Nancy Spero

04 Jul - 24 Sep 2008

NANCY SPERO

"Dissidances"

04/07/2008 - 24/09/2008

Nancy Spero (Cleveland, Ohio, 1926) is one of the pioneers of feminist art and was a key figure on the dissident New York scene of the 1960s and 70s, along with artists like Martha Rosler and Adrian Piper, to whom the MACBA has already devoted individual retrospectives. As an artist and activist, her career is an ongoing example of commitment to the political, social and cultural scene in which we live. A proof of this is her response to the recent warlike events in which her country has become embroiled, events that have resituated her work in the forefront of our times.

Nancy Spero. Dissidances is the first major retrospective of this artist's work to be mounted in both Europe and the United States. The show brings together works that extend from her beginnings as a student at the Art Institute of Chicago, never before exhibited, to her recent presentation at the 2007 Venice Biennale. The title of the exhibition, taken from the text by Hélène Cixous for the catalogue, suggests a potential reading which subsumes two basic aspects of the artist's work: its critical, non-conformist nature in terms of the politico-artistic situation she has lived through during her career and the importance of movement and of the body as vehicles for articulating her discourse. Organized chronologically, the exhibition presents her work as a unitary project in which past and present become blurred, as in the ancient fables and narratives that have been an inspiration to her.

In 1959 Nancy Spero and her husband, Leon Golub, both of them figurative painters established in Chicago, moved with their children to Paris, where they lived from 1959 to 1964, fleeing the preponderance of abstraction on the North-American art scene. In that city Spero made contact with literary, more than artistic, intellectual circles and got deeply involved in readings that would be fundamental, later on, for her work, as in the case of the writings of Artaud. During these early years the artist created a series of works grouped together under the title of Black Paintings (1959-1960). These are figurative pictures of a lyrical expressionism, focusing on themes like night, maternity and lovers, through which characters wander against dark backgrounds laboriously created via the accumulation of layers of paint. The feeling of isolation and impasse that these works transmit correspond to the artist's personal and professional situation at the time.

Spero and Golub returned to New York in 1964, at a moment when opposition to the war in Vietnam and the Civil Rights movement had begun to play a huge role in her country. Her political commitment helped her to escape from her isolation and endowed her with a voice of her own, which would henceforth become the basic research motif in her work. Spero jettisoned painting on canvas, a medium she considered to be male, and settled for the use of paper, whose fragility endowed her painting with a new temporality, procedural quality and expressiveness, as occurs with the series War (1966-1970). In them, Spero gives free rein to her anger and disgust vis-à-vis the war, through manifestos in which she introduces explicit gender imagery and many-layered metaphors about the obscenity and violence of power. Her works are suffused with tongues and phallic bombs, helicopters and defecating mushroom clouds and phrases from military slang. This is an obsessive set of pictures that creates a sort of hieroglyph or visual writing.

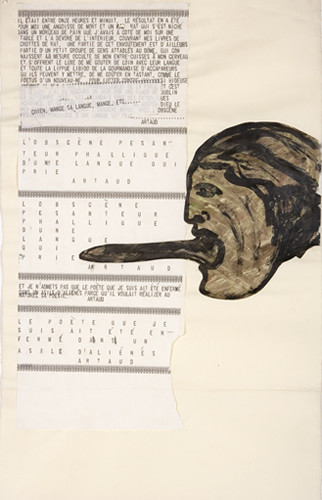

In 1969 Spero distanced herself from the politico-military debate of the time in order to create a group of works based on texts by the French poet Antonin Artaud, the Artaud Paintings (1969-1970). In them she compulsively cites the poet in order to express and exorcise the ire and alienation she was feeling as an artist. These works evolved towards the vast Codex Artaud (1971-1972), consisting of 34 scrolls made up of sheets of paper glued end-to-end. Open-ended in format, this multifarious piece, which recalls ancient writings, marks the mature phase of her work and became a turning point in the art of the 1970s. Unlike that of her conceptualist contemporaries, the language in it is obscene and manually written, like a graffito, giving her work a different sort of corporeality that distances it from the official discourses of the time.

