Dan Flavin

Dedications in Lights

02 Mar - 18 Aug 2024

Curators: Josef Helfenstein, Olga Osadtschy, Elena Degen

Under the title Dan Flavin. Dedications in Lights, the Kunstmuseum Basel dedicates an extensive special exhibition at its Neubau venue to a pioneer of Minimal Art: the American artist Dan Flavin (1933–1996) rose to fame in the early 1960s with his work with industrially manufactured fluorescent tubes. Showcasing fifty-eight works, some of which have never been on view in Switzerland, the exhibition presents a thematically as well as chronologically organized survey of Flavin’s singular oeuvre, with a focus on works he dedicated to individuals or events. It is the artist’s first major show in Switzerland in twelve years.

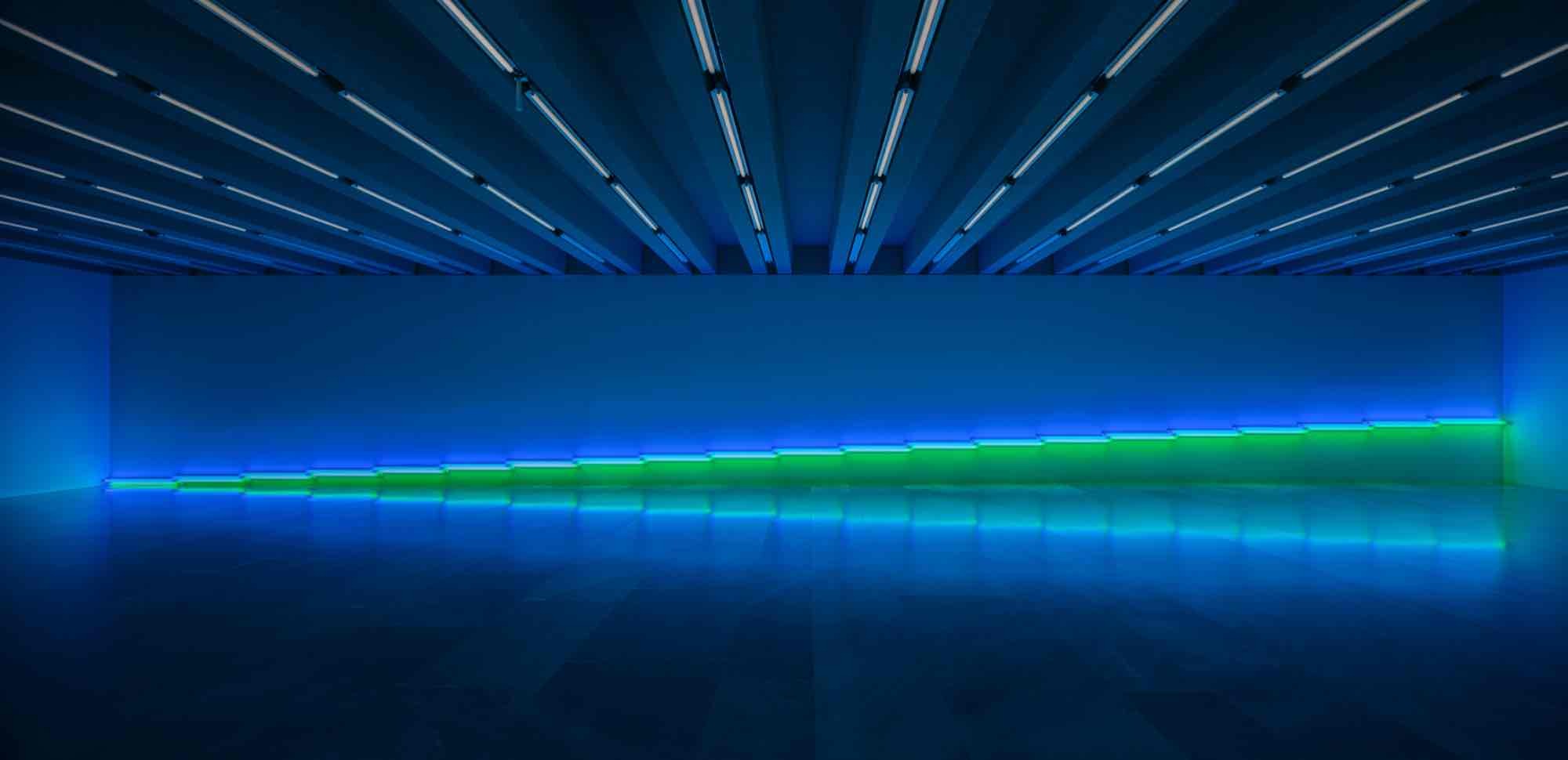

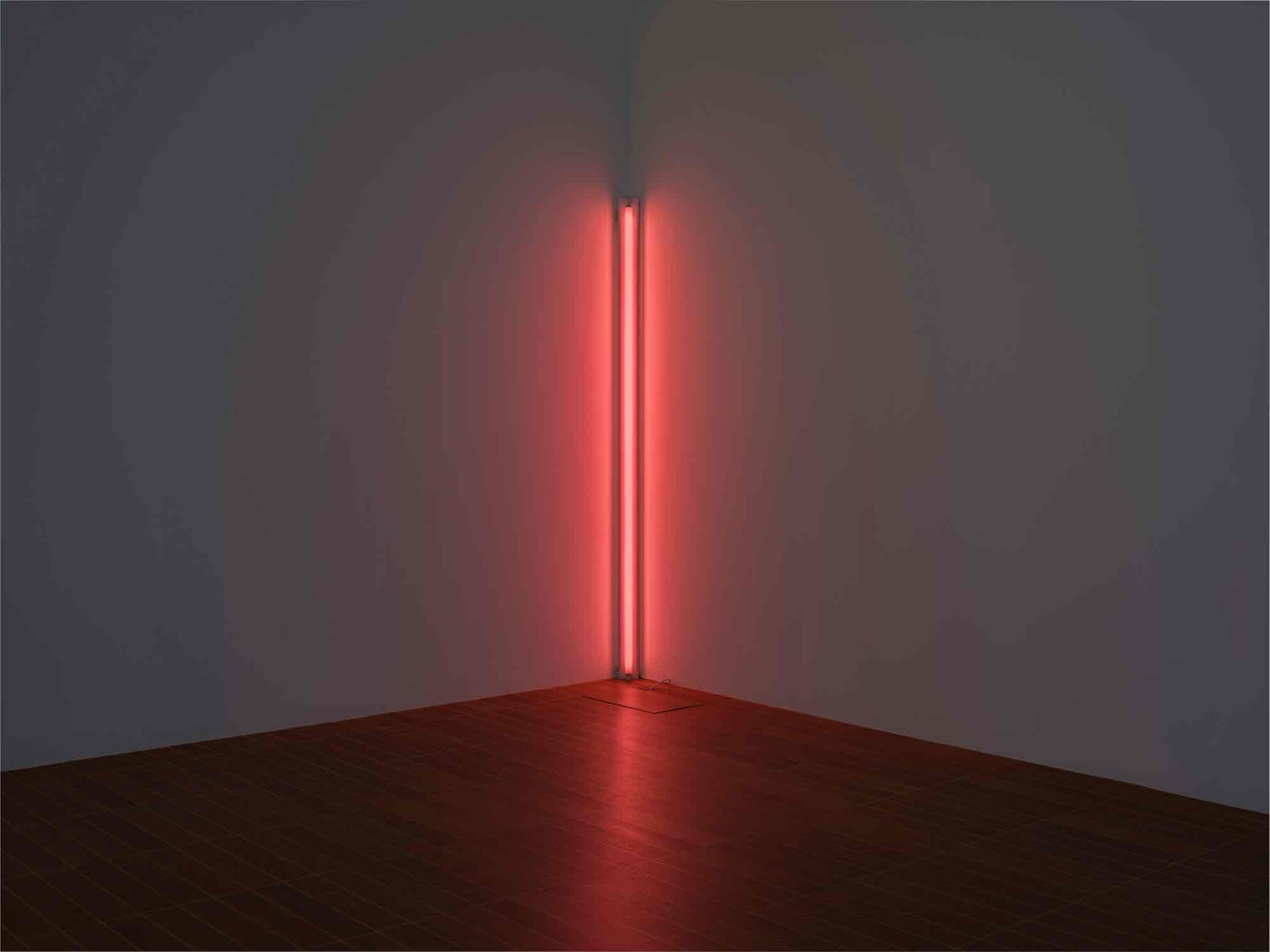

Dan Flavin made history by creating a new art form. His works made of light extricated color from the context of painting and transposed it into three-dimensional space. Using commercially available light fixtures, he defied conventional ideas about authorship and processes of art production: His decision to make art out of a mundane utilitarian object, radical even by today’s standards, caused a stir among his contemporaries. The earliest exhibitions of Flavin’s fluorescent lamps in New York left artists and critics thrilled by his purism, the fascination of his “gaseous images” (a term the artist himself liked to use), and the physical immediacy of their glowing presence.

