The Brotherhood of New Blockheads (1996–2002)

16 Feb - 26 May 2019

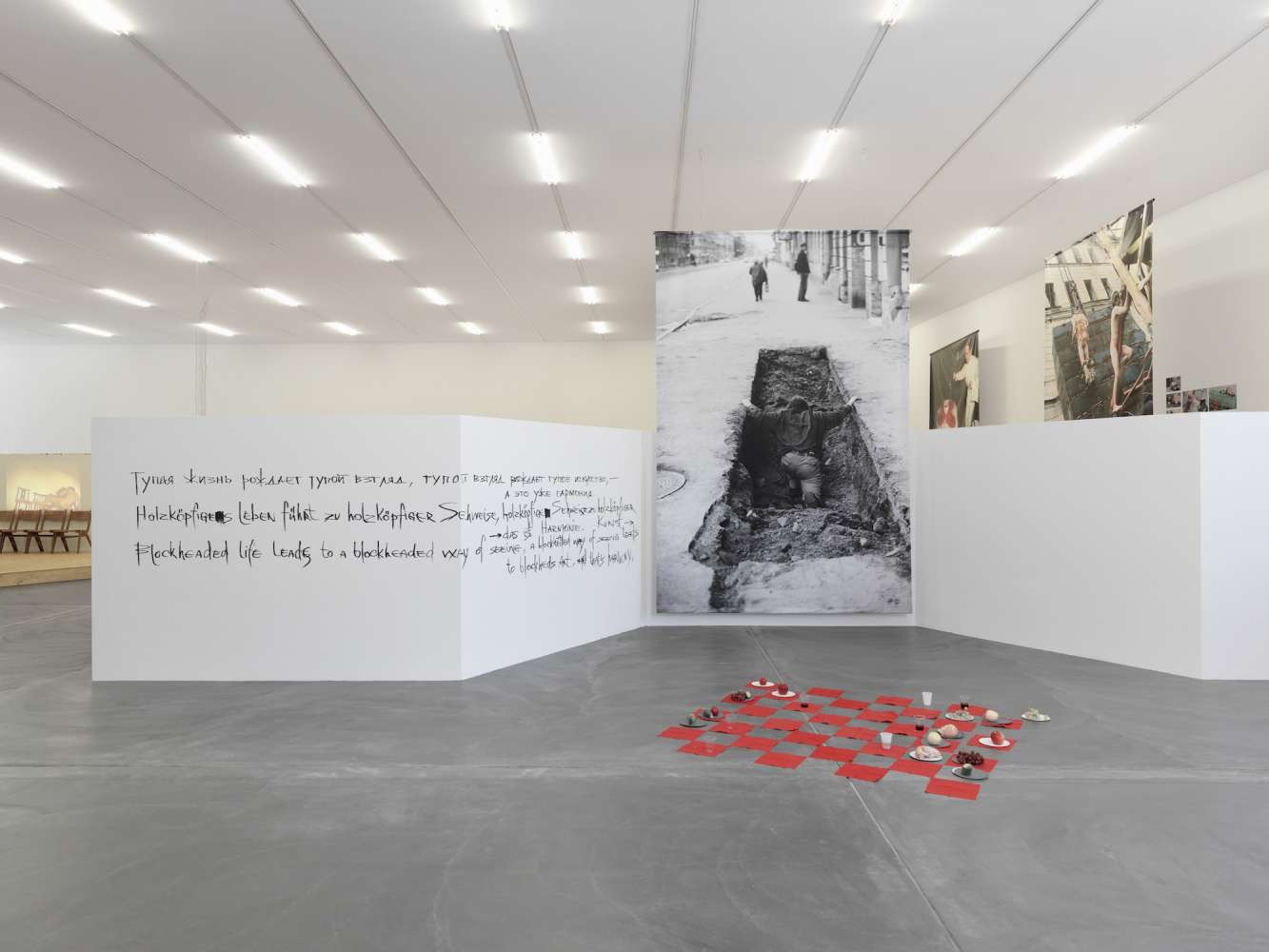

The Brotherhood of New Blockheads, installation view at Kunsthalle Zürich 2019, photo: Annika Wetter