Spero's participation in the feminist movement – she collaborated with WAR (Women Artists in Revolution) and carried out protests and actions to demand an equal amount of representation for men and women in museums – led the artist to deal with issues like women's torture and pain, whilst conveying their strength and freedom. This is the way Torture of Women (1976) came into being, an epic work which combines terrifying images, quotes and testimonies of the atrocities committed by South-American dictatorial regimes against women, according to the reports of Amnesty International and other sources. The piece, a 38-metre-long scroll of fourteen panels, obliges the spectator to traverse the space in a rather unorthodox manner, a formula she would develop in her subsequent works.

The First Language (1981) is her next mega-scroll and marks a point of inflection in her career. With it she abandoned the written word in favor of the female body as a vehicle for expressive language. In this work Spero adopts a deliberately optimistic tone in order to underline the power of the imagination and of hope, in opposition to tyranny and domination. The piece consists of 22 horizontal panels in which female figures proceeding from various historical moments alternate in an extended space, combining presence and emptiness on the blank page. The naked bodies – some of them fragmentary – follow one another and move, leap, fall, stretch, cower and repeat, creating a personal alphabet.

By the end of the 1980s Spero tended more and more towards the hand-printing of figures and backgrounds, and extended her lexicon to include architecture. In this way she did away with any obstacle between the work and the space it was shown in, obliging viewers to participate much more actively by altering their way of looking and their position. In 1998 Spero produced an installation called Let the Priests Tremble... in the Ikon Gallery in London, the central part of which we reproduce in the exhibition. In it, strong, athletic women dance to the sound of a passage from an essay by Hélène Cixous from her book The Laugh of the Medusa. Nancy Spero's rapport with the female writing of authors like Cixous and Kristeva is a recurring theme in critical essays on her work. The artist's interest is also shown in explicit affirmations like, "One cannot advance if it's not in a new direction. The French feminists speak of ‘écriture féminine' and I try to with ‘peinture féminine'." The text by Cixous published in the catalogue to our show presents, like some intimate story, the profound relationship between these two artists.

The 1980s and 90s were years in which she created numerous exhibitions and achieved critical recognition. From then on, Spero's work became more exuberant and affirmative, and expressed – as she put it – a kind of "utopia" involving the possibility of change. Even so, she didn't turn her back on themes and procedures that had interested her since the beginning of her career, like pain, destruction or violence, the both of them becoming two sides of the same coin in terms of her artistic and personal world. The exhibition reflects this duality in two neighboring rooms in which, without following any chronological order, works that establish a dialog between grief and joy are mixed together. Worth highlighting, among these, is Ballad of Marie Sanders, an installation the artist has created in a variety of ways and in which, for the first time in years, she reworks the text with a 1934 Bertolt Brecht poem about a Gentile woman tortured for having had sexual relations with a Jew, as a way of recording the suffering concealed beneath oppressive regimes.

At the end of the 1990s color acquired greater importance in Spero's work, the monumental Azur (2002) being a good example of this. In this piece, which borrows its title from a poem by Mallarmé, the artist deliberately uses color and seeks new and surprising ways of composing a picture, dotting the space with female creatures and creating a dreamlike sequence in which they move without temporal restrictions against a geometrically patterned background. Here, color is handled with the same skill she used to handle text with in the 1970s; by repeating it, combining it, superimposing it, taking liberties with it, leaving it blank, while foregoing the traditional opposition between figure and ground, abstraction and figuration.

Finally, in Maypole: Take No Prisoners (2007), an installation produced for the Venice Biennale, Spero has gone back to a recurrent theme in her work and, alas, in the politics of her country: war. The piece is a maypole with 200 treated and painted aluminum heads that, in the words of the artist, she has cannibalized from her war paintings of the 1960s. With this piece we close the temporal circle of her trajectory; we go back to the beginning and encroach on the chronological boundaries of the retrospective.

