Luis Claramunt

13 Jul - 21 Oct 2012

LUIS CLARAMUNT

The Vertical Journey

13 July - 21 October 2012

I don't see any difference between figurative and abstract painting, because painting is, in itself, the image of a reality. A brushstroke can be anything: an insect, a letter, a person. When you create an abstract painting you also start from a particular reality, and then imagination and memory start to work, and that's a reality that is as tangible as any other. Luis Claramunt, El País (5 May, 2000)

The exhibition Luis Claramunt. El viaje vertical features a broad selection of works – including paintings, drawings, photographs and books – produced by the artist from the early seventies to the late nineties. Although Luis Claramunt (Barcelona, 1951 – Zarautz, 2000) is known almost exclusively for his work as a painter, this exhibition presents an entire cosmology that is complex but also unified and consistent, based on his drawing series, his photographic series and his self-published books, which complement and his pictorial work and go beyond it.

Official opening: 12 July 2012. Dates: 13 July – 21 October 2012. Curator: Nuria Enguita Mayo. Organised and produced by: Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA).

1. 1970-1984

Claramunt began his painting career in the late sixties in Barcelona, where he lived on and around Las Ramblas at a time when this iconic promenade was packed with creative potential and had become a stage for radical experimentation and for an explosion of subjectivities. He worked on Las Ramblas, in Plaça Reial and Barceloneta, places which began to form a personal map in which he dwelt, and where he started to discover the world after leaving his bourgeois family environment. They were spaces brimming over with life, which were partly founded on flamenco and gypsy culture.

These places gradually shaped a way of looking at reality that was more concerned with relationships and correspondences in space than with the objects and people who occupy it. This can be seen in his "hanging” compositions and his urban landscapes, consisting of figures-masses that recombine and take shape on the canvas, breaking free from perspective, merging architecture and bodies, opening up contours and breaking up figures. During these years Claramunt was influenced by the book Treasure Island, and the characters bloated from drinking alcohol became the bodies that he mixed with while he roamed around the city. Eager to find the extraordinary in the vulgar, making the most of the virtues of anonymity, his walks encapsulate the powers of his imagination and his memory.

In contact with life in all its nakedness, simply witnessing the struggle to survive, with neither compassion nor miserabilism, Claramunt gradually gave shape to his presence in the world and in his painting. Bars, flamenco tablaos, inns and railway stations, gamblers, still lifes, streets and landscapes are the elements that make up the settings and the stories of his work.

2. 1985-1988

The invitation to participate in the exhibition Cota Cero ( ± 0,00) Sobre el nivel del mar was a turning point in his public life and led to his departure from Barcelona. His first stop was Seville, where he found an environment that was favourable to his work, but he also spent periods in Marrakech.

In Seville, a strictly compositional concern prevailed in his work, with almost no colour or texture, at least in the superficial sense of the words. There is no chiaroscuro, except in a very few works, and no real symbolism or description either. Figurative elements are completely subordinated to the resolution of a strictly pictorial space. As for the execution and overall approach, the important thing at this stage was making a mark without any pre-existing plan – brushstrokes without meaning from which he then extracted an idea, a feeling, and linked it to a memory. He basically mixed two realities: the more direct reality of the fortuitous accident, and the less "real" one that can lead to unconscious memory.

The Seville paintings were the limit of an approach based on matter, and a preview to a radical idea that would be expressed in all his later work. The path that leads from the almost monochromatic mark as a space-forming element in the Seville paintings, to the line, the sharp graphism of his late paintings in Morocco and the bulls series, sums up a process that consists of the emptying out of space and the reduction of volume. This progression led to a total predominance of the figure and gesture, in a less naturalistic and more symbolic space, with a tendency towards stylisation that made his painting concise, harder, more cerebral and more concrete.

In his last paintings in Morocco, the bodies are positioned in space, they break up and scatter as superimposed, multiplied silhouettes suggesting rhythmic, disparate motor functions that make reference to different time frames. The enormously disproportionate scale of the figures, their arbitrary nature and the almost complete lack of a setting totally displace the surface of the paintings, contributing to the loss of its ground.

