Luc Andrié

05 Jun - 15 Sep 2013

LUC ANDRIÉ

Bolaño

5 June - 15 September 2013

Ten years after his exhibition Rien d’aimable (’Nothing nice’), and five years after presenting his strange portraits of the painter in his underpants (which he refuses to call self-portraits) at the Printemps de Toulouse, Luc Andrié is back at Mamco with a series of nineteen paintings entitled Bolaño. There is no longer anything uncomfortable about his subjects, his virtuosity is now accepted—and yet there is a problem. In the words of a famous art historian, ’There’s nothing there.’

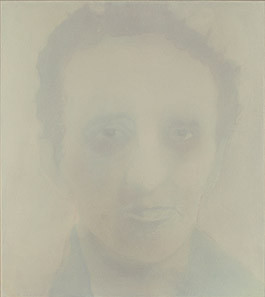

The previous exhibition in the Cabinet des abstraits presented the photographic work of Pierre-Olivier Arnaud, in which the image had so little contrast that it seemed about to vanish into indeterminate greyness. In this sense, Luc Andrié provides a kind of continuity with his pale rectangles in unrewarding tones—grey-green with the odd hint of pink. The persevering viewer sees a face gradually emerging, but you have to look at it for a long time to make out a gaze that becomes a face, a closed face—and eventually realise that it is always the same one.

The face belongs to the Chilean poet and novelist Roberto Bolaño, who died ten years ago. Andrié became his travelling companion—an imaginary conversation partner. Moved by Bolaño’s sober yet shocking texts that tell without pathos of uprootedness, human misery and the depth of feeling—in short, the difficulty of being a poet—he wanted to prolong his encounter with the author. The nineteen paintings thus relate this silent consultation between painter and writer, the artist’s approach to this now mythical island in the archipelago of literature, in a Borgesian light. Each painting embolies the reading of the nineteen books by Bolaño that have been translated into French, from which each title selects a word that links the painter to the author.

But Andrié is not content just to pay tribute. His work as a painter also involves tackling the difficulties of his medium. What is the place—not to say legitimacy—of painted portraits in this day and age? How can you express what photography cannot, and how can you tackle the legacy of the portrait’s history? Such questions would suffice to wipe out the image, and hence—metaphorically speaking—they filter or obstruct its perception. And yet the face remains, like the painting. ’Disappearance isn’t my thing,’ says Andrié, ’it’s too romantic for me.’ This seems a paradoxical statement, given the care the painter takes to let the face emerge only in small stages, as though it had to pass through the hundred or so layers that lend his paintings pictorial depth. Yet he sees the persistence of the real and the face despite the filters—the screens that hide the picture or, in Bolaño’s writing, the violence that obliterates poetic activity.

The portraits of Bolaño are all derived from a single image found on the Internet. Painting from photography is a practice as old as Niépce and Daguerre’s invention itself, for painters have always considered that they can capture on the canvas something of the ’domain of the impalpable and the imaginary’ upon which photography should not be allowed to ’encroach’ (Baudelaire, The Salon of 1859). In Luc Andrié’s work, the shift from photographic to painted image adds an important time dimension. The instantaneous snapshot is drawn out into a laborious process of successive coatings, in which tones are nuanced through transparency. The result is a painted image, one that is very hard to photograph and is only very gradually revealed to our eyes. Thus, in contrast to the immediacy of the photograph—from snapshot to viewing—the experience of painting is closer to that of literature, in which our gaze advances and progresses step by step, entering a world in which what we see must be enhanced by what we imagine.

Luc Andrié was born in Pretoria in 1954 and now lives in La Russille, a hamlet in the Swiss canton of Vaud.

Bolaño

5 June - 15 September 2013

Ten years after his exhibition Rien d’aimable (’Nothing nice’), and five years after presenting his strange portraits of the painter in his underpants (which he refuses to call self-portraits) at the Printemps de Toulouse, Luc Andrié is back at Mamco with a series of nineteen paintings entitled Bolaño. There is no longer anything uncomfortable about his subjects, his virtuosity is now accepted—and yet there is a problem. In the words of a famous art historian, ’There’s nothing there.’

The previous exhibition in the Cabinet des abstraits presented the photographic work of Pierre-Olivier Arnaud, in which the image had so little contrast that it seemed about to vanish into indeterminate greyness. In this sense, Luc Andrié provides a kind of continuity with his pale rectangles in unrewarding tones—grey-green with the odd hint of pink. The persevering viewer sees a face gradually emerging, but you have to look at it for a long time to make out a gaze that becomes a face, a closed face—and eventually realise that it is always the same one.

The face belongs to the Chilean poet and novelist Roberto Bolaño, who died ten years ago. Andrié became his travelling companion—an imaginary conversation partner. Moved by Bolaño’s sober yet shocking texts that tell without pathos of uprootedness, human misery and the depth of feeling—in short, the difficulty of being a poet—he wanted to prolong his encounter with the author. The nineteen paintings thus relate this silent consultation between painter and writer, the artist’s approach to this now mythical island in the archipelago of literature, in a Borgesian light. Each painting embolies the reading of the nineteen books by Bolaño that have been translated into French, from which each title selects a word that links the painter to the author.

But Andrié is not content just to pay tribute. His work as a painter also involves tackling the difficulties of his medium. What is the place—not to say legitimacy—of painted portraits in this day and age? How can you express what photography cannot, and how can you tackle the legacy of the portrait’s history? Such questions would suffice to wipe out the image, and hence—metaphorically speaking—they filter or obstruct its perception. And yet the face remains, like the painting. ’Disappearance isn’t my thing,’ says Andrié, ’it’s too romantic for me.’ This seems a paradoxical statement, given the care the painter takes to let the face emerge only in small stages, as though it had to pass through the hundred or so layers that lend his paintings pictorial depth. Yet he sees the persistence of the real and the face despite the filters—the screens that hide the picture or, in Bolaño’s writing, the violence that obliterates poetic activity.

The portraits of Bolaño are all derived from a single image found on the Internet. Painting from photography is a practice as old as Niépce and Daguerre’s invention itself, for painters have always considered that they can capture on the canvas something of the ’domain of the impalpable and the imaginary’ upon which photography should not be allowed to ’encroach’ (Baudelaire, The Salon of 1859). In Luc Andrié’s work, the shift from photographic to painted image adds an important time dimension. The instantaneous snapshot is drawn out into a laborious process of successive coatings, in which tones are nuanced through transparency. The result is a painted image, one that is very hard to photograph and is only very gradually revealed to our eyes. Thus, in contrast to the immediacy of the photograph—from snapshot to viewing—the experience of painting is closer to that of literature, in which our gaze advances and progresses step by step, entering a world in which what we see must be enhanced by what we imagine.

Luc Andrié was born in Pretoria in 1954 and now lives in La Russille, a hamlet in the Swiss canton of Vaud.