The Brotherhood of New Blockheads, installation view at Kunsthalle Zürich 2019, photo: Annika Wetter

The Brotherhood of New Blockheads, installation view at Kunsthalle Zürich 2019, photo: Annika Wetter

The Brotherhood of New Blockheads, installation view at Kunsthalle Zürich 2019, photo: Annika Wetter

The Brotherhood of New Blockheads, installation view at Kunsthalle Zürich 2019, photo: Annika Wetter

The Brotherhood of New Blockheads, installation view at Kunsthalle Zürich 2019, photo: Annika Wetter

The Brotherhood of New Blockheads, installation view at Kunsthalle Zürich 2019, photo: Annika Wetter

The Brotherhood of New Blockheads, installation view at Kunsthalle Zürich 2019, photo: Annika Wetter

The Brotherhood of New Blockheads, installation view at Kunsthalle Zürich 2019, photo: Annika Wetter

Blessed Easter Sunday

Action, video performance

Shapkinskiye Lakes, Leningrad Region

11 April 1999

Artists: Vladimir Kozin, Igor Panin, Vadim Flyagin

Photo, video: Klavdia Alexeeva

Action, video performance

Shapkinskiye Lakes, Leningrad Region

11 April 1999

Artists: Vladimir Kozin, Igor Panin, Vadim Flyagin

Photo, video: Klavdia Alexeeva

THE BROTHERHOOD OF NEW BLOCKHEADS (1996–2002)

16 February – 26 May 2019

The New Blockheads - A Society of the Future

This ‘archival’ exhibition of The Brotherhood of New Blockheads (1996-2002) is special, being the first time the group has been presented officially on the international stage. In what way is the legacy of the New Blockheads of interest today? It is in part quite logical, for it was born in a time when a deficit in the present and a crisis of utopian ideals made looking to the past the only source of hope. Utterly in keeping with their own time, standing apart from any fixed styles or trends, The Brotherhood of New Blockheads was everything we could want of art: daring, despairing, naive, radical. Their legacy is relevant today for it provides a model for frank and uncompromising artistic behaviour, for maximum sincerity, something which is so keenly lacking in the world today.

In structure the group anticipated art’s current desire for interdisciplinarity. Its authors or members (Vadim Flyagin, Igor Panin, Sergey Spirikhin, Inga Nagel, Vladimir Kozin, Maksim Raiskin, Oleg Khvostov, and Alexander Lyashko) all came from different spheres, from the worlds of sculpture, philosophy, design, and literature. They were united not by a common style, as is usually the way with groups, but above all by their way of life, their way of thinking, by their desire to abjure prescribed roles, to return to the tabula rasa. Many of their actions or performances involved not only the members of the Brotherhood but some of the regulars at the group’s ‘parent’ gallery, Borey: idlers, drunks, artists, poets, and thinkers. A common aesthetic emerged from their search for a “new blockheaded view,” from reflections on life’s energetic pulse. This blockheaded view, suffused with almost excessive humanity—in contrast to just about everything else around them—was encapsulated in the last line of Vadim Flyagin’s manifesto, “Long live all Creatures!” Flyagin was to be the model for the Brotherhood’s lyrical hero. The predominantly literary approach of many performances was predetermined by the involvement of poet, philosopher, and hoaxer Sergey Spirikhin. With a taste for ritual parody, Vladimir Kozin created the meaningful basis for the performances, which he turned into something akin to a spiritual séance. Without any apparent effort the New Blockheads found themselves with their own journal, Maksimka, edited by Maksim Raiskin, with their own photographer, Alexander Lyashko, their own camp follower, Oleg Khvostov, and their own muse, Inga Nagel.

