Margret

08 Sep - 03 Nov 2012

MARGRET

Chronik einer Affäre

8 September - 3 November 2012

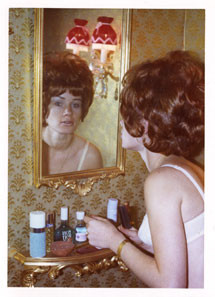

The chronicle of an affair in pictures and texts, the secret diary of a Cologne business owner, from 1970, is exhibited for the first time here after more than forty years. This is a voyeuristic text/image collage which, in spite of dinner chits and hotel bills, of postcards and hair samples, is not presented in a historical museum or archive, but in an art institution. Yet what is this text-picture rapport? Is it outsider art, amateur art, or, as story art used to be in those days, just another way of hanging out around the genre corners of art? No doubt, the story about Margret is a report moving along the edges of art and only many years after the fact can be taken as art.

It is not an outsider, but an obsessed person who auto-voyeuristically keeps tab here on sexual encounters, places, dates, on what the woman wears, on the clothes he buys for her, on the hotels, restaurants, and what they ate and drank. After closing time, between three and five p.m., Günter (39) makes love to Margret (24) in the usual way, missionary style. For the day after, the entry simply reads: "Ate devilled salad." Margret works as a secretary in Günter's company. Both are married. Everything is top secret, or so Günter believes. It all begins with photographs, with empty boxes of contraceptives, with chits from expensive restaurants and short notices. In September 1970, the diary entries set in, with precise descriptions of what happens during foreplay and then of the sexual act itself, but also mentioning all kinds of things happening besides. All this is meticulously typed, in red and black ink, as by a bookkeeper of his own obsession. The couple go on "business trips" in Günter's Opel Kapitän, stay at spa hotels and visit the casino in Wiesbaden. Then the trysts begin to take place in an attic flat in Günter's store building. Nobody is supposed to know, but people must notice something. Margret prepares roulades and redfish filets with cucumber salad. They drink Cappy (orange juice) with a green shot (Escorial, strong liquor) and watch "colourful television." Margret dresses for him in the clothes he has bought her. He, the perfect lover, in truth is a macho man who wants to have everything under control. She enjoys his attention, his generosity, is happy to let herself be manipulated, is jealous, becomes pregnant despite the pills, and has an illegal abortion − for the third time in her young life. Just before Christmas 1970 the reports and photographs break off. The relationship appears to be at an end. Margret is scared. She tells him that "after Christmas the fucking will be over and you will not dance at two weddings anymore." He gets involved with other women. These are no love stories, though, just obsessive sexual romps, chronicled nonetheless in hundreds of grotesque documents testifying to the stuffy German milieu in the early years of the Kohl era.

We are grateful to Siegfried Sander, Hamburg, for readily putting the documents at our disposal. A book will appear to go with the exhibition, that will subsequently travel to KW Berlin, published by Nicole Delmes and Susanne Zander, with texts by Veit Loers and Susanne Pfeffer, at Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König.

Chronik einer Affäre

8 September - 3 November 2012

The chronicle of an affair in pictures and texts, the secret diary of a Cologne business owner, from 1970, is exhibited for the first time here after more than forty years. This is a voyeuristic text/image collage which, in spite of dinner chits and hotel bills, of postcards and hair samples, is not presented in a historical museum or archive, but in an art institution. Yet what is this text-picture rapport? Is it outsider art, amateur art, or, as story art used to be in those days, just another way of hanging out around the genre corners of art? No doubt, the story about Margret is a report moving along the edges of art and only many years after the fact can be taken as art.

It is not an outsider, but an obsessed person who auto-voyeuristically keeps tab here on sexual encounters, places, dates, on what the woman wears, on the clothes he buys for her, on the hotels, restaurants, and what they ate and drank. After closing time, between three and five p.m., Günter (39) makes love to Margret (24) in the usual way, missionary style. For the day after, the entry simply reads: "Ate devilled salad." Margret works as a secretary in Günter's company. Both are married. Everything is top secret, or so Günter believes. It all begins with photographs, with empty boxes of contraceptives, with chits from expensive restaurants and short notices. In September 1970, the diary entries set in, with precise descriptions of what happens during foreplay and then of the sexual act itself, but also mentioning all kinds of things happening besides. All this is meticulously typed, in red and black ink, as by a bookkeeper of his own obsession. The couple go on "business trips" in Günter's Opel Kapitän, stay at spa hotels and visit the casino in Wiesbaden. Then the trysts begin to take place in an attic flat in Günter's store building. Nobody is supposed to know, but people must notice something. Margret prepares roulades and redfish filets with cucumber salad. They drink Cappy (orange juice) with a green shot (Escorial, strong liquor) and watch "colourful television." Margret dresses for him in the clothes he has bought her. He, the perfect lover, in truth is a macho man who wants to have everything under control. She enjoys his attention, his generosity, is happy to let herself be manipulated, is jealous, becomes pregnant despite the pills, and has an illegal abortion − for the third time in her young life. Just before Christmas 1970 the reports and photographs break off. The relationship appears to be at an end. Margret is scared. She tells him that "after Christmas the fucking will be over and you will not dance at two weddings anymore." He gets involved with other women. These are no love stories, though, just obsessive sexual romps, chronicled nonetheless in hundreds of grotesque documents testifying to the stuffy German milieu in the early years of the Kohl era.

We are grateful to Siegfried Sander, Hamburg, for readily putting the documents at our disposal. A book will appear to go with the exhibition, that will subsequently travel to KW Berlin, published by Nicole Delmes and Susanne Zander, with texts by Veit Loers and Susanne Pfeffer, at Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König.