Fernando Sánchez Castillo

Tlateloclo... Winter Games

19 Nov 2016 - 04 Feb 2017

Studio Fernando Sánchez Castillo, with the collaboration of Sala Arte Público and Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco - Mermorial 68, 2016

Studio Fernando Sánchez Castillo, with the collaboration of Sala Arte Público and Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco - Mermorial 68, 2016

FERNANDO SÁNCHEZ CASTILLO

Tlateloclo... Winter Games

19 November 2016 - 4 February 2017

With the collaboration of Sala Arte Público Siqueiros and Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco - Memorial 68, Mexico

This solo exhibition by Fernando Sánchez Castillo deals with the tragic events that took place in Tlatelolco on October 2nd, 1968. The works in the show are based on the artist’s investigation into all forms of resource material relating to the massacre—documents, photographs, videos, and archives—and on the artistic re-representation and reenactment of some of these by enhancing and elaborating on their meanings. All of the pieces here have been commissioned and conceived specially for this occasion.

Sánchez Castillo is producing exceptional work regarding the issues behind monumentality. While other artists also address the phenomenon, they have tended to approach it as a subject or a theme by criticizing its content, ironizing its form and esthetic, or even by directly intervening real monuments. Instead Sánchez Castillo develops, often with humor, a radical critique of monuments’ usual discourse in which he disarticulates its agencies of power and representation.

His deconstruction of monuments is, beyond the above mentioned, a means to look into the contradictions of History, of subverting the representations and manipulations of official narratives, of demystifying its canons, heroes, discourses, and established truths. History is his main subject, and he tends to engage with it—as is the case in this occasion—through the documents that have been instrumental for its own construction and representation. The artist has said that he is interested in the “internal history of history” as it is more profound than the versions that have been groomed for public consumption. His work is an attempt to rewrite History’s accounts or at least to make us more aware of its complexities and traces, and to show that History is constructed from a position of power.

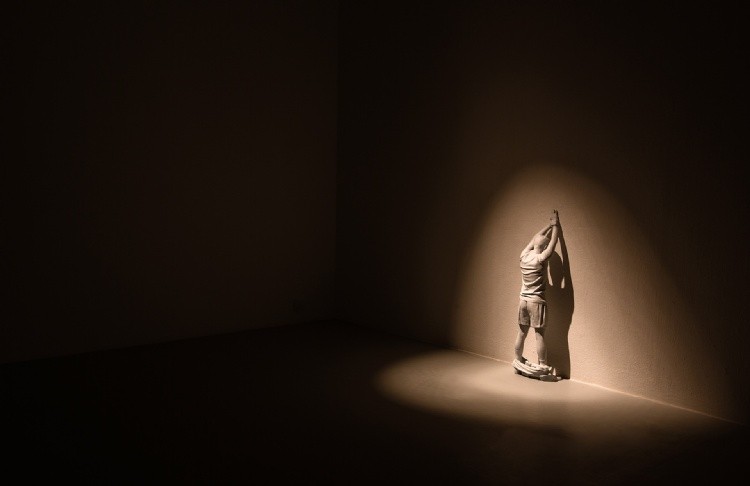

The most spectacular of the pieces constructed for this show is a continuation of his series of monuments to anonymous heroes, a paradoxical canonization of historical figures that have been ignored by hegemonic representation. His best known piece in this series is a colossal statue of Tank Man, the unknown figure who confronted and successfully stopped a column of war tanks next to Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989, just a day after the civilian massacre there. At Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros, the artist presents a great statue –only a centimeter shorter than Michelangelo’s David— of an anonymous student detained at Tlatelolco whose image he borrowed from a photograph of the events. As with Tank Man, this is a statue of a hero whose identity is unknown; his face remains eternally hidden as we only see his back in the infamous photograph. There are various images that document how the detained students in Tlatelolco were forced by the militaries to pull their pants down in order to show that they weren’t armed, humiliating and placing them in a situation of both moral and physical helplessness. The grandiose representation of one of these unnamed students creates an obvious paradoxical friction through the act of monumentalizing a defenseless victim that has been coerced into an embarrassing position instead of elevating a heroe or a leader to glory through victorious poses. This gesture inverts the usual and official commemorative rhetoric. The monument also calls attention to a less stressed, but nonetheless very important fact of Tlatelolco’s repression: the large amount of people that were incarcerated during and after the event.

In the exhibition, the tapestry will show a map of the Plaza de las Tres Culturas where the location of the snipers and the direction of their shots are depicted. The original diagram appeared in between the papers of General Marcelino García Barragán who was the Secretary of Defense during the massacre and whose archives were given, posthumously and following the General’s own wishes, by his family to journalist Julio Scherer. The map documents the actions of the snipers who, thanks to this and other sources, were discovered to be government officials working within the Presidential General Staff and members of the Olympia Battalion. They acted out a secret operation—woven from the highest levels–driven to provoke the army to violently reprehend the students by shooting at both the men in uniform and the protestors. This diagram thus shows the hidden trigger behind the massacre, the center of an even more mysterious plot.