3. 1989-1999

In 1989, Claramunt arrived in Madrid, one of the milestones of his career and the place that led him onto the international scene. In this period he gained brief but intense recognition abroad, particularly in Germany and Austria, with the support of Martin Kippenberger. In the series Shadow Line (1989) he produced totally abstract work, the antithesis of his previous works.

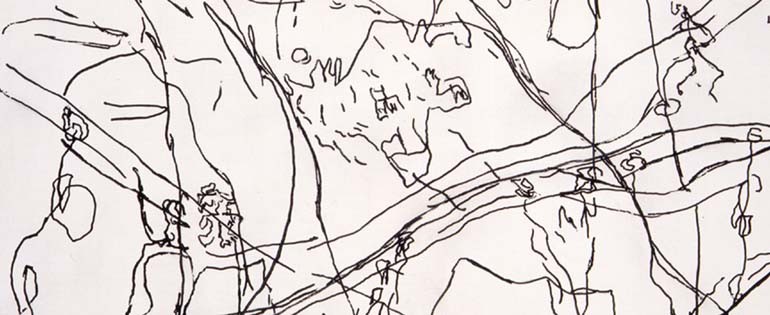

Throughout his career, Claramunt shifted between the figurative and the abstract realms. In the work he produced in this last decade, the abstract marks – which featured in his whole series on seas, shipwrecks and storms – are superimposed with the line, a calligraphic graphism that ended up reduced to black on white in his series on Bilbao and Madrid, with quick brushstrokes that were like scratches on the canvas. Calle Montera in Madrid, and the Bilbao estuary were two of his favourite settings – places of constant flux, dense micro-universes packed with stories of life from which Claramunt gleaned his constant metamorphosis, his agitation and speed, but also his confusion and his suffering.

From 1994 onwards, his output expanded into a compulsive immersion in drawing, photography and book publishing. Claramunt saw drawing as a way of dwelling in and understanding the spaces that he moved through, and the power of his imagination. His drawings distil intense creative energy and translate a working process that arises from strolling and memory, from cities and reading. The drawings acquire significance serially, as though they were a form of writing that could only be perceived through the sequence of the gaze. This walking as artistic practice also determined the form and content of his photographs, in which he simultaneously wrote the text and sought his subjects, taking his photographs “without seeming to”.

Neither his series of drawings nor his photographs extolled their physical or "original" qualities – they were photocopied on paper, sometimes coloured, and bound into books with no exchange value. He printed them himself, prioritising gesture and sequence, the experience of time. In spite of being fragile and quickly made, these publications opened up new opportunities for his work. Along with his drawing series, they focused and liberated a strong poetic tension and summed up his complex past, present and future path.

The Vertical Journey

13 July - 21 October 2012

I don't see any difference between figurative and abstract painting, because painting is, in itself, the image of a reality. A brushstroke can be anything: an insect, a letter, a person. When you create an abstract painting you also start from a particular reality, and then imagination and memory start to work, and that's a reality that is as tangible as any other. Luis Claramunt, El País (5 May, 2000)

The exhibition Luis Claramunt. El viaje vertical features a broad selection of works – including paintings, drawings, photographs and books – produced by the artist from the early seventies to the late nineties. Although Luis Claramunt (Barcelona, 1951 – Zarautz, 2000) is known almost exclusively for his work as a painter, this exhibition presents an entire cosmology that is complex but also unified and consistent, based on his drawing series, his photographic series and his self-published books, which complement and his pictorial work and go beyond it.

Official opening: 12 July 2012. Dates: 13 July – 21 October 2012. Curator: Nuria Enguita Mayo. Organised and produced by: Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA).

1. 1970-1984

Claramunt began his painting career in the late sixties in Barcelona, where he lived on and around Las Ramblas at a time when this iconic promenade was packed with creative potential and had become a stage for radical experimentation and for an explosion of subjectivities. He worked on Las Ramblas, in Plaça Reial and Barceloneta, places which began to form a personal map in which he dwelt, and where he started to discover the world after leaving his bourgeois family environment. They were spaces brimming over with life, which were partly founded on flamenco and gypsy culture.

