Rosemarie Trockel / Thea Djordjadze

12 Nov 2024 - 27 Apr 2025

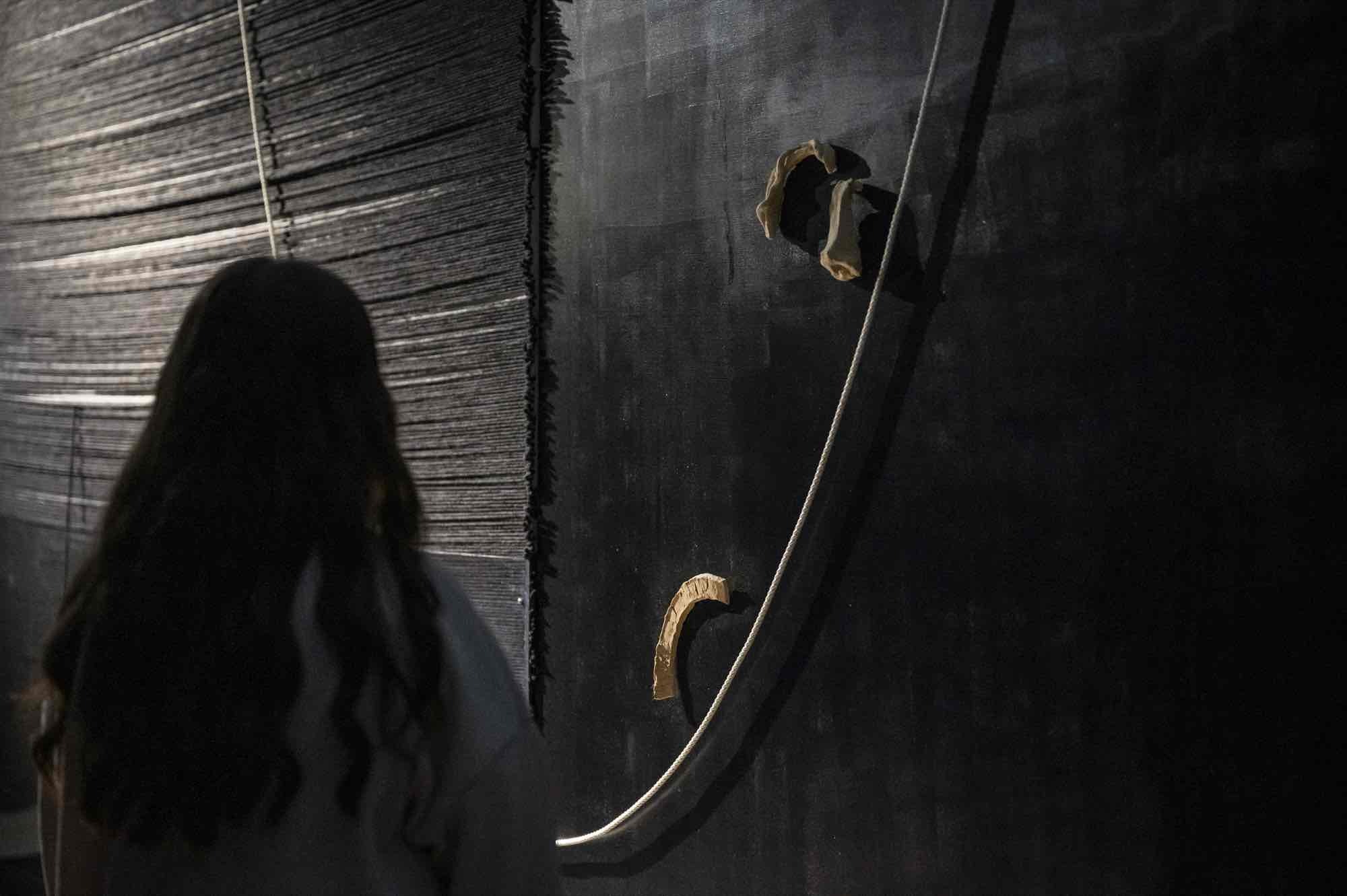

Installation Shot, Rosemarie Trockel / Thea Djordjadze. limitation of life, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhaus

Installation Shot, Rosemarie Trockel / Thea Djordjadze. limitation of life, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhaus

Installation Shot, Rosemarie Trockel / Thea Djordjadze. limitation of life, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhaus

Installation Shot, Rosemarie Trockel / Thea Djordjadze. limitation of life, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhaus

The Lenbachhaus presents a joint exhibition by Rosemarie Trockel (b. Schwerte, Germany, 1952) and Thea Djordjadze (b. Tbilisi, 1971). The two artists forged a close creative relationship between 1998 and 2001, when Djordjadze was Trockel’s student at the Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts, and have realized joint projects before. Their oeuvres explore themes that are relevant to contemporary art and its production, scrutinizing, for example, the creative process and interrogating its premises, traditions, freedoms, and constraints. Meanwhile, they play with the conventions of art and the exhibition space.

In their exhibition "limitation of life", Trockel and Djordjadze weave these themes together: taking inspiration from the poet Arthur Rimbaud’s reflections, they study the idea of beauty and question established aesthetic strategies. The opening lines of Rimbaud’s "Une saison en enfer" (1873) outline what the two artists’ approach is about: "One evening, I sat Beauty down on my knees—and I found her bitter.—And I insulted her."