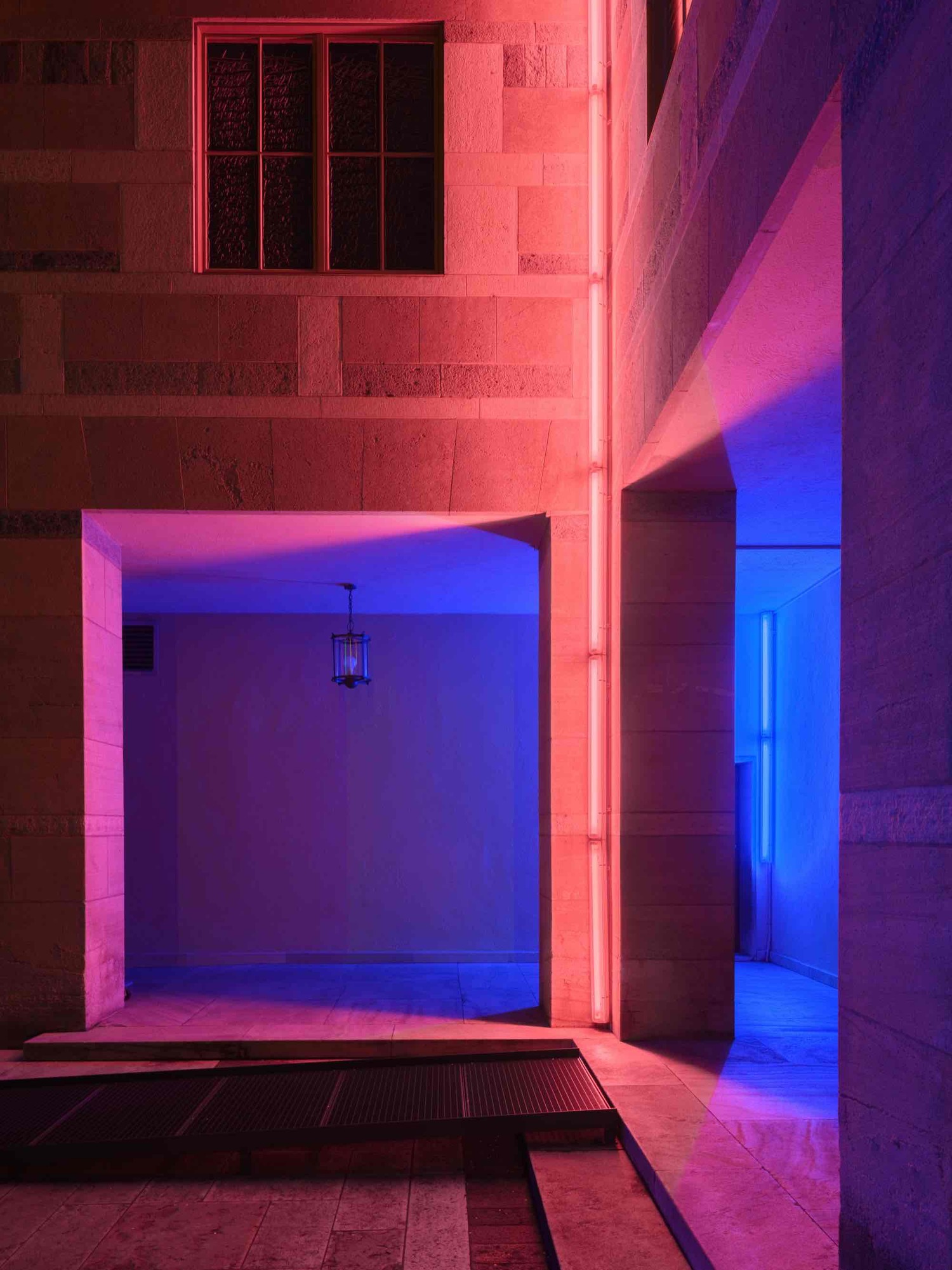

Flavin’s fluorescent tubes bring to mind factory halls, fast-food restaurants, and parking lots. The artist leveraged this effect and the limited palette of colors—blue, green, red, pink, yellow, ultraviolet, and four different shades of white—predetermined by the technology. In the course of his career, single tubes and simple geometric arrangements evolved into complex architectonic works and elaborate multipart series. Flavin insistently rejected the designation “sculpture” or “painting” for his works, which he preferred to characterize as “situations.” In his writings and other statements, he moreover emphasized the factual quality of his art. In the catalogue accompanying his first major work for an institution, installed at the Van Abbemuseum in 1966, he wrote: “Electric light is just another instrument. I have no desire to contrive fantasies mediumistically or sociologically over it or beyond it. (…) I do whatever I can whenever I can with whatever I have wherever I am.”

Flavin’s uncompromising self-limitation to working with a single industrially manufactured object and the serial quality of his creations arguably aligns his oeuvre with Minimal Art. Besides Flavin, Carl Andre, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Morris are widely regarded as the movement’s leading protagonists—though each of them more or less firmly repudiated the label.

The dedications

Flavin championed an art that does not aim for any profound psychological and spiritual impact and is instead meant to be perceived in passing. The artist himself negated the symbolic tenor of his work and disregarded its sometimes sublime effect. Yet as numerous art critics have pointed out, Flavin’s work can nonetheless be connected to Christian and metaphysical motifs, suggesting allusions to spaces of prayer and meditation illuminated by votive candles. He rebuffed such views with the ironic dictum “It is what it is and it ain’t nothin’ else.”

What is striking, though, is that Flavin habitually dedicated his works throughout his career, associating them, often in sentimental and solemn fashion, with individuals or events. Many of the fluorescent light installations he produced from 1963 on are dedicated to artist friends like Jasper Johns, Sol LeWitt, and Donald Judd. Modernists like Henri Matisse, Vladimir Tatlin, and Otto Freundlich likewise make appearances in Flavin’s titles. These dedications stand in deliberate contrast with the anonymity of the material. By integrating them into his titles, Flavin anchored the non-narrative and impersonal works in a specific aesthetic, political, and social context.