The time was the late 1990s and early 2000s, a very different time, when Russia was taking on new form and a period of as yet undefined hopes seemed to have arrived. A land of absolute prohibition had suddenly been transformed into a territory of barely defined borders, where everything was permitted. Finding themselves amidst the ruins of the Soviet empire, liberated but superfluous, artists were forced to assume a new identity. Russian society’s acute nervousness in the 1990s, people’s insecurity, the reassessment of key concepts and principles such as freedom, truth, religion, and morals—all had its effect on artistic output. Capitalism’s chaotic establishment in the new Russia was starkly reminiscent of the events surrounding the October Revolution in 1917, only the other way around. Revolutionary slogans—‘Factories to the workers, land to the peasants!,’ ‘Against the bourgeoisie and the capitalists!’—were turned upside-down in the 1990s in accordance with the state’s new ideology of total privatisation. The slogans proposed by the Blockheads were always absurd or parodically pacifist, making meaningless the very concept of demands, apparently underlining the revolutionary tradition on one hand while on the other profaning the very essence of collective consciousness. A huge banner stretched across the entrance to the Manege Central Exhibition Hall in St Petersburg, ‘Go to hell, art lovers,’ with its little flower drawn at the bottom, tells of the artist’s perpetual battle with the viewer, of the a priori comic Narcissism of the classical concept of the artist, of the Nietzschean loneliness of the unrecognised genius seated proudly on a promontory.

The interpretation of any situation—from a leak in the bathroom to the repairing of roads, from a demonstration to shopping for food—was immediately subject to a poetic form of critical assessment, and the readiness to create an improvised performance (or what the Blockheads called actions) without prior preparation, suddenly, throwing themselves into it wholeheartedly, became what we might call the group’s strategy.

Ordinary citizens, viewing them with a knowledge of the Russian tradition, saw them as holy fools and left them alone, while the police simply checked them out and moved on: some mysterious force seemed to protect the New Blockheads, enabling them, absolutely unhindered, to set up a desk on Palace Square in central St Petersburg, or to put out the Eternal Flame on the Field of Mars with an overcoat. Such petty hooliganism was not in the least malicious. Rather it seemed innocent, almost childlike.

Thus emerged the image of a hero who looks upon the world with a strange, utterly uncomprehending gaze. One of their first performances was even called Teach Yourself to See. Eyes bound, mouths stuffed with spoons containing flaming fluid. The performance emerged as a paraphrase of Heidegger’s What is called Thinking?, as a free visualisation of philosophical texts. The group burned with desire to be rid of all that had gone before, everything that had seemed to dominate—of the Soviet and the postmodern, even of the nonconformist. The underlying concept of their performance was, in essence, that the impossible is possible, and the burning liquid in the spoons was a symbol of the destruction of all barriers to comprehension.

Tradition. For the New Blockheads the idea of life as performance was based not merely on rapid recognition and assimilation of the Western artistic experience—something which swept through Russia in the post-perestroika period— but on deeprooted local traditions, from the heroes of folktales to the classics of the Russian avant-garde. For the Blockheads, fabulous subjects and the performances The Sledge moves by Itself and Roly-Poly overlap with the tradition of performative behaviour as practised by Russian Futurists such as Vladimir Mayakovsky, or with the absurdist poetry of Daniil Kharms. Victory over the Sun, the famous Futurist spectacle performed in 1913 with designs by Kazimir Malevich, verse by Velimir Khlebnikov, and music by Mikhail Matiushin, could well have been one of the Brotherhood’s own actions. Think of the New Blockheads’ multi-part Guppy, Stonemasons, and Gardener which, like Victory over the Sun, had its scenography that multiplied the absurdity of the 1990s by the absurdity of the participants’ actions, set in a jazz restaurant. Such ‘absurdity times 3,’ like the idea of unshackling the arts form a link between the classic Russian avant-garde and The Brotherhood of New Block- heads.In part we might even see the urban space itself as part of tradition. Actions such as The Movement of the Tea Table towards the Sunset or Under the Bridge, which unfolded in historic sites, on the one hand made the city into a traditional backdrop and on the other made it a full participant in the performance.

History. Immediately after their first performance, this synthetic alter ego, apparently created by their united forces, won the support of the writers, artists, and philosophers who hung around Borey Gallery. Thus the lyrical hero emerged, a collective body representing the artistic bohemians of the 1990s. In the work of the New Blockheads the bohemian world—of which they were very much part—moved away from traditional decadence to declarative innocence. Vladimir Flyagin’s text, Single man would like to meet, is a hymn to restlessness and loneliness.

