Alex Olson

14 Feb 2016

ALEX OLSON

Scene of Elastic Sight

22 May – 19 July 2015

My eyes have been giving me trouble for several years now. Pesky eyes. I didn’t know I needed glasses until high school when another student lent me hers. Before then, I assumed everyone saw as I did. Why would you imagine that others see what you cannot?

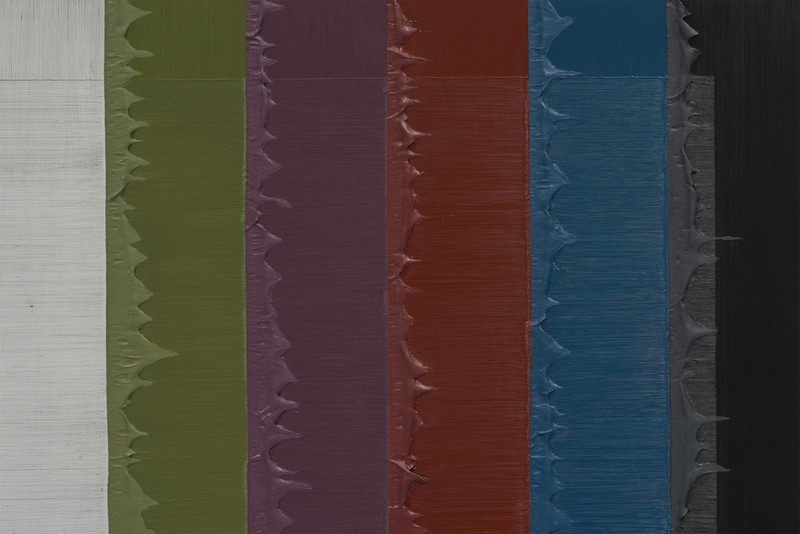

This exhibition circulates around an expanded idea of sight and considers how vision occurs beyond the eyes alone. Each painting embodies a different experience of seeing: physically, psychologically and environmentally as well as through projection, choice, and belief systems.

Sometimes I lose vision in one eye. It turns me into a Cyclops. While annoying at times, it’s also fascinating and creates for exciting although unwanted moments in which clarity appears and disappears with a blink of an eye.

Mirroring, echoing, and reiteration occur throughout the course of the exhibition to extend the conversation within one painting onto the next.

I asked a friend why she thought there are so many portraits of artists with one eye open and one eye closed or covered. She said she believed there’s a history of portraiture of seers and thinkers with this pose, as they are looking both within and out simultaneously. She cited a portrait of the mathematician Euler as an example. Later she found out that he was painted with one eye closed simply because he had eye problems.

An intimately scaled diptych Blink, with one canvas painted with eyes closed and the other with eyes open, considers sight as an elongated line of vision with both an interior and an exterior gaze.

I recently went to a yard sale where I picked up a small metal plaque with eyes embossed on it. Apparently, it’s a votive and can be offered to a saint in exchange for improved vision.

Wayfinder (Day) and Wayfinder (Dusk) in the form of clock-compass-sundials signal towards second glances and propose a continuous loop. Channel (1) and Channel (2) present simultaneous imagery with an impossibility of focus.

Ironically, the author of The Doors of Perception Aldous Huxley had terrible eyesight. He was left nearly blind by a disease at 16, but regained some vision and claims to have improved it further using the Bates Method, an unorthodox form of visual education that emphasizes a mind-body connection. In his book The Art of Seeing, Huxley champions his success with this method while dismissing traditional optometry practices and provides thorough details for visual exercises, including swinging the body, palming the eyes, and sunning. [1]

Slide and Reflect look at graphic versus physical signs, appearing in constant flux as the viewer moves in front and to the sides of work. For Better Insight and For Better Eyesight promise improved vision through engagement. Finally, Screen calls upon the viewer’s imagination, as a cover of brush-stroke waves encloses and obscures a composition of chalked cast shadows.

I heard a podcast about a blind man who can navigate with echolocation, like a bat. A neuroscientist conducted a study with him in which they recorded his echolocation of certain objects in space and then played it back to him while scanning his brain. Surprisingly, his visual cortex was active in certain areas as it would be for so-called sighted people looking at the same objects. He can in effect “see” images, which leads to the conclusion that you do not need eyes for sight. [2]

These are active paintings and best experienced through multiple rotations around the space. Changing sightlines prompt new perspectives, highlighting and stretching the pathways in which vision takes form.

[1] Aldous Huxley, The Art of Seeing (1942; reprint Berkeley: Creative Arts Book Company, 1982).

