT team. This assignment would save her from having to engage in direct combat, if not from the trauma of war (in 2010, Garner was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, a cancer caused by exposure to the chemical defoliant ‘Agent Orange’). Garner bided her time abroad by practicing a new, to her, art form: photography. Using cutting-edge Japanese cameras she had purchased in Saigon, Garner started taking personal photographs at every possible juncture. These images exhibit obsessions with subjects that would preoccupy Garner throughout the rest of her life and career, among them transport vehicles, architecture and urban design, candid street scenes, humorous street signs, satirical and sensual selfportraits, gender bending fashion and pets and animals.

After returning to the United States, Garner resumed her studies in the highly regarded Transportation Design department at ArtCenter, California, with plans to become a car stylist, but was swiftly expelled when, in 1969, she presented her year-end project, Kar-Mann (Half Human Half Car), a centaur-like sculpture featuring the front body of a slick silver automobile with the lower half of a nude human whose limbs are lifted like a dog mid-urination. Smooth and pale, the nude might be assumed to represent a cis female were it not for its attentively rendered penis and scrotum. Like most of Garner’s art objects – the hundreds of sculptures, wall works, design objects and garments she made between the late 1960s and the early 2010s – Kar-Mann (Half Human Half Car) was not professionally archived nor was it collected. Last seen by the artist in the 1970s, with the final outcome of the object unknown, what remains of Garner’s first intentional artwork are photographs, staged and shot by the artist herself.

Photography was Garner’s entry into a public, if ambiguously commercial, art practice. Following her expulsion from ArtCenter, Garner stayed in Los Angeles, working at a toy design firm. In her spare time, she biked around the sprawling city, taking photographs. Garner’s street scenes rarely have people in them. What we see, rather, are amusing DIY design choices and human design failures, including cars in states of deterioration or wild customisation as well as provocative and humorous bumper stickers and business signs. Upon seeing her portfolio, a colleague at the toy design firm suggested that Garner bring her photographs to the Los Angeles Times’ new Sunday supplement, West, a progressive magazine known for its art direction. West immediately started publishing Garner’s work, setting her on a course that would last until the early 21st century, when the internet subsumed advertising budgets previously allocated to print magazines and thus print’s ability to pay contributors a living wage.

Garner’s work for magazines – ranging from Esquire, Rolling Stone, Vogue, Playboy and Wet to Car & Driver and Arts & Architecture – have an interesting, shifting status as art. Initially published in the commercial venue of a popular magazine, the photographs, illustrations, performances and sculptures made for these pages were conceptually driven and fabricated by the artist’s hand with little to no editorial intervention. Never selling anything, but rather deconstructing the very idea of selling through satirical reflections on consumerism and contemporary American life, the work’s commercial placement alone precluded it, as Garner understood it, from being considered seriously in its day as art. “There was such a line of demarcation,” Garner explains, “between anything commercial and fine arts.” Garner was disappointed by this bias but more excited by a mass audience: “It became an obsession,” she recalls, “to put things in print and get thousands and thousands of people to see it.”

One of Garner’s most significant works, the Backwards Car, 1974, was facilitated by Esquire, which agreed to pay for a used Chevrolet, the body of which was removed from its chassis by Garner – who did all of the mechanical work herself – then flipped around and refastened, so the car appeared to be driving backwards when it was moving forwards and vice-versa. The most iconic photographs of the project show the accident-chancing automobile moving with traffic over San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge.

Stunts like the Backwards Car drew the attention of artists and the art world. Garner’s circle during the 1970s and early 1980s grew to include West Coast artists such as Ed Ruscha, Chris Burden, and the radical art and design collective Ant Farm, whom Garner would collaborate with. Another collaborator, the painter Nancy Reese, was a major influence. Trained in a fine art tradition, Reese – at once Garner’s creative and romantic partner – introduced her to contemporary art institutions and communities, as well as to the idea that Garner might identify as an artist herself.

