Daniel Guzmán

24 Mar - 09 May 2015

DANIEL GUZMÁN

death never takes a vacation

24 March – 9 May 2015

“Existence is not something which lets itself be thought of from a distance; it must invade you suddenly, master you, weigh heavily on your heart like a great motionless beast – or else there is nothing at all.”

Jean-Paul Sartre

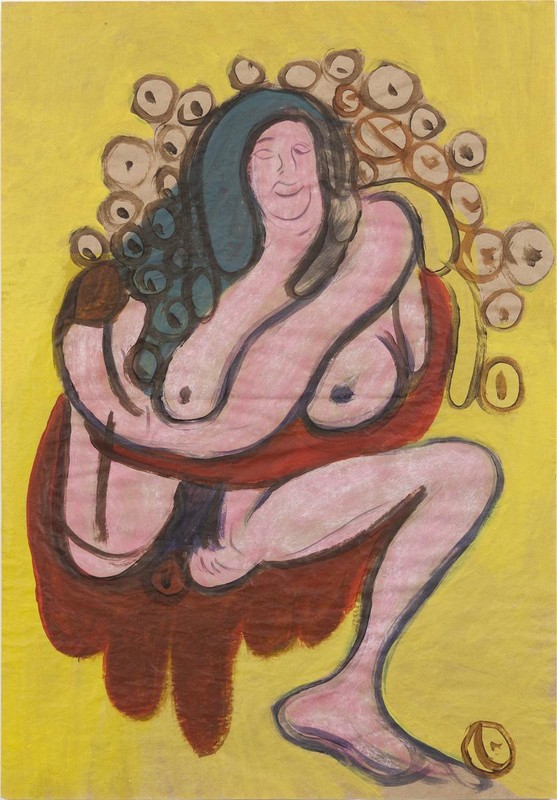

Daniel Guzmán’s (Mexico, 1964) work is the result of a constant and disciplined investigation guided by the hand’s intuition, which translates the artist’s imagination and gives it solid form on paper. Death Never Takes a Vacation stems from Guzmán’s fascination with Aztec iconography, in particular the earth goddesses, who embody the dualities of fertility and death, life, and sacrifice.

The exhibition features more than 100 drawings from the Chromosome Damage series, in which representations of Pre Hispanic deities such as Coatlicue and Tlaltecuhtli parade along with human figures, beasts with masks, and demons. These images on paper reveal an uncontrolled process of metamorphosis: arms, nipples, snakes, claws and hair sprout from forms rendered not without a touch of humour. According to the poet Rubén Bonifaz Nuño, “Coatlicue is a force, an energy on the verge of overflowing to create the universe.” This way of conceiving creation is similar to the scientific explanations that posit the universe was formed by the Big Bang, and that everything is made of the same molecules resulting from this explosion. For Guzmán, this means we are part of the meteorites and the stars, as well as more prosaic matter, like shit.

Guzmán’s drawings break down and come alive before the viewer, who, like Sartre’s protagonist in Nausea, discovers to his dismay “the diversity of things, their individuality, were only an appearance, a varnish. Once the varnish melts, it leaves only “soft, monstrous lumps, in naked disorder, with a frightful and obscene nakedness.” The sensual and the grotesque are present in equal measure in Guzmán’s work: the influence of Matisse’s nudes and Willem de Kooning’s portraits of women recombine in hybrid figures who echo Hermelinda Linda and the disturbing cartoons of Basil Wolverton.

The forms in Chromosome Damage seem to sprout from one another, the product of a dialog between Pre Hispanic archaeology and pop culture. They are infused with strains of José Clemente Orozco and the paintings of Chucho Reyes, or even the musical compositions of Reverend Gary Davis, whose 1960 recording of “Death Don’t Have No Mercy” inspired the title of the show. Guzmán’s drawings encompass all of these references, however, he never insists that the viewer decrypt and analyze the origins of each element. Rather, this richness and diversity of source material permits the work to transcend its cultural specificity and speak for itself.

This series represents a fresh interest in color. In comparison to earlier drawings, which are predominantly executed in ink and pencil on white surfaces such as paper or walls, these figures inhabit a neutral space governed by simple organic palette. Made with pastels, charcoal, and acrylic paint, each drawing uses no more than two or three colors, the vast majority of which are earth tones. Reds, browns, yellows and pinks coexist effortlessly on the butcher paper, a recycled paper commonly used for wrapping merchandise in the markets. These materials lend plasticity to the forms, which are rendered with rough strokes that eschew aesthetic pretense and preciousness.

n contrast to his earlier works, characterized by the inclusion of quotes from writers such as Roberto Bolaño and William Burroughs, or song lyrics from rock and punk groups, the characters in Chromosome Damage have their own lives and their own voices. They rebel against the viewer’s static gaze with bodies that seem unfinished, in the process of becoming. The medium format of the drawings allows the viewer to absorb the totality of the composition and submerge themselves in an image that inspires fear, respect, occasional laughter; one that unfolds and comes together again between voluptuous curves, tongues, and tentacles with eyes that multiply with unbridled abundance. More than illustrating an error in cellular reproduction, for Guzmán “these drawings seek to represent how the universe is deformed, how matter dissolves and bends in order to recombine in front of our eyes.”