The constitutive role of the titles is also salient when Flavin makes reference to political events. Some works commemorate wartime atrocities and must be read in connection with Flavin’s outspoken opposition to the Vietnam War: see, for instance, monument 4 for those who have been killed in ambush (to P.K. who reminded me about death), which he showed in the exhibition Primary Structures. Younger American and British Sculptors at the Jewish Museum, New York, in 1966, one of the first institutional presentations of the rising minimalist movement’s output.

No less remarkable are the pieces that Flavin dedicated to people he worked with. A prominent example in the exhibition is untitled (to you, Heiner, with admiration and affection), dedicated to the legendary German art dealer Heiner Friedrich. After immigrating to the U.S., Friedrich, in 1974, founded the influential Dia Art Foundation, which supports the permanent and publicly accessible installation of works by a group of artists of the 1960s and 1970s. The work from the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, is a so-called “barrier,” a type that Flavin developed in order to close off part of the exhibition space to visitors.

Taking many different forms, the dedications introduce an emotional dimension and highlight the web of artistic and literary references and personal relationships that informed Flavin’s work. One central objective of the exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Basel is to throw this dimension of his art into relief.

In addition to Flavin’s installations, some of which take up entire rooms, the presentation includes drawings: portraits and depictions of nature that have received comparatively little public attention as well as sketches for works and diagrams. The small notebooks he kept were a vital tool for Flavin and constitute a kind of archive of his oeuvre, which spans over three decades. Last but not least, the exhibition brings into focus the social and historical context in which Flavin’s seminal earliest works with light came into being.

Under the title Dan Flavin. Dedications in Lights, the Kunstmuseum Basel dedicates an extensive special exhibition at its Neubau venue to a pioneer of Minimal Art: the American artist Dan Flavin (1933–1996) rose to fame in the early 1960s with his work with industrially manufactured fluorescent tubes. Showcasing fifty-eight works, some of which have never been on view in Switzerland, the exhibition presents a thematically as well as chronologically organized survey of Flavin’s singular oeuvre, with a focus on works he dedicated to individuals or events. It is the artist’s first major show in Switzerland in twelve years.