Frequent collaborators, Reese modelled in many of Garner’s photographs while Reese painted her partner in turn. The couple were simultaneously exhibiting at the local level and in formidable institutions: together at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1980) and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (1984); separately at the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art (Garner in 1980, Reese in 1981); Garner at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (1984) and again the MOCA, Los Angeles (1985); and Reese at Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles (1986, 1987). Juggling high and low, Garner was also, at this time, enjoying mainstream attention as her inventive work in magazines evolved into three book deals: Philip Garner’s Better Living Catalog, 1982, Utopia or Bust: Products for the Perfect World, 1984, and Garner’s Gizmos & Gadgets, 1987. Promotion of these books segued into television appearances on talk shows, most notably the Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson to which Garner wore her famous Half-Suit, 1982.

Garner had started gender hacking in 1984 by privately dosing on black market oestrogen. She later described the decision as an ‘aha’ moment of inspiration: “In my earlier work,” she explains, “I was always using objects that were consumer goods, things that came off assembly lines. I remember looking in the mirror one day – this was in the ’80s – and I thought, ‘Hey, I’m an object, too. I’m just another appliance.’” Gender, as Garner saw it, was the cornerstone of consumer identity, while the body was a technology, not so different from a car; why not reverse her own anatomy, as she had with that 1959 Chevy?

‘The concept of sex-change as a form of consumer technology began to intrigue me,’ Garner wrote in a 1995 journal entry. That same year she posted a personal ad in a local San Francisco back page that read ‘Post-op (I did it for art).’ These confident statements were a long time coming. Garner’s ‘sex change,’ as she called it (using the vocabulary of the times), was actually a decade-long process propelled by curiosity, intuition and desire, a personal and cultural experiment conducted with the uncertainty and risk intrinsic to the scientific method. Only later would she rightly call it art.

Garner never felt ‘born in the wrong body.’ When she first began hormone therapy there was no widespread concept of the in-betweens of gender, and no good terms for people who lived there. As she puts it, “You had to jump over the fence.” And so she did – from one binary (as Phil, Garner had presented as hyper masculine) to another (for a handful of years, she tried living as a high femme), only to land somewhere in the middle; that is, removing ‘the fence’ altogether. We now have language for someone like Garner, terms such as nonbinary, genderqueer and transgender. (Garner likes the word transgender but prefers the ancient term androgyny over the more contemporary nonbinary.) Back in the 1980s and early 1990s, Garner’s approach to gender transition was often misunderstood, resulting in isolation from both old friends who missed ‘Phil’ and select LGBTQ+ community members who found Garner’s irreverent relationship to gender to be a mockery. Intelligent and entertaining, Garner was never short of allies, however. She continued to be employed by loyal editors as an illustrator for magazines, doing the back page of Los Angeles Magazine then Car & Driver. Having left Los Angeles for the more inclusive queer bastion of San Francisco and the Bay area, she expressed herself through personal ads and appearances in local newspapers and radio. She also documented every aspect of her transition in photography and writing, taking intimate selfportraits, journaling deeply and collecting legal documents by and correspondences with her therapists and surgeons (she considers her many procedures to be ‘collaborations’ with those doctors).

During this time, Garner’s relationship with cars went through a simultaneous transition. Always ambivalent – critical yet obsessed with cars – by 1990, her attachment was chinking away, exemplified by Protect the Innocent, a bright yellow 1960s Toyota from which she removed as much of the exterior body as she could safely (one of the few large-scale works of Garner’s to survive, Protect the Innocent is collected by the artist Paul McCarthy.) For her last gesture with an actual commercial car, Garner applied, in 1995, for the custom license plate SX CHNGE, a petition that was denied by the Department of Motor Vehicles who wrote ‘the plate configuration request… maybe [sic] considered by some of our citizens to be offensive or misleading.’ Garner resubmitted a request – which was approved – for the plate HE 2 SHE. These were art gestures though; in terms of personal use, cars had taken a back seat to pedal vehicles for Garner for a long time, and in the 1990s, she finally quit driving altogether. Denouncing the oil industry, wars abroad, suburban alienation and land waste, Garner also concluded that she simply preferred to self-propel, using her own body as engine and fuel.