Daniel Guzmán received his B.F.A in Visual Arts from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. He has shown his work in solo exhibitions at the Drawing Room, London, United Kingdom; Museo de Arte de Zapopan, Mexico; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Oaxaca, Mexico, New Museum, New York, United States; Museo Universitario de Ciencias y Arte MUCA, Mexico. His work has been presented at the following biennials: 5th Berlin Biennial, the 55th Carnegie International and the 50th Venice Biennial.

Guzmán lives and works in Mexico City.

death never takes a vacation

24 March – 9 May 2015

“Existence is not something which lets itself be thought of from a distance; it must invade you suddenly, master you, weigh heavily on your heart like a great motionless beast – or else there is nothing at all.”

Jean-Paul Sartre

Daniel Guzmán’s (Mexico, 1964) work is the result of a constant and disciplined investigation guided by the hand’s intuition, which translates the artist’s imagination and gives it solid form on paper. Death Never Takes a Vacation stems from Guzmán’s fascination with Aztec iconography, in particular the earth goddesses, who embody the dualities of fertility and death, life, and sacrifice.

The exhibition features more than 100 drawings from the Chromosome Damage series, in which representations of Pre Hispanic deities such as Coatlicue and Tlaltecuhtli parade along with human figures, beasts with masks, and demons. These images on paper reveal an uncontrolled process of metamorphosis: arms, nipples, snakes, claws and hair sprout from forms rendered not without a touch of humour. According to the poet Rubén Bonifaz Nuño, “Coatlicue is a force, an energy on the verge of overflowing to create the universe.” This way of conceiving creation is similar to the scientific explanations that posit the universe was formed by the Big Bang, and that everything is made of the same molecules resulting from this explosion. For Guzmán, this means we are part of the meteorites and the stars, as well as more prosaic matter, like shit.

Guzmán’s drawings break down and come alive before the viewer, who, like Sartre’s protagonist in Nausea, discovers to his dismay “the diversity of things, their individuality, were only an appearance, a varnish. Once the varnish melts, it leaves only “soft, monstrous lumps, in naked disorder, with a frightful and obscene nakedness.” The sensual and the grotesque are present in equal measure in Guzmán’s work: the influence of Matisse’s nudes and Willem de Kooning’s portraits of women recombine in hybrid figures who echo Hermelinda Linda and the disturbing cartoons of Basil Wolverton.

The forms in Chromosome Damage seem to sprout from one another, the product of a dialog between Pre Hispanic archaeology and pop culture. They are infused with strains of José Clemente Orozco and the paintings of Chucho Reyes, or even the musical compositions of Reverend Gary Davis, whose 1960 recording of “Death Don’t Have No Mercy” inspired the title of the show. Guzmán’s drawings encompass all of these references, however, he never insists that the viewer decrypt and analyze the origins of each element. Rather, this richness and diversity of source material permits the work to transcend its cultural specificity and speak for itself.

This series represents a fresh interest in color. In comparison to earlier drawings, which are predominantly executed in ink and pencil on white surfaces such as paper or walls, these figures inhabit a neutral space governed by simple organic palette. Made with pastels, charcoal, and acrylic paint, each drawing uses no more than two or three colors, the vast majority of which are earth tones. Reds, browns, yellows and pinks coexist effortlessly on the butcher paper, a recycled paper commonly used for wrapping merchandise in the markets. These materials lend plasticity to the forms, which are rendered with rough strokes that eschew aesthetic pretense and preciousness.

n contrast to his earlier works, characterized by the inclusion of quotes from writers such as Roberto Bolaño and William Burroughs, or song lyrics from rock and punk groups, the characters in Chromosome Damage have their own lives and their own voices. They rebel against the viewer’s static gaze with bodies that seem unfinished, in the process of becoming. The medium format of the drawings allows the viewer to absorb the totality of the composition and submerge themselves in an image that inspires fear, respect, occasional laughter; one that unfolds and comes together again between voluptuous curves, tongues, and tentacles with eyes that multiply with unbridled abundance. More than illustrating an error in cellular reproduction, for Guzmán “these drawings seek to represent how the universe is deformed, how matter dissolves and bends in order to recombine in front of our eyes.”

Daniel Guzmán received his B.F.A in Visual Arts from the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. He has shown his work in solo exhibitions at the Drawing Room, London, United Kingdom; Museo de Arte de Zapopan, Mexico; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Oaxaca, Mexico, New Museum, New York, United States; Museo Universitario de Ciencias y Arte MUCA, Mexico. His work has been presented at the following biennials: 5th Berlin Biennial, the 55th Carnegie International and the 50th Venice Biennial.

Guzmán lives and works in Mexico City.