The Blockheads’ performative practices— and there were more than eighty extended performances and an endless number of smaller ones—encompassed every aspect of the surrounding world. Active transformation of post-perestroika Russian society and the world was reflected in the New Blockheads’ activities as in a mirror. Current issues such as politics and religion took on a parodic tragic significance, as if children were playing at being grown-ups.

Their reaction to the war in Chechnya was Laundry Day, to war in Yugoslavia—Slavic Bazaar. Always emotional, always energetic. The washing of the Russian flag, a naive attempt to wash away shame, or the pools of bloody borsch that symbolised the bombing of Serbia, were in keeping with the idea of the ‘blockheaded’ view, a desire to do something, to take a position.

In the 1990s the Russian Orthodox Church laid claim to being the symbol of spiritual renaissance and inhabitants of the former USSR rapidly transformed themselves from Communists into Christians. The New Blockheads, as always giving things a sharp edge, taking reality to absurd extremes, revealing—both literally and metaphorically—the inner aesthetics of events, celebrated Easter or let fly a red arrow with the word ‘Exit’ up into the dome of a cathedral.

Russia’s new emerging ideology was immediately subjected to the artists’ critical assessment, but most of the New Blockheads’ actions were jolly affairs: the merriment of survivors of the collapse of a house, looking forward with hope to the building of a new one. That was probably why the names of so many of the New Blockheads’ performances start with the word ‘Russian’: they even came up with the overall title ‘Central Russian Elevated Stupidity Project.’ The word ‘Russian’ is quite deliberate, in this instance acting as a sign, a subconscious desire to appropriate new experience, to do it themselves, to re-invent.

Purely practical aspects of the period—the deficit of foodstuffs and consumer goods—dictated a certain asceticism of style. The objective world of performances by The Brotherhood of New Blockheads was very simple: an electric hob, a saucepan, a table, a chair, a candle, insoles, a bucket, and spade. Sometimes it was the very lack of objects that dictated the content. The simplest foodstuff became a symbol, taking on meanings that are not always entirely comprehensible today. Everyone was familiar with hunger and a limited range of food, even with rationing, back in the USSR. It took a while to get used to capitalist abundance and so in the mind of post-Soviet man food retained something of the sacred, cult object.

Preparations for the display of the New Blockheads’s archive took several years. Small retrospective shows often served as an introduction to larger exhibitions, showing them as one source of a new stage in contemporary Russian art. For so they were in truth: the New Blockheads took shape in the post-Soviet space and from the very first they lacked the underlying agenda of protest against the powers-that-be that was characteristic of nonconformist art in the USSR (Ilya Kabakov, Erik Bulatov, and others): such art that had reached its natural conclusion along with the ending of ‘official’ art. What replaced it was essentially a new kind of critical attitude, often expressed as a kind of empathy, in which the artist does not set himself up against society but rapidly becomes part of it, part of any of its manifestations. Preserving collegial ties, armed with the naivety of the untaught but talented provincial who hungrily absorbs everything he comes across, the New Blockheads advanced into the unknown, into the very newest and latest history of art. That time of utter freedom bordering on anarchy and the extremely favourable creative climate allowed them to exist unfettered, making them—to many—a model of the unsullied artistic consciousness.

Performance is one of the most difficult subjects to present in an exhibition. No documentation, however full and comprehensive, can ever recreate the unique sense of physical presence. The inevitable loss of the work’s aura of which Walter Benjamin wrote has particularly relevance to performance: hence this retrospective is but an attempt to create a model of something elusive. The inherent and insuperable conflict between the retrospective exhibition, which unintentionally gives everything a commemorative or memorial tone, and the incredibly vivid, living phenomenon that was The Brotherhood of New Blockheads presents the curator with the task of creating corridors of meaning to help spectators find their way, of seeking points of reference in the current situation that resonate with the period in question. Over the fifteen years that have passed since the group broke up, much of what they did has been shown to have passed the test of time and indeed often seems almost prophetic. The light-hearted mood of the majority of their performances reflected not only the age in which they took place but the very nature and meaning of artistic and human existence.