[2] “Batman, Part 2,” hosted by Lulu Miller and Alix Spiegel, Invisibilia, NPR, January 23, 2015, http://www.npr.org/programs/invisibilia/378577902/how-to-become-batman

Alex Olson lives and works in Los Angeles. She received a BA from Harvard University in 2001, and an MFA from CalArts in 2008. Her work has been featured in exhibitions: “Variations: Conversations in and Around Abstract Painting”, curated by Nancy Meyer and Franklin Sirmans, LACMA, Los Angeles; “Reductive Minimalism”, curated by Erica Barrish, University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor (2014); “The Stand In (Or a Glass of Milk)”, curated by Alexandra Gaty and Lauren Mackler, Public Fiction, Los Angeles; “Murmurs: Recent Contemporary Acquisitions”, curated by Rita Gonzalez, LACMA, Los Angeles; “Painter, Painter”, curated by Eric Crosby and Bartholomew Ryan, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (all 2013) and “Made in LA”, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2012). “Scene of Elastic Sight” is Alex Olson’s second solo exhibition with the gallery.

Scene of Elastic Sight

22 May – 19 July 2015

My eyes have been giving me trouble for several years now. Pesky eyes. I didn’t know I needed glasses until high school when another student lent me hers. Before then, I assumed everyone saw as I did. Why would you imagine that others see what you cannot?

This exhibition circulates around an expanded idea of sight and considers how vision occurs beyond the eyes alone. Each painting embodies a different experience of seeing: physically, psychologically and environmentally as well as through projection, choice, and belief systems.

Sometimes I lose vision in one eye. It turns me into a Cyclops. While annoying at times, it’s also fascinating and creates for exciting although unwanted moments in which clarity appears and disappears with a blink of an eye.

Mirroring, echoing, and reiteration occur throughout the course of the exhibition to extend the conversation within one painting onto the next.

I asked a friend why she thought there are so many portraits of artists with one eye open and one eye closed or covered. She said she believed there’s a history of portraiture of seers and thinkers with this pose, as they are looking both within and out simultaneously. She cited a portrait of the mathematician Euler as an example. Later she found out that he was painted with one eye closed simply because he had eye problems.

An intimately scaled diptych Blink, with one canvas painted with eyes closed and the other with eyes open, considers sight as an elongated line of vision with both an interior and an exterior gaze.

I recently went to a yard sale where I picked up a small metal plaque with eyes embossed on it. Apparently, it’s a votive and can be offered to a saint in exchange for improved vision.

Wayfinder (Day) and Wayfinder (Dusk) in the form of clock-compass-sundials signal towards second glances and propose a continuous loop. Channel (1) and Channel (2) present simultaneous imagery with an impossibility of focus.

Ironically, the author of The Doors of Perception Aldous Huxley had terrible eyesight. He was left nearly blind by a disease at 16, but regained some vision and claims to have improved it further using the Bates Method, an unorthodox form of visual education that emphasizes a mind-body connection. In his book The Art of Seeing, Huxley champions his success with this method while dismissing traditional optometry practices and provides thorough details for visual exercises, including swinging the body, palming the eyes, and sunning. [1]

Slide and Reflect look at graphic versus physical signs, appearing in constant flux as the viewer moves in front and to the sides of work. For Better Insight and For Better Eyesight promise improved vision through engagement. Finally, Screen calls upon the viewer’s imagination, as a cover of brush-stroke waves encloses and obscures a composition of chalked cast shadows.

I heard a podcast about a blind man who can navigate with echolocation, like a bat. A neuroscientist conducted a study with him in which they recorded his echolocation of certain objects in space and then played it back to him while scanning his brain. Surprisingly, his visual cortex was active in certain areas as it would be for so-called sighted people looking at the same objects. He can in effect “see” images, which leads to the conclusion that you do not need eyes for sight. [2]

These are active paintings and best experienced through multiple rotations around the space. Changing sightlines prompt new perspectives, highlighting and stretching the pathways in which vision takes form.

[1] Aldous Huxley, The Art of Seeing (1942; reprint Berkeley: Creative Arts Book Company, 1982).

[2] “Batman, Part 2,” hosted by Lulu Miller and Alix Spiegel, Invisibilia, NPR, January 23, 2015, http://www.npr.org/programs/invisibilia/378577902/how-to-become-batman

Alex Olson lives and works in Los Angeles. She received a BA from Harvard University in 2001, and an MFA from CalArts in 2008. Her work has been featured in exhibitions: “Variations: Conversations in and Around Abstract Painting”, curated by Nancy Meyer and Franklin Sirmans, LACMA, Los Angeles; “Reductive Minimalism”, curated by Erica Barrish, University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor (2014); “The Stand In (Or a Glass of Milk)”, curated by Alexandra Gaty and Lauren Mackler, Public Fiction, Los Angeles; “Murmurs: Recent Contemporary Acquisitions”, curated by Rita Gonzalez, LACMA, Los Angeles; “Painter, Painter”, curated by Eric Crosby and Bartholomew Ryan, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (all 2013) and “Made in LA”, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2012). “Scene of Elastic Sight” is Alex Olson’s second solo exhibition with the gallery.