Robert Heinecken

05 Jun - 15 Sep 2013

ROBERT HEINECKEN

Le Paraphotographe

5 June - 15 September 2013

How do you present a photographic work amid a profusion of images? What resources do you use? And what are you trying to say? These are questions Robert Heinecken began asking himself in the early 1960s. As an artist he set out to explore these issues over the next four decades, and as a professor at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA) he awoke generations of students to their existence. Yet, ironically, his position in the field of photography relegated him to the sidelines of institutional fame and commercial success, even though the worthwhile answers he sought early on made him highly influential among artists themselves.

Even today, in an age of Babel-like image banks, there is something exhilarating about the work of an artist who blended his vocabularies, for instance by corrupting documentary photography with images from advertising or pornography. But the humour and charm, however wry, that recur throughout his work should not blind us to his serious approach to theoretical issues (especially on the use of the photographic medium) and social ones alike. Heinecken used the term ’paraphotographer’ to describe his ambiguous relationship with his medium. On the one hand, he almost always used existing images that he compiled or arranged to create his own works, which might lead some to consider that he was not a photographer in the strict sense of the term; yet he was a true virtuoso in printing and trans- fer techniques, understanding their connotations and using the various methods as styles in their own right.

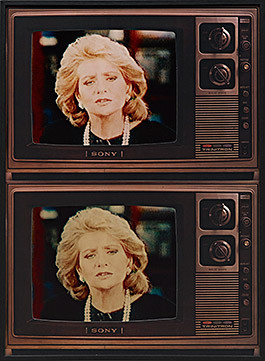

In an age of widespread protest, Robert Heinecken used guerrilla techniques to disseminate his work, altering magazines which were then redistributed in kiosks or salons. The subversive ability of these altered magazines was enhanced by the surprise effect. On 28 November 1969, the cover of Time Magazine showed a strange photograph of an epoxy-resin portrait of Raquel Welch, by the sculp- tor Frank Gallo. Heinecken enhanced the ambiguity by overprinting on the inner pages erotic photographs that distorted the meaning of the articles and focused on the depiction of women as mere objects. Far more scathing and merciless was Related to periodical #5, in which a picture of a smiling woman soldier brandishing two severed heads was superimposed on advertisements for anti-baldness creams, or on an article about birth control from women’s point of view. Heinecken worked in series. For instance, the various Lessons in Posing Subjects brought together pictures rephotographed as Polaroids and arranged according to posture. He used ironic captions to mock the standardising impact of the mass media, especially television, which he saw as a place of involuntary surrealism. Several of his series dealt with this issue, mixing up presenters’ faces or highlighting the absurdity of the televised spectacle.

’I make something to see what it looks like,’ said Heinecken, ’and to see if it looks like anything else.’ Given the diversity of the methods he tried out, and the issues he tackled, his work was unlike any other—diagnosing the ills of the society he was part of, and tracing the history of artistic research in the closing decades of the twentieth century.

Robert Heinecken was born in Denver, Colorado, in 1931 and died in 2006 in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Le Paraphotographe

5 June - 15 September 2013

How do you present a photographic work amid a profusion of images? What resources do you use? And what are you trying to say? These are questions Robert Heinecken began asking himself in the early 1960s. As an artist he set out to explore these issues over the next four decades, and as a professor at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA) he awoke generations of students to their existence. Yet, ironically, his position in the field of photography relegated him to the sidelines of institutional fame and commercial success, even though the worthwhile answers he sought early on made him highly influential among artists themselves.

Even today, in an age of Babel-like image banks, there is something exhilarating about the work of an artist who blended his vocabularies, for instance by corrupting documentary photography with images from advertising or pornography. But the humour and charm, however wry, that recur throughout his work should not blind us to his serious approach to theoretical issues (especially on the use of the photographic medium) and social ones alike. Heinecken used the term ’paraphotographer’ to describe his ambiguous relationship with his medium. On the one hand, he almost always used existing images that he compiled or arranged to create his own works, which might lead some to consider that he was not a photographer in the strict sense of the term; yet he was a true virtuoso in printing and trans- fer techniques, understanding their connotations and using the various methods as styles in their own right.

In an age of widespread protest, Robert Heinecken used guerrilla techniques to disseminate his work, altering magazines which were then redistributed in kiosks or salons. The subversive ability of these altered magazines was enhanced by the surprise effect. On 28 November 1969, the cover of Time Magazine showed a strange photograph of an epoxy-resin portrait of Raquel Welch, by the sculp- tor Frank Gallo. Heinecken enhanced the ambiguity by overprinting on the inner pages erotic photographs that distorted the meaning of the articles and focused on the depiction of women as mere objects. Far more scathing and merciless was Related to periodical #5, in which a picture of a smiling woman soldier brandishing two severed heads was superimposed on advertisements for anti-baldness creams, or on an article about birth control from women’s point of view. Heinecken worked in series. For instance, the various Lessons in Posing Subjects brought together pictures rephotographed as Polaroids and arranged according to posture. He used ironic captions to mock the standardising impact of the mass media, especially television, which he saw as a place of involuntary surrealism. Several of his series dealt with this issue, mixing up presenters’ faces or highlighting the absurdity of the televised spectacle.

’I make something to see what it looks like,’ said Heinecken, ’and to see if it looks like anything else.’ Given the diversity of the methods he tried out, and the issues he tackled, his work was unlike any other—diagnosing the ills of the society he was part of, and tracing the history of artistic research in the closing decades of the twentieth century.

Robert Heinecken was born in Denver, Colorado, in 1931 and died in 2006 in Albuquerque, New Mexico.