Peter Belyi, Curator of the exhibition

Peter Belyi (b. 1965) is an artist and curator, member of Saint Petersburg Union of Artists since 1994, active member of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers since 1999. He received a Master’s degree in Printmaking from Camberwell College of Art in London in 2000. He is currently a lecturer at the Department of Liberal Arts and Sciences of Saint Petersburg State University and has founded Lyuda Gallery in St. Petersburg. He is a recipient of Innovation Prize for The Best Curating Project (2014) and Sergey Kuryokhin Prize for The Best Work of Visual Art (2009). He took part in the Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art (2008, 2013), and several projects of parallel and special programs of the 55th and 56th Venice Biennales, as well as in the parallel program of Manifesta 10. He lives and works in Saint Petersburg.

16 February – 26 May 2019

The New Blockheads - A Society of the Future

This ‘archival’ exhibition of The Brotherhood of New Blockheads (1996-2002) is special, being the first time the group has been presented officially on the international stage. In what way is the legacy of the New Blockheads of interest today? It is in part quite logical, for it was born in a time when a deficit in the present and a crisis of utopian ideals made looking to the past the only source of hope. Utterly in keeping with their own time, standing apart from any fixed styles or trends, The Brotherhood of New Blockheads was everything we could want of art: daring, despairing, naive, radical. Their legacy is relevant today for it provides a model for frank and uncompromising artistic behaviour, for maximum sincerity, something which is so keenly lacking in the world today.

In structure the group anticipated art’s current desire for interdisciplinarity. Its authors or members (Vadim Flyagin, Igor Panin, Sergey Spirikhin, Inga Nagel, Vladimir Kozin, Maksim Raiskin, Oleg Khvostov, and Alexander Lyashko) all came from different spheres, from the worlds of sculpture, philosophy, design, and literature. They were united not by a common style, as is usually the way with groups, but above all by their way of life, their way of thinking, by their desire to abjure prescribed roles, to return to the tabula rasa. Many of their actions or performances involved not only the members of the Brotherhood but some of the regulars at the group’s ‘parent’ gallery, Borey: idlers, drunks, artists, poets, and thinkers. A common aesthetic emerged from their search for a “new blockheaded view,” from reflections on life’s energetic pulse. This blockheaded view, suffused with almost excessive humanity—in contrast to just about everything else around them—was encapsulated in the last line of Vadim Flyagin’s manifesto, “Long live all Creatures!” Flyagin was to be the model for the Brotherhood’s lyrical hero. The predominantly literary approach of many performances was predetermined by the involvement of poet, philosopher, and hoaxer Sergey Spirikhin. With a taste for ritual parody, Vladimir Kozin created the meaningful basis for the performances, which he turned into something akin to a spiritual séance. Without any apparent effort the New Blockheads found themselves with their own journal, Maksimka, edited by Maksim Raiskin, with their own photographer, Alexander Lyashko, their own camp follower, Oleg Khvostov, and their own muse, Inga Nagel.

The time was the late 1990s and early 2000s, a very different time, when Russia was taking on new form and a period of as yet undefined hopes seemed to have arrived. A land of absolute prohibition had suddenly been transformed into a territory of barely defined borders, where everything was permitted. Finding themselves amidst the ruins of the Soviet empire, liberated but superfluous, artists were forced to assume a new identity. Russian society’s acute nervousness in the 1990s, people’s insecurity, the reassessment of key concepts and principles such as freedom, truth, religion, and morals—all had its effect on artistic output. Capitalism’s chaotic establishment in the new Russia was starkly reminiscent of the events surrounding the October Revolution in 1917, only the other way around. Revolutionary slogans—‘Factories to the workers, land to the peasants!,’ ‘Against the bourgeoisie and the capitalists!’—were turned upside-down in the 1990s in accordance with the state’s new ideology of total privatisation. The slogans proposed by the Blockheads were always absurd or parodically pacifist, making meaningless the very concept of demands, apparently underlining the revolutionary tradition on one hand while on the other profaning the very essence of collective consciousness. A huge banner stretched across the entrance to the Manege Central Exhibition Hall in St Petersburg, ‘Go to hell, art lovers,’ with its little flower drawn at the bottom, tells of the artist’s perpetual battle with the viewer, of the a priori comic Narcissism of the classical concept of the artist, of the Nietzschean loneliness of the unrecognised genius seated proudly on a promontory.