Dan Flavin made history by creating a new art form. His works made of light extricated color from the context of painting and transposed it into three-dimensional space. Using commercially available light fixtures, he defied conventional ideas about authorship and processes of art production: His decision to make art out of a mundane utilitarian object, radical even by today’s standards, caused a stir among his contemporaries. The earliest exhibitions of Flavin’s fluorescent lamps in New York left artists and critics thrilled by his purism, the fascination of his “gaseous images” (a term the artist himself liked to use), and the physical immediacy of their glowing presence.

Flavin’s fluorescent tubes bring to mind factory halls, fast-food restaurants, and parking lots. The artist leveraged this effect and the limited palette of colors—blue, green, red, pink, yellow, ultraviolet, and four different shades of white—predetermined by the technology. In the course of his career, single tubes and simple geometric arrangements evolved into complex architectonic works and elaborate multipart series. Flavin insistently rejected the designation “sculpture” or “painting” for his works, which he preferred to characterize as “situations.” In his writings and other statements, he moreover emphasized the factual quality of his art. In the catalogue accompanying his first major work for an institution, installed at the Van Abbemuseum in 1966, he wrote: “Electric light is just another instrument. I have no desire to contrive fantasies mediumistically or sociologically over it or beyond it. (…) I do whatever I can whenever I can with whatever I have wherever I am.”

Flavin’s uncompromising self-limitation to working with a single industrially manufactured object and the serial quality of his creations arguably aligns his oeuvre with Minimal Art. Besides Flavin, Carl Andre, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Morris are widely regarded as the movement’s leading protagonists—though each of them more or less firmly repudiated the label.

The dedications

Flavin championed an art that does not aim for any profound psychological and spiritual impact and is instead meant to be perceived in passing. The artist himself negated the symbolic tenor of his work and disregarded its sometimes sublime effect. Yet as numerous art critics have pointed out, Flavin’s work can nonetheless be connected to Christian and metaphysical motifs, suggesting allusions to spaces of prayer and meditation illuminated by votive candles. He rebuffed such views with the ironic dictum “It is what it is and it ain’t nothin’ else.”

What is striking, though, is that Flavin habitually dedicated his works throughout his career, associating them, often in sentimental and solemn fashion, with individuals or events. Many of the fluorescent light installations he produced from 1963 on are dedicated to artist friends like Jasper Johns, Sol LeWitt, and Donald Judd. Modernists like Henri Matisse, Vladimir Tatlin, and Otto Freundlich likewise make appearances in Flavin’s titles. These dedications stand in deliberate contrast with the anonymity of the material. By integrating them into his titles, Flavin anchored the non-narrative and impersonal works in a specific aesthetic, political, and social context.

The constitutive role of the titles is also salient when Flavin makes reference to political events. Some works commemorate wartime atrocities and must be read in connection with Flavin’s outspoken opposition to the Vietnam War: see, for instance, monument 4 for those who have been killed in ambush (to P.K. who reminded me about death), which he showed in the exhibition Primary Structures. Younger American and British Sculptors at the Jewish Museum, New York, in 1966, one of the first institutional presentations of the rising minimalist movement’s output.

No less remarkable are the pieces that Flavin dedicated to people he worked with. A prominent example in the exhibition is untitled (to you, Heiner, with admiration and affection), dedicated to the legendary German art dealer Heiner Friedrich. After immigrating to the U.S., Friedrich, in 1974, founded the influential Dia Art Foundation, which supports the permanent and publicly accessible installation of works by a group of artists of the 1960s and 1970s. The work from the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, is a so-called “barrier,” a type that Flavin developed in order to close off part of the exhibition space to visitors.

Taking many different forms, the dedications introduce an emotional dimension and highlight the web of artistic and literary references and personal relationships that informed Flavin’s work. One central objective of the exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Basel is to throw this dimension of his art into relief.

In addition to Flavin’s installations, some of which take up entire rooms, the presentation includes drawings: portraits and depictions of nature that have received comparatively little public attention as well as sketches for works and diagrams. The small notebooks he kept were a vital tool for Flavin and constitute a kind of archive of his oeuvre, which spans over three decades. Last but not least, the exhibition brings into focus the social and historical context in which Flavin’s seminal earliest works with light came into being.