While prolifically productive at a local and personal level, Garner’s professional art career was practically non-existent from 1986 to 2014. She only exhibited once, in 1997, as part of Hello Again!, a recycled art show at the Oakland Museum. Gender discrimination accounts, in part, for this temporary exile. Since Garner was never one to pursue institutional opportunities herself, it was up to curators and fellow artists to recognize Garner as belonging to the museum and gallery system. A confluence of cultural updates set the stage for Garner’s recent rediscovery, not only the dawning of a new, expansive queer and feminist consciousness, the Internet and social media also further flattened the distinctions between mediums and fields, resulting in a generation unperturbed by Garner’s eclectic transdisciplinary manifestations.

What the exhibition Act Like You Know Me proves is that Garner lived a life of constant, obsessive art making. Looking back, we can read Garner’s vast works as united under a cohesive conceptual practice, whether they first premiered in a magazine, a book or a local paper; on television; in a gallery or museum; in the streets; on her body; or nowhere but the privacy of Garner’s often solitary life. The idea that Garner is a conceptual artist is not new. In his 2006 book Full Moon, artist Paul Ruscha, Ed Ruscha’s brother, reflects on the 1980s Los Angeles art world, writing that Garner ‘was regarded by all as the mad genius of conceptual art.’ While previous exhibitions have tended to focus on the materiality of Garner’s satirical consumer propositions and her persona as ‘an inventor’ or ‘absurdist’– to reduce her to roles she had performed while engaging with 20th century publishing and commercial art markets – Act Like You Know Me rather aims to position Garner in the tradition of conceptual art. “Inventor,” as she has confided to writer and the co-curator of this exhibition Fiona Alison Duncan, was a label and character she had played with that the media repeated as her truth, so she ran with it. ‘My behavior,’ the artist penned in one of her many notebooks, ‘is a reflection of the culture.’

The cyclical nature of the material world and the mystery of immateriality are the true bedrocks of Garner’s practice. This comes through in her reliance on found and recycled materials and in her habit of destroying, recycling and/or giving away what she has made. The Backwards Car was shredded. More often than not, she has refused financial compensation in the acquisition of her art. Even her ‘inventions’ – clever consumer goods she fabricated once as an object to be photographed or illustrated as a simple pitch – were never designed for mass-production. Published in catalogue form with no purchase forms, Garner’s products reflected the absurdity and the waste of overproduction and overconsumption; at the same time, Garner allowed herself and her audience to delight in ideation, perhaps the most pleasant stage of creation and consumption. The few covetable products Garner proposed tended to be those that a person could craft themselves, just as Garner had, for example, the Half-Suit and other fashion items, versions of which have turned up in high fashion collections since.

A look into Garner’s ascetic personal life and career indecision reveals a rigorous detachment from bourgeois comforts, binary gender included. Her androgyny-centred transition emerges as but another manifestation of her experimental attitude, transpersonal identity, prankish sense of humour and deep connection to the transitory nature of material life. Fluidity and flux shape Garner’s practice of altering materials of mass production, and that includes mass produced synthetic hormones, plastic surgery and cosmetics. Whatever satire on gender Garner’s multiple performances of the self serve, they do not negate the experiential realities of sexuality and gender identity but find pleasure rather in their multiplicity and in the power of self-determination, while playfully calling out class bias: how gender is often packaged as desirable through its association with wealth and power. ‘I’d be more beautiful,’ one of her earliest slogan t-shirts reads, ‘but I ran out of money.’