The interpretation of any situation—from a leak in the bathroom to the repairing of roads, from a demonstration to shopping for food—was immediately subject to a poetic form of critical assessment, and the readiness to create an improvised performance (or what the Blockheads called actions) without prior preparation, suddenly, throwing themselves into it wholeheartedly, became what we might call the group’s strategy.

Ordinary citizens, viewing them with a knowledge of the Russian tradition, saw them as holy fools and left them alone, while the police simply checked them out and moved on: some mysterious force seemed to protect the New Blockheads, enabling them, absolutely unhindered, to set up a desk on Palace Square in central St Petersburg, or to put out the Eternal Flame on the Field of Mars with an overcoat. Such petty hooliganism was not in the least malicious. Rather it seemed innocent, almost childlike.

Thus emerged the image of a hero who looks upon the world with a strange, utterly uncomprehending gaze. One of their first performances was even called Teach Yourself to See. Eyes bound, mouths stuffed with spoons containing flaming fluid. The performance emerged as a paraphrase of Heidegger’s What is called Thinking?, as a free visualisation of philosophical texts. The group burned with desire to be rid of all that had gone before, everything that had seemed to dominate—of the Soviet and the postmodern, even of the nonconformist. The underlying concept of their performance was, in essence, that the impossible is possible, and the burning liquid in the spoons was a symbol of the destruction of all barriers to comprehension.

Tradition. For the New Blockheads the idea of life as performance was based not merely on rapid recognition and assimilation of the Western artistic experience—something which swept through Russia in the post-perestroika period— but on deeprooted local traditions, from the heroes of folktales to the classics of the Russian avant-garde. For the Blockheads, fabulous subjects and the performances The Sledge moves by Itself and Roly-Poly overlap with the tradition of performative behaviour as practised by Russian Futurists such as Vladimir Mayakovsky, or with the absurdist poetry of Daniil Kharms. Victory over the Sun, the famous Futurist spectacle performed in 1913 with designs by Kazimir Malevich, verse by Velimir Khlebnikov, and music by Mikhail Matiushin, could well have been one of the Brotherhood’s own actions. Think of the New Blockheads’ multi-part Guppy, Stonemasons, and Gardener which, like Victory over the Sun, had its scenography that multiplied the absurdity of the 1990s by the absurdity of the participants’ actions, set in a jazz restaurant. Such ‘absurdity times 3,’ like the idea of unshackling the arts form a link between the classic Russian avant-garde and The Brotherhood of New Block- heads.In part we might even see the urban space itself as part of tradition. Actions such as The Movement of the Tea Table towards the Sunset or Under the Bridge, which unfolded in historic sites, on the one hand made the city into a traditional backdrop and on the other made it a full participant in the performance.

History. Immediately after their first performance, this synthetic alter ego, apparently created by their united forces, won the support of the writers, artists, and philosophers who hung around Borey Gallery. Thus the lyrical hero emerged, a collective body representing the artistic bohemians of the 1990s. In the work of the New Blockheads the bohemian world—of which they were very much part—moved away from traditional decadence to declarative innocence. Vladimir Flyagin’s text, Single man would like to meet, is a hymn to restlessness and loneliness.

The Blockheads’ performative practices— and there were more than eighty extended performances and an endless number of smaller ones—encompassed every aspect of the surrounding world. Active transformation of post-perestroika Russian society and the world was reflected in the New Blockheads’ activities as in a mirror. Current issues such as politics and religion took on a parodic tragic significance, as if children were playing at being grown-ups.

Their reaction to the war in Chechnya was Laundry Day, to war in Yugoslavia—Slavic Bazaar. Always emotional, always energetic. The washing of the Russian flag, a naive attempt to wash away shame, or the pools of bloody borsch that symbolised the bombing of Serbia, were in keeping with the idea of the ‘blockheaded’ view, a desire to do something, to take a position.