These places gradually shaped a way of looking at reality that was more concerned with relationships and correspondences in space than with the objects and people who occupy it. This can be seen in his "hanging” compositions and his urban landscapes, consisting of figures-masses that recombine and take shape on the canvas, breaking free from perspective, merging architecture and bodies, opening up contours and breaking up figures. During these years Claramunt was influenced by the book Treasure Island, and the characters bloated from drinking alcohol became the bodies that he mixed with while he roamed around the city. Eager to find the extraordinary in the vulgar, making the most of the virtues of anonymity, his walks encapsulate the powers of his imagination and his memory.

In contact with life in all its nakedness, simply witnessing the struggle to survive, with neither compassion nor miserabilism, Claramunt gradually gave shape to his presence in the world and in his painting. Bars, flamenco tablaos, inns and railway stations, gamblers, still lifes, streets and landscapes are the elements that make up the settings and the stories of his work.

2. 1985-1988

The invitation to participate in the exhibition Cota Cero ( ± 0,00) Sobre el nivel del mar was a turning point in his public life and led to his departure from Barcelona. His first stop was Seville, where he found an environment that was favourable to his work, but he also spent periods in Marrakech.

In Seville, a strictly compositional concern prevailed in his work, with almost no colour or texture, at least in the superficial sense of the words. There is no chiaroscuro, except in a very few works, and no real symbolism or description either. Figurative elements are completely subordinated to the resolution of a strictly pictorial space. As for the execution and overall approach, the important thing at this stage was making a mark without any pre-existing plan – brushstrokes without meaning from which he then extracted an idea, a feeling, and linked it to a memory. He basically mixed two realities: the more direct reality of the fortuitous accident, and the less "real" one that can lead to unconscious memory.

The Seville paintings were the limit of an approach based on matter, and a preview to a radical idea that would be expressed in all his later work. The path that leads from the almost monochromatic mark as a space-forming element in the Seville paintings, to the line, the sharp graphism of his late paintings in Morocco and the bulls series, sums up a process that consists of the emptying out of space and the reduction of volume. This progression led to a total predominance of the figure and gesture, in a less naturalistic and more symbolic space, with a tendency towards stylisation that made his painting concise, harder, more cerebral and more concrete.

In his last paintings in Morocco, the bodies are positioned in space, they break up and scatter as superimposed, multiplied silhouettes suggesting rhythmic, disparate motor functions that make reference to different time frames. The enormously disproportionate scale of the figures, their arbitrary nature and the almost complete lack of a setting totally displace the surface of the paintings, contributing to the loss of its ground.

3. 1989-1999

In 1989, Claramunt arrived in Madrid, one of the milestones of his career and the place that led him onto the international scene. In this period he gained brief but intense recognition abroad, particularly in Germany and Austria, with the support of Martin Kippenberger. In the series Shadow Line (1989) he produced totally abstract work, the antithesis of his previous works.

Throughout his career, Claramunt shifted between the figurative and the abstract realms. In the work he produced in this last decade, the abstract marks – which featured in his whole series on seas, shipwrecks and storms – are superimposed with the line, a calligraphic graphism that ended up reduced to black on white in his series on Bilbao and Madrid, with quick brushstrokes that were like scratches on the canvas. Calle Montera in Madrid, and the Bilbao estuary were two of his favourite settings – places of constant flux, dense micro-universes packed with stories of life from which Claramunt gleaned his constant metamorphosis, his agitation and speed, but also his confusion and his suffering.

From 1994 onwards, his output expanded into a compulsive immersion in drawing, photography and book publishing. Claramunt saw drawing as a way of dwelling in and understanding the spaces that he moved through, and the power of his imagination. His drawings distil intense creative energy and translate a working process that arises from strolling and memory, from cities and reading. The drawings acquire significance serially, as though they were a form of writing that could only be perceived through the sequence of the gaze. This walking as artistic practice also determined the form and content of his photographs, in which he simultaneously wrote the text and sought his subjects, taking his photographs “without seeming to”.

Neither his series of drawings nor his photographs extolled their physical or "original" qualities – they were photocopied on paper, sometimes coloured, and bound into books with no exchange value. He printed them himself, prioritising gesture and sequence, the experience of time. In spite of being fragile and quickly made, these publications opened up new opportunities for his work. Along with his drawing series, they focused and liberated a strong poetic tension and summed up his complex past, present and future path.