Curators:Manuel J. Borja-Villel and Rosario Peiró

Co-produced by: Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS), Madrid

"Dissidances"

04/07/2008 - 24/09/2008

Nancy Spero (Cleveland, Ohio, 1926) is one of the pioneers of feminist art and was a key figure on the dissident New York scene of the 1960s and 70s, along with artists like Martha Rosler and Adrian Piper, to whom the MACBA has already devoted individual retrospectives. As an artist and activist, her career is an ongoing example of commitment to the political, social and cultural scene in which we live. A proof of this is her response to the recent warlike events in which her country has become embroiled, events that have resituated her work in the forefront of our times.

Nancy Spero. Dissidances is the first major retrospective of this artist's work to be mounted in both Europe and the United States. The show brings together works that extend from her beginnings as a student at the Art Institute of Chicago, never before exhibited, to her recent presentation at the 2007 Venice Biennale. The title of the exhibition, taken from the text by Hélène Cixous for the catalogue, suggests a potential reading which subsumes two basic aspects of the artist's work: its critical, non-conformist nature in terms of the politico-artistic situation she has lived through during her career and the importance of movement and of the body as vehicles for articulating her discourse. Organized chronologically, the exhibition presents her work as a unitary project in which past and present become blurred, as in the ancient fables and narratives that have been an inspiration to her.

In 1959 Nancy Spero and her husband, Leon Golub, both of them figurative painters established in Chicago, moved with their children to Paris, where they lived from 1959 to 1964, fleeing the preponderance of abstraction on the North-American art scene. In that city Spero made contact with literary, more than artistic, intellectual circles and got deeply involved in readings that would be fundamental, later on, for her work, as in the case of the writings of Artaud. During these early years the artist created a series of works grouped together under the title of Black Paintings (1959-1960). These are figurative pictures of a lyrical expressionism, focusing on themes like night, maternity and lovers, through which characters wander against dark backgrounds laboriously created via the accumulation of layers of paint. The feeling of isolation and impasse that these works transmit correspond to the artist's personal and professional situation at the time.

Spero and Golub returned to New York in 1964, at a moment when opposition to the war in Vietnam and the Civil Rights movement had begun to play a huge role in her country. Her political commitment helped her to escape from her isolation and endowed her with a voice of her own, which would henceforth become the basic research motif in her work. Spero jettisoned painting on canvas, a medium she considered to be male, and settled for the use of paper, whose fragility endowed her painting with a new temporality, procedural quality and expressiveness, as occurs with the series War (1966-1970). In them, Spero gives free rein to her anger and disgust vis-à-vis the war, through manifestos in which she introduces explicit gender imagery and many-layered metaphors about the obscenity and violence of power. Her works are suffused with tongues and phallic bombs, helicopters and defecating mushroom clouds and phrases from military slang. This is an obsessive set of pictures that creates a sort of hieroglyph or visual writing.

In 1969 Spero distanced herself from the politico-military debate of the time in order to create a group of works based on texts by the French poet Antonin Artaud, the Artaud Paintings (1969-1970). In them she compulsively cites the poet in order to express and exorcise the ire and alienation she was feeling as an artist. These works evolved towards the vast Codex Artaud (1971-1972), consisting of 34 scrolls made up of sheets of paper glued end-to-end. Open-ended in format, this multifarious piece, which recalls ancient writings, marks the mature phase of her work and became a turning point in the art of the 1970s. Unlike that of her conceptualist contemporaries, the language in it is obscene and manually written, like a graffito, giving her work a different sort of corporeality that distances it from the official discourses of the time.