In the 1990s the Russian Orthodox Church laid claim to being the symbol of spiritual renaissance and inhabitants of the former USSR rapidly transformed themselves from Communists into Christians. The New Blockheads, as always giving things a sharp edge, taking reality to absurd extremes, revealing—both literally and metaphorically—the inner aesthetics of events, celebrated Easter or let fly a red arrow with the word ‘Exit’ up into the dome of a cathedral.

Russia’s new emerging ideology was immediately subjected to the artists’ critical assessment, but most of the New Blockheads’ actions were jolly affairs: the merriment of survivors of the collapse of a house, looking forward with hope to the building of a new one. That was probably why the names of so many of the New Blockheads’ performances start with the word ‘Russian’: they even came up with the overall title ‘Central Russian Elevated Stupidity Project.’ The word ‘Russian’ is quite deliberate, in this instance acting as a sign, a subconscious desire to appropriate new experience, to do it themselves, to re-invent.

Purely practical aspects of the period—the deficit of foodstuffs and consumer goods—dictated a certain asceticism of style. The objective world of performances by The Brotherhood of New Blockheads was very simple: an electric hob, a saucepan, a table, a chair, a candle, insoles, a bucket, and spade. Sometimes it was the very lack of objects that dictated the content. The simplest foodstuff became a symbol, taking on meanings that are not always entirely comprehensible today. Everyone was familiar with hunger and a limited range of food, even with rationing, back in the USSR. It took a while to get used to capitalist abundance and so in the mind of post-Soviet man food retained something of the sacred, cult object.

Preparations for the display of the New Blockheads’s archive took several years. Small retrospective shows often served as an introduction to larger exhibitions, showing them as one source of a new stage in contemporary Russian art. For so they were in truth: the New Blockheads took shape in the post-Soviet space and from the very first they lacked the underlying agenda of protest against the powers-that-be that was characteristic of nonconformist art in the USSR (Ilya Kabakov, Erik Bulatov, and others): such art that had reached its natural conclusion along with the ending of ‘official’ art. What replaced it was essentially a new kind of critical attitude, often expressed as a kind of empathy, in which the artist does not set himself up against society but rapidly becomes part of it, part of any of its manifestations. Preserving collegial ties, armed with the naivety of the untaught but talented provincial who hungrily absorbs everything he comes across, the New Blockheads advanced into the unknown, into the very newest and latest history of art. That time of utter freedom bordering on anarchy and the extremely favourable creative climate allowed them to exist unfettered, making them—to many—a model of the unsullied artistic consciousness.

Performance is one of the most difficult subjects to present in an exhibition. No documentation, however full and comprehensive, can ever recreate the unique sense of physical presence. The inevitable loss of the work’s aura of which Walter Benjamin wrote has particularly relevance to performance: hence this retrospective is but an attempt to create a model of something elusive. The inherent and insuperable conflict between the retrospective exhibition, which unintentionally gives everything a commemorative or memorial tone, and the incredibly vivid, living phenomenon that was The Brotherhood of New Blockheads presents the curator with the task of creating corridors of meaning to help spectators find their way, of seeking points of reference in the current situation that resonate with the period in question. Over the fifteen years that have passed since the group broke up, much of what they did has been shown to have passed the test of time and indeed often seems almost prophetic. The light-hearted mood of the majority of their performances reflected not only the age in which they took place but the very nature and meaning of artistic and human existence.

Peter Belyi, Curator of the exhibition

Peter Belyi (b. 1965) is an artist and curator, member of Saint Petersburg Union of Artists since 1994, active member of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers since 1999. He received a Master’s degree in Printmaking from Camberwell College of Art in London in 2000. He is currently a lecturer at the Department of Liberal Arts and Sciences of Saint Petersburg State University and has founded Lyuda Gallery in St. Petersburg. He is a recipient of Innovation Prize for The Best Curating Project (2014) and Sergey Kuryokhin Prize for The Best Work of Visual Art (2009). He took part in the Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art (2008, 2013), and several projects of parallel and special programs of the 55th and 56th Venice Biennales, as well as in the parallel program of Manifesta 10. He lives and works in Saint Petersburg.