The main piece in this exhibition is a video that shows the flight of a drone over Tlatelolco. It reproduces, drawing from existing documentation, that of a helicopter flying over the site on the day of the events as a sort of fictitious reenactment of history. The video illustrates a luminous action in the Plaza made with green and red flares, imitating the pyrotechnics that signaled the start of military action in 1968 and it culminates with a white light that makes up the symbolic composition of the Mexican flag - a posthumous homage. Forty-three grenades were employed in the making of the video, the same number—according to García Barragán’s documents—of the mortal victims of October 2nd, cipher that in a meaningful coincidence also corresponds with the number of students that disappeared at Ayotzinapa, thus extending tribute to the current victims of a history that moves in circular motion. Other pieces, documents, and images complete this project. Its title alludes to a phrase that was falsely attributed to a TV news commentator, but that has nonetheless remained fixed in the collective imaginary of the massacre as an eloquent figure in the concealments of History.

Tlateloclo... Winter Games

19 November 2016 - 4 February 2017

With the collaboration of Sala Arte Público Siqueiros and Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco - Memorial 68, Mexico

This solo exhibition by Fernando Sánchez Castillo deals with the tragic events that took place in Tlatelolco on October 2nd, 1968. The works in the show are based on the artist’s investigation into all forms of resource material relating to the massacre—documents, photographs, videos, and archives—and on the artistic re-representation and reenactment of some of these by enhancing and elaborating on their meanings. All of the pieces here have been commissioned and conceived specially for this occasion.

Sánchez Castillo is producing exceptional work regarding the issues behind monumentality. While other artists also address the phenomenon, they have tended to approach it as a subject or a theme by criticizing its content, ironizing its form and esthetic, or even by directly intervening real monuments. Instead Sánchez Castillo develops, often with humor, a radical critique of monuments’ usual discourse in which he disarticulates its agencies of power and representation.

His deconstruction of monuments is, beyond the above mentioned, a means to look into the contradictions of History, of subverting the representations and manipulations of official narratives, of demystifying its canons, heroes, discourses, and established truths. History is his main subject, and he tends to engage with it—as is the case in this occasion—through the documents that have been instrumental for its own construction and representation. The artist has said that he is interested in the “internal history of history” as it is more profound than the versions that have been groomed for public consumption. His work is an attempt to rewrite History’s accounts or at least to make us more aware of its complexities and traces, and to show that History is constructed from a position of power.

The most spectacular of the pieces constructed for this show is a continuation of his series of monuments to anonymous heroes, a paradoxical canonization of historical figures that have been ignored by hegemonic representation. His best known piece in this series is a colossal statue of Tank Man, the unknown figure who confronted and successfully stopped a column of war tanks next to Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989, just a day after the civilian massacre there. At Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros, the artist presents a great statue –only a centimeter shorter than Michelangelo’s David— of an anonymous student detained at Tlatelolco whose image he borrowed from a photograph of the events. As with Tank Man, this is a statue of a hero whose identity is unknown; his face remains eternally hidden as we only see his back in the infamous photograph. There are various images that document how the detained students in Tlatelolco were forced by the militaries to pull their pants down in order to show that they weren’t armed, humiliating and placing them in a situation of both moral and physical helplessness. The grandiose representation of one of these unnamed students creates an obvious paradoxical friction through the act of monumentalizing a defenseless victim that has been coerced into an embarrassing position instead of elevating a heroe or a leader to glory through victorious poses. This gesture inverts the usual and official commemorative rhetoric. The monument also calls attention to a less stressed, but nonetheless very important fact of Tlatelolco’s repression: the large amount of people that were incarcerated during and after the event.

In the exhibition, the tapestry will show a map of the Plaza de las Tres Culturas where the location of the snipers and the direction of their shots are depicted. The original diagram appeared in between the papers of General Marcelino García Barragán who was the Secretary of Defense during the massacre and whose archives were given, posthumously and following the General’s own wishes, by his family to journalist Julio Scherer. The map documents the actions of the snipers who, thanks to this and other sources, were discovered to be government officials working within the Presidential General Staff and members of the Olympia Battalion. They acted out a secret operation—woven from the highest levels–driven to provoke the army to violently reprehend the students by shooting at both the men in uniform and the protestors. This diagram thus shows the hidden trigger behind the massacre, the center of an even more mysterious plot.

The main piece in this exhibition is a video that shows the flight of a drone over Tlatelolco. It reproduces, drawing from existing documentation, that of a helicopter flying over the site on the day of the events as a sort of fictitious reenactment of history. The video illustrates a luminous action in the Plaza made with green and red flares, imitating the pyrotechnics that signaled the start of military action in 1968 and it culminates with a white light that makes up the symbolic composition of the Mexican flag - a posthumous homage. Forty-three grenades were employed in the making of the video, the same number—according to García Barragán’s documents—of the mortal victims of October 2nd, cipher that in a meaningful coincidence also corresponds with the number of students that disappeared at Ayotzinapa, thus extending tribute to the current victims of a history that moves in circular motion. Other pieces, documents, and images complete this project. Its title alludes to a phrase that was falsely attributed to a TV news commentator, but that has nonetheless remained fixed in the collective imaginary of the massacre as an eloquent figure in the concealments of History.