Playing in and with the refuse of capitalism, from the disposable print matter of magazines to thrifted t-shirts, Garner’s personal and art-vocational choices are, without abandoning society altogether, remarkably sustainable. More than sustainable in the last two decades: biking and making art mostly from scraps, it’s as if she has been living after the climate apocalypse or in a culture determined to prevent it. This is the California counterculture hippie ethic carried into the 21st century, an ethic that most people of Garner’s demographic abandoned a long time ago in favour of complicity with financial and consumer capitalism.

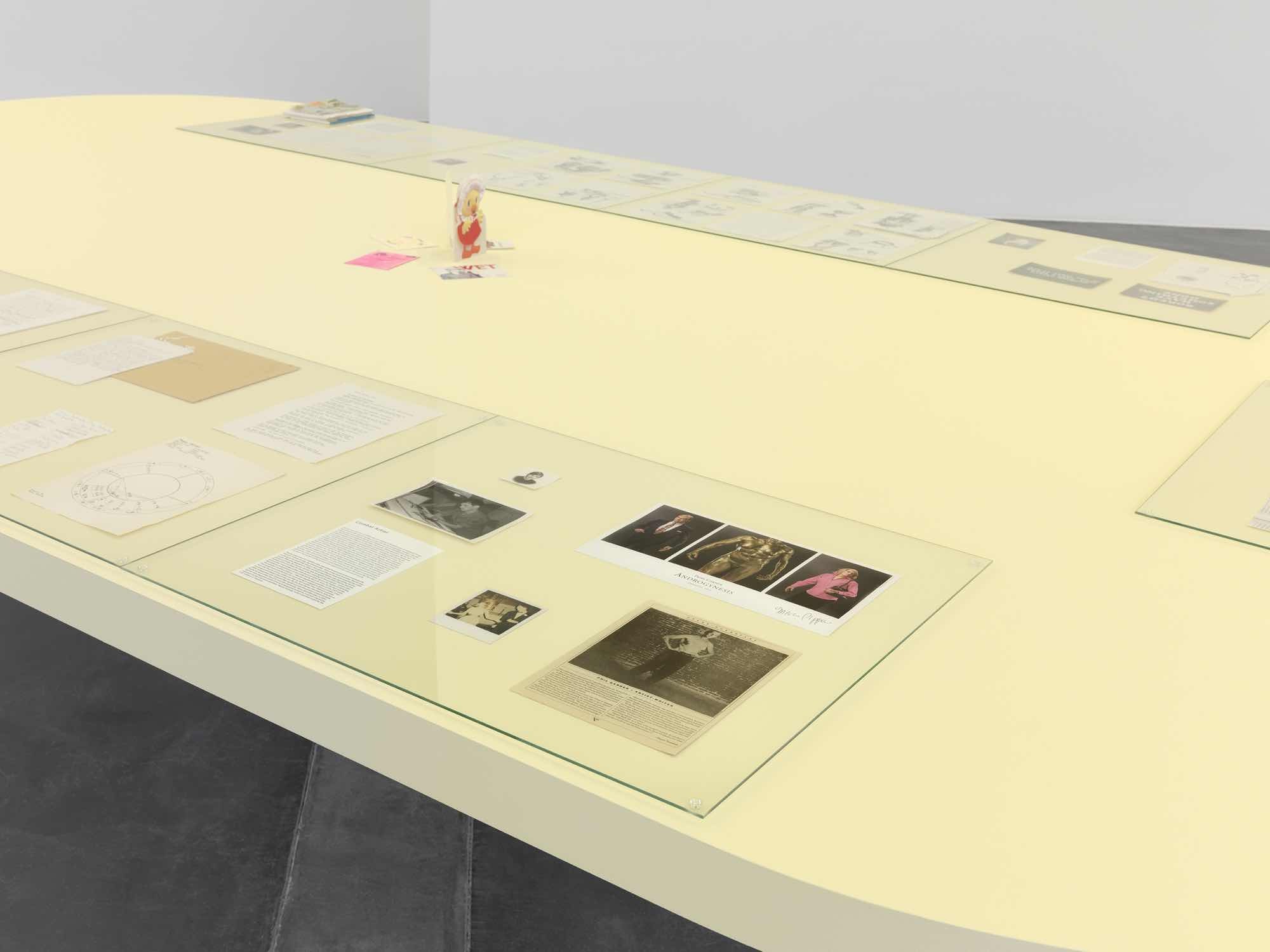

Thankfully, for all her anti-materialist persuasion, Garner had enough of an attachment to the world to maintain an archive of her life’s work in the forms of photographic slides, drawings, select garments and ephemera. It is these materials that make up the exhibition Act Like You Know Me, a survey of Garner’s practice from the late 1960s to the early 2000s with a focus on the artist’s wild, extensive photographs that both have the status of autonomous works as well as documentation of her practice.

Text: Fiona Alison Duncan

The exhibition is co-curated by Fiona Alison Duncan, New York-based writer, Maurin Dietrich, Kunstverein München, and Daniel Baumann, Kunsthalle Zürich, in collaboration with Otto Bonnen, assistant curator Kunsthalle Zürich, and artist Miriam Laura Leonardi.

The exhibition is a takeover and extension of the exhibition shown at the Kunstverein München in 2022. Other aspects of Garner's work will be on view in an exhibition at FRAC Lorraine, Metz, which runs in parallel with the Kunsthalle Zürich presentation from 17 February-20 August 2023. Pippa Garner’s exhibition is accompanied by an extensive mediation programme, including schools workshops and free exhibition tours every Thursday.

Born in 1942 in the Chicago suburb of Evanston, Illinois, the U.S.-American artist and author formerly known as Philip Garner pushes back against systems of consumerism, marketing and waste and has created a dense body of work including drawing, performance, sculpture, video and installation over her five decade-spanning career.(1) Her uncompromising approach to life and practice has allowed her to interact with the worlds of illustration, editorial, television and art without ever quite becoming beholden to them.

