Linder

16 Apr - 30 May 2008

LINDER

"She climbs the European Sky"

April 16 – May 30, 2008

Through the keyhole

- the observer catches the sight of something tremendous. His curiosity enforces a bent attitude, as if humbled by everything he can see only because of his impudent voyeurism. This figure of the unobserved has been fascinating in art at least since the renaissance of Greek myths.

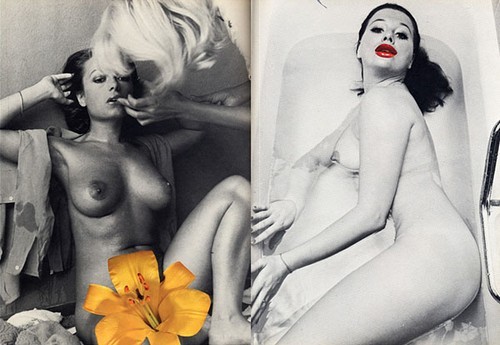

Through the keyhole we see a world without Linder. Only rarely has she been in the narrow focus of its acute-angled perspective, while at the same time since the mid-1970s she has continuously left her traces. A significant figure of the Manchester Punk (and Post-Punk) scene. Punk in England, however, did not have any effect on high art, and in contrast to Germany, here the art ended up, at best, on record sleeves or posters, or it could lead to a career as a graphic artist. Consequently, Linder’s early collages and performances earned her a certain status within pop iconography. Her continuation of the work of Hannah Höch and her references to topical feminist discourses did not matter much in this context. Linder’s band Ludus with its unique experiments in Jazz, too, remained suspended in an iridescent, yet silent interlude – until suddenly, the years between 1976 and ’83 appeared in the centre of the keyhole:

The rediscovery (initiated by her exhibition “The Lives of Women Drawing” at Futura, Prague) did not lead to strict legend building, because Linder had been producing continuously, developing the technical precision of her early work into a lightness of precise combinations on the way in which found magazines, photography collections or drawings work as objets trouvé as well as accord to the principles of Appropriation Art. Her interstice created by manipulation is less a space of reference than a source of immediate action:

“What Linder Saw”

- now allows Linder to look through the keyhole. The title refers to a Mutoscope sequence of images entitled “What the Butler Saw”. This perfect flip-book from the early days of cinematographic machines presented the Butler’s gaze onto a woman undressing. A little lascivious soft-porn from the last but one turn of the century. The enticement of its lewd indiscretion is the secret power – it ends with its revelation. Actaion’s silent communication with Diana led to his (ultimately tragic) transformation and to yet another exchange of power relations. Nothing else is at work in these now speechless drawings that Linder examines for hidden meanings. What she saw is the new communication within a disturbing scenario. A single, precise manipulation (executed with the technical skill of a humorous punch-line) dissolves supposed clichés and transforms them into aggressive aesthetics. Showing what one saw describes a mode which, in Linder’s case, combines performance and collage. The publicized view, seen as “being trapped”, as a trap snapping shut. In its success, Punk never was immediate, but it split up accustomed perspectives. Not in service of a determinate agitation of discursive criticism, but as a free domain within the ordinary. That such interventions are understood does not make them simpler – on the contrary!

Oliver Tepel

"She climbs the European Sky"

April 16 – May 30, 2008

Through the keyhole

- the observer catches the sight of something tremendous. His curiosity enforces a bent attitude, as if humbled by everything he can see only because of his impudent voyeurism. This figure of the unobserved has been fascinating in art at least since the renaissance of Greek myths.

Through the keyhole we see a world without Linder. Only rarely has she been in the narrow focus of its acute-angled perspective, while at the same time since the mid-1970s she has continuously left her traces. A significant figure of the Manchester Punk (and Post-Punk) scene. Punk in England, however, did not have any effect on high art, and in contrast to Germany, here the art ended up, at best, on record sleeves or posters, or it could lead to a career as a graphic artist. Consequently, Linder’s early collages and performances earned her a certain status within pop iconography. Her continuation of the work of Hannah Höch and her references to topical feminist discourses did not matter much in this context. Linder’s band Ludus with its unique experiments in Jazz, too, remained suspended in an iridescent, yet silent interlude – until suddenly, the years between 1976 and ’83 appeared in the centre of the keyhole:

The rediscovery (initiated by her exhibition “The Lives of Women Drawing” at Futura, Prague) did not lead to strict legend building, because Linder had been producing continuously, developing the technical precision of her early work into a lightness of precise combinations on the way in which found magazines, photography collections or drawings work as objets trouvé as well as accord to the principles of Appropriation Art. Her interstice created by manipulation is less a space of reference than a source of immediate action:

“What Linder Saw”

- now allows Linder to look through the keyhole. The title refers to a Mutoscope sequence of images entitled “What the Butler Saw”. This perfect flip-book from the early days of cinematographic machines presented the Butler’s gaze onto a woman undressing. A little lascivious soft-porn from the last but one turn of the century. The enticement of its lewd indiscretion is the secret power – it ends with its revelation. Actaion’s silent communication with Diana led to his (ultimately tragic) transformation and to yet another exchange of power relations. Nothing else is at work in these now speechless drawings that Linder examines for hidden meanings. What she saw is the new communication within a disturbing scenario. A single, precise manipulation (executed with the technical skill of a humorous punch-line) dissolves supposed clichés and transforms them into aggressive aesthetics. Showing what one saw describes a mode which, in Linder’s case, combines performance and collage. The publicized view, seen as “being trapped”, as a trap snapping shut. In its success, Punk never was immediate, but it split up accustomed perspectives. Not in service of a determinate agitation of discursive criticism, but as a free domain within the ordinary. That such interventions are understood does not make them simpler – on the contrary!

Oliver Tepel