Trockel and Djordjadze challenge our ingrained habits of perception and the routine operation of our senses: in "limitation of life", they lead us into a darkened room that appears mysterious and at first sight offers no definite clues as to what is going on. Once our eyes have adapted to the dim lighting and we step a bit deeper into the room, visual anchors gradually emerge from the dark and provide some orientation: neon lights, strings, canvases, woolen yarn, and a water basin. Although these objects are familiar, their unwonted assemblage confronts us with the need to see and think anew. The meaning that the individual components have for us is revalued and recontextualized by their transformative modification: the artists have taken neon tubes of the sort that typically bathe the White Cubes in which contemporary art is displayed in bright light and shaped them into sculptural illuminants and (art) objects in their own right; strings extend above our heads like a guidance system or a linear drawing in space; wool, a material associated with a ‘feminine’ and ‘domestic’ craft, has become an art supply; the shaped canvases have become detached from the walls, standing upright in a metal basin filled with water. As suggested by Rimbaud, an established idea of beauty—in this instance, the contemporary aesthetic of museums and exhibitions—is taken apart into its individual components, rethought from the ground up, and combined with elements that are considered unconventional in the museum context.

In "limitation of life", Trockel and Djordjadze merge their styles, but without abandoning their individual creative vocabularies: it is Trockel, for example, who introduces the textile elements. She was among the first women artists in Germany to grapple with gendered stereotypes using materials with ‘feminine’ connotations like wool. In 2000, she presented a solo exhibition in the Lenbachhaus’s Kunstbau venue that gathered her stovetop, knitted, and wool pictures. Djordjadze’s work examines the abstract geometric shapes and materials of postmodernism and conceptual art. She is best known for sculptural objects made out of metal. In the exhibition, her fascination with this material is reflected in elements like the metal water basin that serves as an unusual pedestal for the canvases. Trockel’s wool pictures are joined on it by large-format works on canvas by Djordjadze—paintings on this scale are rare in the artist’s output.

The interplay between Trockel’s and Djordjadze’s creative reflections engenders a space that defies the established conventions of the exhibition business and is meant to be experienced not primarily through the prism of (art-historical) knowledge but on a sensual and intuitive level. The distinctions between audience, setting, and work are blurred; the hierarchy of work and beholder is dismantled. Objects and their functions and meanings are extricated from their agreed-upon arrangement and reassembled with a creative gesture. The conceptual frameworks and models of art history become inoperative, norms concerning what happens at the museum are suspended; the break with obligatory standards and rationality is evident. What comes to the fore instead is intuition. As beholders, we are prodded to jettison our systems of reference and preconceived ideas and to enter a novel and individual edifice of associations in which we can experience the exhibition space, its contents, and its effect on us afresh.

Curated by Eva Huttenlauch

Assistant Curator Nicholas Maniu

In their exhibition "limitation of life", Trockel and Djordjadze weave these themes together: taking inspiration from the poet Arthur Rimbaud’s reflections, they study the idea of beauty and question established aesthetic strategies. The opening lines of Rimbaud’s "Une saison en enfer" (1873) outline what the two artists’ approach is about: "One evening, I sat Beauty down on my knees—and I found her bitter.—And I insulted her."

Trockel and Djordjadze challenge our ingrained habits of perception and the routine operation of our senses: in "limitation of life", they lead us into a darkened room that appears mysterious and at first sight offers no definite clues as to what is going on. Once our eyes have adapted to the dim lighting and we step a bit deeper into the room, visual anchors gradually emerge from the dark and provide some orientation: neon lights, strings, canvases, woolen yarn, and a water basin. Although these objects are familiar, their unwonted assemblage confronts us with the need to see and think anew. The meaning that the individual components have for us is revalued and recontextualized by their transformative modification: the artists have taken neon tubes of the sort that typically bathe the White Cubes in which contemporary art is displayed in bright light and shaped them into sculptural illuminants and (art) objects in their own right; strings extend above our heads like a guidance system or a linear drawing in space; wool, a material associated with a ‘feminine’ and ‘domestic’ craft, has become an art supply; the shaped canvases have become detached from the walls, standing upright in a metal basin filled with water. As suggested by Rimbaud, an established idea of beauty—in this instance, the contemporary aesthetic of museums and exhibitions—is taken apart into its individual components, rethought from the ground up, and combined with elements that are considered unconventional in the museum context.

In "limitation of life", Trockel and Djordjadze merge their styles, but without abandoning their individual creative vocabularies: it is Trockel, for example, who introduces the textile elements. She was among the first women artists in Germany to grapple with gendered stereotypes using materials with ‘feminine’ connotations like wool. In 2000, she presented a solo exhibition in the Lenbachhaus’s Kunstbau venue that gathered her stovetop, knitted, and wool pictures. Djordjadze’s work examines the abstract geometric shapes and materials of postmodernism and conceptual art. She is best known for sculptural objects made out of metal. In the exhibition, her fascination with this material is reflected in elements like the metal water basin that serves as an unusual pedestal for the canvases. Trockel’s wool pictures are joined on it by large-format works on canvas by Djordjadze—paintings on this scale are rare in the artist’s output.

The interplay between Trockel’s and Djordjadze’s creative reflections engenders a space that defies the established conventions of the exhibition business and is meant to be experienced not primarily through the prism of (art-historical) knowledge but on a sensual and intuitive level. The distinctions between audience, setting, and work are blurred; the hierarchy of work and beholder is dismantled. Objects and their functions and meanings are extricated from their agreed-upon arrangement and reassembled with a creative gesture. The conceptual frameworks and models of art history become inoperative, norms concerning what happens at the museum are suspended; the break with obligatory standards and rationality is evident. What comes to the fore instead is intuition. As beholders, we are prodded to jettison our systems of reference and preconceived ideas and to enter a novel and individual edifice of associations in which we can experience the exhibition space, its contents, and its effect on us afresh.

Curated by Eva Huttenlauch

Assistant Curator Nicholas Maniu