Karla Black

27 Jun - 02 Nov 2025

Karla Black, Kunstraum Dornbirn 2025, Photo Günter Richard Wett, © Karla Black, Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and Modern Art, London.

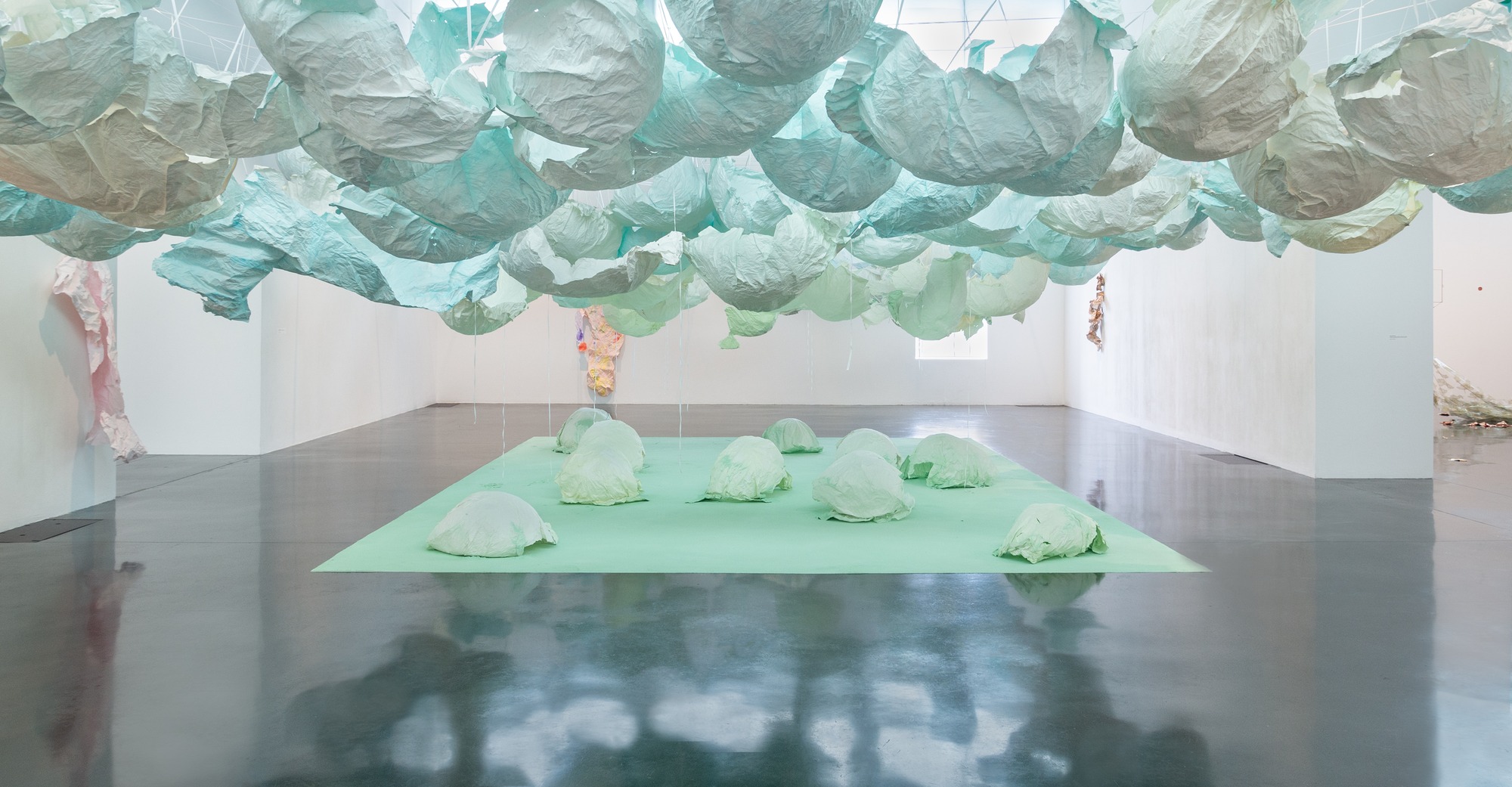

Karla Black, 'Safety As A Stance', 2025, installation view 'Karla Black', Kunstraum Dornbirn 2025, Photo Günter Richard Wett, © Karla Black, Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and Modern Art, London.