The beginning of Garner’s public practice can be traced to her time serving as a U.S. Army Combat Artist in the Vietnam War and the years that directly followed. Drafted while working on an assembly line at a car plant, Garner was flown to Vietnam in 1966 with a foot soldier assignment, as the United States was escalating its presence overseas, enforcing an enlistment of thousands of young Americans per month. By chance, Garner was assigned to the 25th Infantry, the only division with a Combat Art Team (CAT). Learning of this program – which charged soldier and civilian artists with documenting the war in the forms of sketches, illustrations, and paintings to be collected by the U.S. Army for (in their words) ‘the annals of military history –’ Garner negotiated a position on the CAT team. This assignment would save her from having to engage in direct combat, if not from the trauma of war (in 2010, Garner was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, a cancer caused by exposure to the chemical defoliant ‘Agent Orange’). Garner bided her time abroad by practicing a new, to her, art form: photography. Using cutting-edge Japanese cameras she had purchased in Saigon, Garner started taking personal photographs at every possible juncture. These images exhibit obsessions with subjects that would preoccupy Garner throughout the rest of her life and career, among them transport vehicles, architecture and urban design, candid street scenes, humorous street signs, satirical and sensual selfportraits, gender bending fashion and pets and animals.

After returning to the United States, Garner resumed her studies in the highly regarded Transportation Design department at ArtCenter, California, with plans to become a car stylist, but was swiftly expelled when, in 1969, she presented her year-end project, Kar-Mann (Half Human Half Car), a centaur-like sculpture featuring the front body of a slick silver automobile with the lower half of a nude human whose limbs are lifted like a dog mid-urination. Smooth and pale, the nude might be assumed to represent a cis female were it not for its attentively rendered penis and scrotum. Like most of Garner’s art objects – the hundreds of sculptures, wall works, design objects and garments she made between the late 1960s and the early 2010s – Kar-Mann (Half Human Half Car) was not professionally archived nor was it collected. Last seen by the artist in the 1970s, with the final outcome of the object unknown, what remains of Garner’s first intentional artwork are photographs, staged and shot by the artist herself.

