Alex Hanimann

06 Jun - 16 Sep 2012

The Eternal Detour cycle, summer sequence 2012

ALEX HANIMANN

No proof, no commentary, no double entendre

6 June - 16 September 2012

French-speaking visitors to Mamco are bound to be surprised by the title of Alex Hanimann’s exhibition, for the expression ‘double entendre’, although well established in English, does not exist in French. The same bizarrerie can be found throughout the exhibition. Word play is a key feature of Hanimann’s work, whose other main component, the world of images, has been displayed here at Mamco on several occasions.

The artist’s approach is part of a set of highly varied contemporary practices at the interface between art and words, which began developing in all directions at the start of the twentieth century. Written language has since become an increasingly prominent feature of the visual arts, and the specifically visual nature of writing has sometimes even resulted in the elimination of all other elements. This is the point of contact between the two facets of Alex Hanimann’s work, which subtly meet in some of his drawings, with the text hovering above the pictorial matter like a heading or contained in an expressive comic-strip balloon.

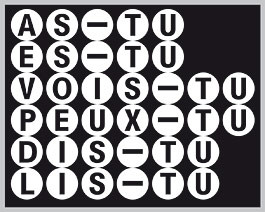

When he gets away from images and works with ‘pure’ language, Hanimann exploits all its resources: punctuation marks, words, sentences, phonetics and switching from one language to another. In response to Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913), who said that ‘the graphic sign is an image or form worthy of consideration in and for itself’, Hanimann offers us all the different uses that he instils into the typographic material. His pages of text, as small as a book or as large as a wall, are not as varied as the bits of newspaper found in Cubist works, but they are firmly grounded in the field of writing. Letters and figures acquire visual properties as much through their drawn or typewritten form as through their arrangement on the page. As we know, Stéphane Mallarmé (1842-1898) was the first to break free from the traditional constraints of printing, but it is surprising to learn that text was invented later than writing. History relates that the first superintendent of the Library of Alexandria, Zenodotus of Ephesus (third century BCE), when confronted with the many problems of reading and filing written matter (particularly scriptio continua), introduced the first means of organising it visually on the page, namely blank spaces between words1.

Alex Hanimann’s work seeks to move beyond purely graphic research, which is not so much a goal as a starting point, a release mechanism for the viewer’s ideas, a linguistic trigger. The artist juggles with words, alert to their meanings and those that may emerge when they are juxtaposed, assembled, underlined, crossed out, read backwards or translated into another language.

‘To arrange is to interpret’ is one of Hanimann’s favourite sayings. Observing and analysing his extensive output — his picture drawings and his work with language — as well as his impressive archive of photographs cut from newspapers and magazines dealing with society and politics, he has felt a pressing need to create his own thesaurus, even at the risk of getting lost in it. This has resulted in thematic corpora. Given the artist’s encyclopaedic interest in language, his thematic arrangement is based on ways of use, rules of all kinds, puns, logic, everyday language, lists of words, axioms, and the rhythms and sounds of words. By the same token, his images are arranged into groups made up of plants, animals, abstract drawings, dancing, characters that act, characters that present themselves, and so on.

Whether painted on walls, blown into neon tubes, drawn in gouache letter by letter and assembled in monumental collages or shaped like illuminated signs, Alex Hanimann’s texts, even if they suggest possible linkages of meaning, somehow remain ‘floating’. This is because they never impose an exact or absolute meaning — instead, readers are free to grasp their meaning and make their own associations as they read them.

1. Nina Catach, ‘Retour aux sources’, Traverses, No. 43, February 1988, pp. 33-47.

Alex Hanimann was born in Mörschwil, Switzerland, in 1955, and now lives in St Gallen.

* This English translation has been provided with the support of the J.P. Morgan Private Bank.

ALEX HANIMANN

No proof, no commentary, no double entendre

6 June - 16 September 2012

French-speaking visitors to Mamco are bound to be surprised by the title of Alex Hanimann’s exhibition, for the expression ‘double entendre’, although well established in English, does not exist in French. The same bizarrerie can be found throughout the exhibition. Word play is a key feature of Hanimann’s work, whose other main component, the world of images, has been displayed here at Mamco on several occasions.

The artist’s approach is part of a set of highly varied contemporary practices at the interface between art and words, which began developing in all directions at the start of the twentieth century. Written language has since become an increasingly prominent feature of the visual arts, and the specifically visual nature of writing has sometimes even resulted in the elimination of all other elements. This is the point of contact between the two facets of Alex Hanimann’s work, which subtly meet in some of his drawings, with the text hovering above the pictorial matter like a heading or contained in an expressive comic-strip balloon.

When he gets away from images and works with ‘pure’ language, Hanimann exploits all its resources: punctuation marks, words, sentences, phonetics and switching from one language to another. In response to Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913), who said that ‘the graphic sign is an image or form worthy of consideration in and for itself’, Hanimann offers us all the different uses that he instils into the typographic material. His pages of text, as small as a book or as large as a wall, are not as varied as the bits of newspaper found in Cubist works, but they are firmly grounded in the field of writing. Letters and figures acquire visual properties as much through their drawn or typewritten form as through their arrangement on the page. As we know, Stéphane Mallarmé (1842-1898) was the first to break free from the traditional constraints of printing, but it is surprising to learn that text was invented later than writing. History relates that the first superintendent of the Library of Alexandria, Zenodotus of Ephesus (third century BCE), when confronted with the many problems of reading and filing written matter (particularly scriptio continua), introduced the first means of organising it visually on the page, namely blank spaces between words1.

Alex Hanimann’s work seeks to move beyond purely graphic research, which is not so much a goal as a starting point, a release mechanism for the viewer’s ideas, a linguistic trigger. The artist juggles with words, alert to their meanings and those that may emerge when they are juxtaposed, assembled, underlined, crossed out, read backwards or translated into another language.

‘To arrange is to interpret’ is one of Hanimann’s favourite sayings. Observing and analysing his extensive output — his picture drawings and his work with language — as well as his impressive archive of photographs cut from newspapers and magazines dealing with society and politics, he has felt a pressing need to create his own thesaurus, even at the risk of getting lost in it. This has resulted in thematic corpora. Given the artist’s encyclopaedic interest in language, his thematic arrangement is based on ways of use, rules of all kinds, puns, logic, everyday language, lists of words, axioms, and the rhythms and sounds of words. By the same token, his images are arranged into groups made up of plants, animals, abstract drawings, dancing, characters that act, characters that present themselves, and so on.

Whether painted on walls, blown into neon tubes, drawn in gouache letter by letter and assembled in monumental collages or shaped like illuminated signs, Alex Hanimann’s texts, even if they suggest possible linkages of meaning, somehow remain ‘floating’. This is because they never impose an exact or absolute meaning — instead, readers are free to grasp their meaning and make their own associations as they read them.

1. Nina Catach, ‘Retour aux sources’, Traverses, No. 43, February 1988, pp. 33-47.

Alex Hanimann was born in Mörschwil, Switzerland, in 1955, and now lives in St Gallen.

* This English translation has been provided with the support of the J.P. Morgan Private Bank.