Karla Black, 'Looking Glass (picture grid)', 2025, installation view 'Karla Black', Kunstraum Dornbirn 2025, Photo Günter Richard Wett, © Karla Black, Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and Modern Art, London.

Karla Black, 'Safety As A Stance', 2025, installation view 'Karla Black', Kunstraum Dornbirn 2025, Photo Günter Richard Wett, © Karla Black, Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and Modern Art, London.

Karla Black, 'Safety As A Stance', 2025, installation view 'Karla Black', Kunstraum Dornbirn 2025, Photo Günter Richard Wett, © Karla Black, Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and Modern Art, London.

Dense, pastel-coloured and inviting, Karla Black’s new work at Kunstraum Dornbirn is a sight to behold. The Scottish artist has designed a landscape for the former assembly hall that invites visitors to wander, marvel and enjoy. Using everyday materials, some of which are unusual for art, she creates a space-filling combination of material, form and colour, a blissful experience appealing to all the senses.

From the 11-metre-high ceiling hang countless strips of lightly coloured toilet paper throughout the room. Between them are strings from which hang silhouettes of hemispheres moulded in paper or translucent coloured foils, tied together to form wondrous, graceful shapes. The dangling and floating spheres are visually offset by the standing and reclining forms: in the clearings between the toilet paper and the strings, sculptures are placed that poetically combine standing paper and holding plaster moulds. The toilet paper ends on the floor, on surfaces made of sieved gypsum and pigment powder. The strips run out in these areas, the last, recumbent leaves covered by powder. The edges of the differently coloured areas are framed by crinkled toilet paper. Bath bombs in the form of cake pieces or in a floral design as well as make-up beads are scattered over the coloured ground. These floor works, covering the entire surface, create paths on which we can enter the fantastic landscape entitled “Safety As A Stance”. They also give the room a harmonious pastel palette of colours ranging from pink to peach to beige and yellow. When daylight or sunlight strikes the materials, they glow in their pastel hues and colour the entire ambience. This considerably intensifies the holistic experience of material and colour.

Sometimes we catch a glimpse of ourselves in the room: Under the title “Looking Glass (picture grid)”, Black has panelled the rear long side of the hall with numerous mirrors in the alcoves of the huge lattice windows. Some of the panels are hand-painted, showing markings and colourful gestures on the reflective surface. The doubling of the mirrored images and consequent enlargement of the room has an expansive effect and dissolves the tangible space into fragments.

The Dornbirn exhibition vividly illustrates the great power that Black infuses into her artistic language, which is based on a formal aesthetic understanding of sculpture, that is, on the pure form and effect of the artwork. She says: “My work is essentially formal. Its main interest is aesthetic. […] What goes on in it is the processing and reprocessing of the relationship between colour, form, material and composition.” (Karla Black, Kunstforum International, vol. 227 (2014): 209-210.) The depiction is always abstract, never figurative. Physical representation of the human form is exclusively through the bodily presence of visitors or in her gesturally painted mirror works, whose impasto application of paint or occasional omissions manifest indistinct or fragmented reflections.

The work is abstract not only in terms of what is depicted, but also in terms of the materials chosen and how they are used. This is because no fixed and often no permanent form is given them. For example, if gypsum powder is used, it is not mixed with water to form a hardening mass as usual, but is applied in its original state. It is sieved, layered, dusted over foils and much else besides. The fact that the material could potentially have a fixed form in the next step of the process leaves it in a seemingly unfinished state. This example makes clear that the properties and purpose of materials are linked to directives for their use, directives that Black refuses to carry out. This gives her work a very appealing indeterminacy, a state between raw and finished.

The starting point of all Black’s work is her enjoyment of working with a particular material. The type of material is not important. The palette employs not only traditional art materials, such as acrylic paint, pigment or plaster, but also incorporates any materials from everyday life that serves the purpose, including plastic film, soap, make-up or toilet paper. By contrast, the medium to which Black assigns her work is clearly defined: it is sculpture. In her practice, she also experiments with other genres, and her works are impressive spatial experiences drawing freely and uninhibitedly on painting, installation, environment and performance. But despite her forays into other media, Black’s presentations are always sculpture exhibitions. Playfully but precisely put to the test, anchored in material aesthetics, the boundaries and possibilities of the concept of sculpture are constantly submitted to broader interrogation.