Photography was Garner’s entry into a public, if ambiguously commercial, art practice. Following her expulsion from ArtCenter, Garner stayed in Los Angeles, working at a toy design firm. In her spare time, she biked around the sprawling city, taking photographs. Garner’s street scenes rarely have people in them. What we see, rather, are amusing DIY design choices and human design failures, including cars in states of deterioration or wild customisation as well as provocative and humorous bumper stickers and business signs. Upon seeing her portfolio, a colleague at the toy design firm suggested that Garner bring her photographs to the Los Angeles Times’ new Sunday supplement, West, a progressive magazine known for its art direction. West immediately started publishing Garner’s work, setting her on a course that would last until the early 21st century, when the internet subsumed advertising budgets previously allocated to print magazines and thus print’s ability to pay contributors a living wage.

Garner’s work for magazines – ranging from Esquire, Rolling Stone, Vogue, Playboy and Wet to Car & Driver and Arts & Architecture – have an interesting, shifting status as art. Initially published in the commercial venue of a popular magazine, the photographs, illustrations, performances and sculptures made for these pages were conceptually driven and fabricated by the artist’s hand with little to no editorial intervention. Never selling anything, but rather deconstructing the very idea of selling through satirical reflections on consumerism and contemporary American life, the work’s commercial placement alone precluded it, as Garner understood it, from being considered seriously in its day as art. “There was such a line of demarcation,” Garner explains, “between anything commercial and fine arts.” Garner was disappointed by this bias but more excited by a mass audience: “It became an obsession,” she recalls, “to put things in print and get thousands and thousands of people to see it.”

One of Garner’s most significant works, the Backwards Car, 1974, was facilitated by Esquire, which agreed to pay for a used Chevrolet, the body of which was removed from its chassis by Garner – who did all of the mechanical work herself – then flipped around and refastened, so the car appeared to be driving backwards when it was moving forwards and vice-versa. The most iconic photographs of the project show the accident-chancing automobile moving with traffic over San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge.

Stunts like the Backwards Car drew the attention of artists and the art world. Garner’s circle during the 1970s and early 1980s grew to include West Coast artists such as Ed Ruscha, Chris Burden, and the radical art and design collective Ant Farm, whom Garner would collaborate with. Another collaborator, the painter Nancy Reese, was a major influence. Trained in a fine art tradition, Reese – at once Garner’s creative and romantic partner – introduced her to contemporary art institutions and communities, as well as to the idea that Garner might identify as an artist herself.

Frequent collaborators, Reese modelled in many of Garner’s photographs while Reese painted her partner in turn. The couple were simultaneously exhibiting at the local level and in formidable institutions: together at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1980) and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (1984); separately at the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art (Garner in 1980, Reese in 1981); Garner at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (1984) and again the MOCA, Los Angeles (1985); and Reese at Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles (1986, 1987). Juggling high and low, Garner was also, at this time, enjoying mainstream attention as her inventive work in magazines evolved into three book deals: Philip Garner’s Better Living Catalog, 1982, Utopia or Bust: Products for the Perfect World, 1984, and Garner’s Gizmos & Gadgets, 1987. Promotion of these books segued into television appearances on talk shows, most notably the Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson to which Garner wore her famous Half-Suit, 1982.

Garner had started gender hacking in 1984 by privately dosing on black market oestrogen. She later described the decision as an ‘aha’ moment of inspiration: “In my earlier work,” she explains, “I was always using objects that were consumer goods, things that came off assembly lines. I remember looking in the mirror one day – this was in the ’80s – and I thought, ‘Hey, I’m an object, too. I’m just another appliance.’” Gender, as Garner saw it, was the cornerstone of consumer identity, while the body was a technology, not so different from a car; why not reverse her own anatomy, as she had with that 1959 Chevy?