Spero's participation in the feminist movement – she collaborated with WAR (Women Artists in Revolution) and carried out protests and actions to demand an equal amount of representation for men and women in museums – led the artist to deal with issues like women's torture and pain, whilst conveying their strength and freedom. This is the way Torture of Women (1976) came into being, an epic work which combines terrifying images, quotes and testimonies of the atrocities committed by South-American dictatorial regimes against women, according to the reports of Amnesty International and other sources. The piece, a 38-metre-long scroll of fourteen panels, obliges the spectator to traverse the space in a rather unorthodox manner, a formula she would develop in her subsequent works.

The First Language (1981) is her next mega-scroll and marks a point of inflection in her career. With it she abandoned the written word in favor of the female body as a vehicle for expressive language. In this work Spero adopts a deliberately optimistic tone in order to underline the power of the imagination and of hope, in opposition to tyranny and domination. The piece consists of 22 horizontal panels in which female figures proceeding from various historical moments alternate in an extended space, combining presence and emptiness on the blank page. The naked bodies – some of them fragmentary – follow one another and move, leap, fall, stretch, cower and repeat, creating a personal alphabet.

By the end of the 1980s Spero tended more and more towards the hand-printing of figures and backgrounds, and extended her lexicon to include architecture. In this way she did away with any obstacle between the work and the space it was shown in, obliging viewers to participate much more actively by altering their way of looking and their position. In 1998 Spero produced an installation called Let the Priests Tremble... in the Ikon Gallery in London, the central part of which we reproduce in the exhibition. In it, strong, athletic women dance to the sound of a passage from an essay by Hélène Cixous from her book The Laugh of the Medusa. Nancy Spero's rapport with the female writing of authors like Cixous and Kristeva is a recurring theme in critical essays on her work. The artist's interest is also shown in explicit affirmations like, "One cannot advance if it's not in a new direction. The French feminists speak of ‘écriture féminine' and I try to with ‘peinture féminine'." The text by Cixous published in the catalogue to our show presents, like some intimate story, the profound relationship between these two artists.

The 1980s and 90s were years in which she created numerous exhibitions and achieved critical recognition. From then on, Spero's work became more exuberant and affirmative, and expressed – as she put it – a kind of "utopia" involving the possibility of change. Even so, she didn't turn her back on themes and procedures that had interested her since the beginning of her career, like pain, destruction or violence, the both of them becoming two sides of the same coin in terms of her artistic and personal world. The exhibition reflects this duality in two neighboring rooms in which, without following any chronological order, works that establish a dialog between grief and joy are mixed together. Worth highlighting, among these, is Ballad of Marie Sanders, an installation the artist has created in a variety of ways and in which, for the first time in years, she reworks the text with a 1934 Bertolt Brecht poem about a Gentile woman tortured for having had sexual relations with a Jew, as a way of recording the suffering concealed beneath oppressive regimes.

At the end of the 1990s color acquired greater importance in Spero's work, the monumental Azur (2002) being a good example of this. In this piece, which borrows its title from a poem by Mallarmé, the artist deliberately uses color and seeks new and surprising ways of composing a picture, dotting the space with female creatures and creating a dreamlike sequence in which they move without temporal restrictions against a geometrically patterned background. Here, color is handled with the same skill she used to handle text with in the 1970s; by repeating it, combining it, superimposing it, taking liberties with it, leaving it blank, while foregoing the traditional opposition between figure and ground, abstraction and figuration.

Finally, in Maypole: Take No Prisoners (2007), an installation produced for the Venice Biennale, Spero has gone back to a recurrent theme in her work and, alas, in the politics of her country: war. The piece is a maypole with 200 treated and painted aluminum heads that, in the words of the artist, she has cannibalized from her war paintings of the 1960s. With this piece we close the temporal circle of her trajectory; we go back to the beginning and encroach on the chronological boundaries of the retrospective.

Curators:Manuel J. Borja-Villel and Rosario Peiró

Co-produced by: Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS), Madrid