Black creates immersive situations in which the ephemeral fragility of materials such as powder or paper is paired with the strength and durability of the meticulously space-filling formats. In Dornbirn, she combines existing works with new creations and with sculptural strategies and elements that seem familiar from previous productions. This sense of recognition allows us to understand the development and function of the new combination within her elaborated formal-aesthetic approach. The method of production derives from the physical conditions, which include her own state of being as well as the architecture and its spatial specifications. Within this framework, Black primarily responds emotionally, drawing on a realm beyond language, such as unconscious intuition. In a careful process of sifting, layering, piling and heaping, knotting, hanging and smearing her materials, Black gives them form in situ in the exhibition space. The intuitive beginning is accompanied in the next steps by conscious intention, by consideration of those very physical conditions and their final form and effect.

The aesthetic effect – meaning on the one hand beauty, and on the other hand the nature of the materials, the composition of the elements, and the experience and sensory enjoyment of the works – is self-referential and uncompromising, purified of any external meaning, and the most important category. Yet in Dornbirn, we can see that creative references related to content can still play a role: Black’s floor installations create a freedom of movement that allows us to enter into them. The surfaces surrounded by toilet paper look like flowerbeds, and the association with garden designs, in which plantings become elaborate ornamental formations, is no accident. Since the beginning of the project, the partially mirrored windows of the assembly hall have been an integral part of the exhibition. Black herself formulates clear references to garden design and the famous Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. Not only the structure of the assembly hall’s windows resemble the mirrored niches of Versailles – Black’s entire form language and colour choice has also been recognisably influenced by Baroque and Rococo design elements. Their playful aesthetics, with flowing lines, billowing fabrics, asymmetry, pastel tones and nature-inspired motifs, found its way into her work. Abstracting these aspects and combing them with her own vocabulary of materials, Black creates the unique formal language that has made her internationally renowned.

Biography Karla Black was born in 1972 in Alexandria, UK, and lives and works in Glasgow, UK. She represented Scotland at the 57th Venice Biennale (2011) and her work was exhibited at Manifesta 10 at St Petersburg (2014). Her immersive, often site-specific installations have been shown at numerous solo exhibitions, for example at the Bechtler Foundation, Uster (2024), New Art Gallery Walsall (2023), Modern Art Gallery, London (2022), Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh (2021), Des Moines Art Centre (2020), Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt (2019), Le Festival d’Automne, Paris (2017), Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle (2017), Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh (2016), Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (2016), Gemeentemuseum, The Hague (2013), Dallas Museum of Art (2012) and Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow (2012).

From the 11-metre-high ceiling hang countless strips of lightly coloured toilet paper throughout the room. Between them are strings from which hang silhouettes of hemispheres moulded in paper or translucent coloured foils, tied together to form wondrous, graceful shapes. The dangling and floating spheres are visually offset by the standing and reclining forms: in the clearings between the toilet paper and the strings, sculptures are placed that poetically combine standing paper and holding plaster moulds. The toilet paper ends on the floor, on surfaces made of sieved gypsum and pigment powder. The strips run out in these areas, the last, recumbent leaves covered by powder. The edges of the differently coloured areas are framed by crinkled toilet paper. Bath bombs in the form of cake pieces or in a floral design as well as make-up beads are scattered over the coloured ground. These floor works, covering the entire surface, create paths on which we can enter the fantastic landscape entitled “Safety As A Stance”. They also give the room a harmonious pastel palette of colours ranging from pink to peach to beige and yellow. When daylight or sunlight strikes the materials, they glow in their pastel hues and colour the entire ambience. This considerably intensifies the holistic experience of material and colour.

Sometimes we catch a glimpse of ourselves in the room: Under the title “Looking Glass (picture grid)”, Black has panelled the rear long side of the hall with numerous mirrors in the alcoves of the huge lattice windows. Some of the panels are hand-painted, showing markings and colourful gestures on the reflective surface. The doubling of the mirrored images and consequent enlargement of the room has an expansive effect and dissolves the tangible space into fragments.