‘The concept of sex-change as a form of consumer technology began to intrigue me,’ Garner wrote in a 1995 journal entry. That same year she posted a personal ad in a local San Francisco back page that read ‘Post-op (I did it for art).’ These confident statements were a long time coming. Garner’s ‘sex change,’ as she called it (using the vocabulary of the times), was actually a decade-long process propelled by curiosity, intuition and desire, a personal and cultural experiment conducted with the uncertainty and risk intrinsic to the scientific method. Only later would she rightly call it art.

Garner never felt ‘born in the wrong body.’ When she first began hormone therapy there was no widespread concept of the in-betweens of gender, and no good terms for people who lived there. As she puts it, “You had to jump over the fence.” And so she did – from one binary (as Phil, Garner had presented as hyper masculine) to another (for a handful of years, she tried living as a high femme), only to land somewhere in the middle; that is, removing ‘the fence’ altogether. We now have language for someone like Garner, terms such as nonbinary, genderqueer and transgender. (Garner likes the word transgender but prefers the ancient term androgyny over the more contemporary nonbinary.) Back in the 1980s and early 1990s, Garner’s approach to gender transition was often misunderstood, resulting in isolation from both old friends who missed ‘Phil’ and select LGBTQ+ community members who found Garner’s irreverent relationship to gender to be a mockery. Intelligent and entertaining, Garner was never short of allies, however. She continued to be employed by loyal editors as an illustrator for magazines, doing the back page of Los Angeles Magazine then Car & Driver. Having left Los Angeles for the more inclusive queer bastion of San Francisco and the Bay area, she expressed herself through personal ads and appearances in local newspapers and radio. She also documented every aspect of her transition in photography and writing, taking intimate selfportraits, journaling deeply and collecting legal documents by and correspondences with her therapists and surgeons (she considers her many procedures to be ‘collaborations’ with those doctors).

During this time, Garner’s relationship with cars went through a simultaneous transition. Always ambivalent – critical yet obsessed with cars – by 1990, her attachment was chinking away, exemplified by Protect the Innocent, a bright yellow 1960s Toyota from which she removed as much of the exterior body as she could safely (one of the few large-scale works of Garner’s to survive, Protect the Innocent is collected by the artist Paul McCarthy.) For her last gesture with an actual commercial car, Garner applied, in 1995, for the custom license plate SX CHNGE, a petition that was denied by the Department of Motor Vehicles who wrote ‘the plate configuration request… maybe [sic] considered by some of our citizens to be offensive or misleading.’ Garner resubmitted a request – which was approved – for the plate HE 2 SHE. These were art gestures though; in terms of personal use, cars had taken a back seat to pedal vehicles for Garner for a long time, and in the 1990s, she finally quit driving altogether. Denouncing the oil industry, wars abroad, suburban alienation and land waste, Garner also concluded that she simply preferred to self-propel, using her own body as engine and fuel.

While prolifically productive at a local and personal level, Garner’s professional art career was practically non-existent from 1986 to 2014. She only exhibited once, in 1997, as part of Hello Again!, a recycled art show at the Oakland Museum. Gender discrimination accounts, in part, for this temporary exile. Since Garner was never one to pursue institutional opportunities herself, it was up to curators and fellow artists to recognize Garner as belonging to the museum and gallery system. A confluence of cultural updates set the stage for Garner’s recent rediscovery, not only the dawning of a new, expansive queer and feminist consciousness, the Internet and social media also further flattened the distinctions between mediums and fields, resulting in a generation unperturbed by Garner’s eclectic transdisciplinary manifestations.

What the exhibition Act Like You Know Me proves is that Garner lived a life of constant, obsessive art making. Looking back, we can read Garner’s vast works as united under a cohesive conceptual practice, whether they first premiered in a magazine, a book or a local paper; on television; in a gallery or museum; in the streets; on her body; or nowhere but the privacy of Garner’s often solitary life. The idea that Garner is a conceptual artist is not new. In his 2006 book Full Moon, artist Paul Ruscha, Ed Ruscha’s brother, reflects on the 1980s Los Angeles art world, writing that Garner ‘was regarded by all as the mad genius of conceptual art.’ While previous exhibitions have tended to focus on the materiality of Garner’s satirical consumer propositions and her persona as ‘an inventor’ or ‘absurdist’– to reduce her to roles she had performed while engaging with 20th century publishing and commercial art markets – Act Like You Know Me rather aims to position Garner in the tradition of conceptual art. “Inventor,” as she has confided to writer and the co-curator of this exhibition Fiona Alison Duncan, was a label and character she had played with that the media repeated as her truth, so she ran with it. ‘My behavior,’ the artist penned in one of her many notebooks, ‘is a reflection of the culture.’

The cyclical nature of the material world and the mystery of immateriality are the true bedrocks of Garner’s practice. This comes through in her reliance on found and recycled materials and in her habit of destroying, recycling and/or giving away what she has made. The Backwards Car was shredded. More often than not, she has refused financial compensation in the acquisition of her art. Even her ‘inventions’ – clever consumer goods she fabricated once as an object to be photographed or illustrated as a simple pitch – were never designed for mass-production. Published in catalogue form with no purchase forms, Garner’s products reflected the absurdity and the waste of overproduction and overconsumption; at the same time, Garner allowed herself and her audience to delight in ideation, perhaps the most pleasant stage of creation and consumption. The few covetable products Garner proposed tended to be those that a person could craft themselves, just as Garner had, for example, the Half-Suit and other fashion items, versions of which have turned up in high fashion collections since.

A look into Garner’s ascetic personal life and career indecision reveals a rigorous detachment from bourgeois comforts, binary gender included. Her androgyny-centred transition emerges as but another manifestation of her experimental attitude, transpersonal identity, prankish sense of humour and deep connection to the transitory nature of material life. Fluidity and flux shape Garner’s practice of altering materials of mass production, and that includes mass produced synthetic hormones, plastic surgery and cosmetics. Whatever satire on gender Garner’s multiple performances of the self serve, they do not negate the experiential realities of sexuality and gender identity but find pleasure rather in their multiplicity and in the power of self-determination, while playfully calling out class bias: how gender is often packaged as desirable through its association with wealth and power. ‘I’d be more beautiful,’ one of her earliest slogan t-shirts reads, ‘but I ran out of money.’

Playing in and with the refuse of capitalism, from the disposable print matter of magazines to thrifted t-shirts, Garner’s personal and art-vocational choices are, without abandoning society altogether, remarkably sustainable. More than sustainable in the last two decades: biking and making art mostly from scraps, it’s as if she has been living after the climate apocalypse or in a culture determined to prevent it. This is the California counterculture hippie ethic carried into the 21st century, an ethic that most people of Garner’s demographic abandoned a long time ago in favour of complicity with financial and consumer capitalism.

Thankfully, for all her anti-materialist persuasion, Garner had enough of an attachment to the world to maintain an archive of her life’s work in the forms of photographic slides, drawings, select garments and ephemera. It is these materials that make up the exhibition Act Like You Know Me, a survey of Garner’s practice from the late 1960s to the early 2000s with a focus on the artist’s wild, extensive photographs that both have the status of autonomous works as well as documentation of her practice.

Text: Fiona Alison Duncan

The exhibition is co-curated by Fiona Alison Duncan, New York-based writer, Maurin Dietrich, Kunstverein München, and Daniel Baumann, Kunsthalle Zürich, in collaboration with Otto Bonnen, assistant curator Kunsthalle Zürich, and artist Miriam Laura Leonardi.

The exhibition is a takeover and extension of the exhibition shown at the Kunstverein München in 2022. Other aspects of Garner's work will be on view in an exhibition at FRAC Lorraine, Metz, which runs in parallel with the Kunsthalle Zürich presentation from 17 February-20 August 2023. Pippa Garner’s exhibition is accompanied by an extensive mediation programme, including schools workshops and free exhibition tours every Thursday.