The Dornbirn exhibition vividly illustrates the great power that Black infuses into her artistic language, which is based on a formal aesthetic understanding of sculpture, that is, on the pure form and effect of the artwork. She says: “My work is essentially formal. Its main interest is aesthetic. […] What goes on in it is the processing and reprocessing of the relationship between colour, form, material and composition.” (Karla Black, Kunstforum International, vol. 227 (2014): 209-210.) The depiction is always abstract, never figurative. Physical representation of the human form is exclusively through the bodily presence of visitors or in her gesturally painted mirror works, whose impasto application of paint or occasional omissions manifest indistinct or fragmented reflections.

The work is abstract not only in terms of what is depicted, but also in terms of the materials chosen and how they are used. This is because no fixed and often no permanent form is given them. For example, if gypsum powder is used, it is not mixed with water to form a hardening mass as usual, but is applied in its original state. It is sieved, layered, dusted over foils and much else besides. The fact that the material could potentially have a fixed form in the next step of the process leaves it in a seemingly unfinished state. This example makes clear that the properties and purpose of materials are linked to directives for their use, directives that Black refuses to carry out. This gives her work a very appealing indeterminacy, a state between raw and finished.

The starting point of all Black’s work is her enjoyment of working with a particular material. The type of material is not important. The palette employs not only traditional art materials, such as acrylic paint, pigment or plaster, but also incorporates any materials from everyday life that serves the purpose, including plastic film, soap, make-up or toilet paper. By contrast, the medium to which Black assigns her work is clearly defined: it is sculpture. In her practice, she also experiments with other genres, and her works are impressive spatial experiences drawing freely and uninhibitedly on painting, installation, environment and performance. But despite her forays into other media, Black’s presentations are always sculpture exhibitions. Playfully but precisely put to the test, anchored in material aesthetics, the boundaries and possibilities of the concept of sculpture are constantly submitted to broader interrogation.

Black creates immersive situations in which the ephemeral fragility of materials such as powder or paper is paired with the strength and durability of the meticulously space-filling formats. In Dornbirn, she combines existing works with new creations and with sculptural strategies and elements that seem familiar from previous productions. This sense of recognition allows us to understand the development and function of the new combination within her elaborated formal-aesthetic approach. The method of production derives from the physical conditions, which include her own state of being as well as the architecture and its spatial specifications. Within this framework, Black primarily responds emotionally, drawing on a realm beyond language, such as unconscious intuition. In a careful process of sifting, layering, piling and heaping, knotting, hanging and smearing her materials, Black gives them form in situ in the exhibition space. The intuitive beginning is accompanied in the next steps by conscious intention, by consideration of those very physical conditions and their final form and effect.

The aesthetic effect – meaning on the one hand beauty, and on the other hand the nature of the materials, the composition of the elements, and the experience and sensory enjoyment of the works – is self-referential and uncompromising, purified of any external meaning, and the most important category. Yet in Dornbirn, we can see that creative references related to content can still play a role: Black’s floor installations create a freedom of movement that allows us to enter into them. The surfaces surrounded by toilet paper look like flowerbeds, and the association with garden designs, in which plantings become elaborate ornamental formations, is no accident. Since the beginning of the project, the partially mirrored windows of the assembly hall have been an integral part of the exhibition. Black herself formulates clear references to garden design and the famous Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. Not only the structure of the assembly hall’s windows resemble the mirrored niches of Versailles – Black’s entire form language and colour choice has also been recognisably influenced by Baroque and Rococo design elements. Their playful aesthetics, with flowing lines, billowing fabrics, asymmetry, pastel tones and nature-inspired motifs, found its way into her work. Abstracting these aspects and combing them with her own vocabulary of materials, Black creates the unique formal language that has made her internationally renowned.

Biography Karla Black was born in 1972 in Alexandria, UK, and lives and works in Glasgow, UK. She represented Scotland at the 57th Venice Biennale (2011) and her work was exhibited at Manifesta 10 at St Petersburg (2014). Her immersive, often site-specific installations have been shown at numerous solo exhibitions, for example at the Bechtler Foundation, Uster (2024), New Art Gallery Walsall (2023), Modern Art Gallery, London (2022), Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh (2021), Des Moines Art Centre (2020), Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt (2019), Le Festival d’Automne, Paris (2017), Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle (2017), Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh (2016), Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (2016), Gemeentemuseum, The Hague (2013), Dallas Museum of Art (2012) and Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow (2012).