Július Koller

Subjektobjekt

17 Jan - 24 Feb 2018

JÚLIUS KOLLER

Subjektobjekt

17 January – 24 February 2018

In 1969, artist Július Koller inscribed a question mark onto the surface of a tennis court. Within the context of the artist’s practice, the semantics of the gesture were not so usual. After all, in its serpentine course, the punctuation mark had the power to throw an entire statement into flux. This made it the ideal icon for the ambiguity and uncertainty of the times, following the Prague Spring and the ensuing Soviet invasion, which had promptly wiped the “human face” off Czechoslovakia’s bespoke brand of socialism. But the question mark also had an elasticity that could stretch beyond the localized and apply to the universal. For this reason, Koller had taken up the cipher as his signature motif, branding the symbol on banners, ping-pong paddles and even the façades of old wooden houses.

But this wasn’t just any old wall; this was a field of play. An athlete himself, Koller knew well that tennis is a sport predicated on demarcation; the placement of a line on the court determines whether or not a ball is fair play. By altering the markings on the ground, the artist did not see himself as vandalizing the court; rather, he was proposing a new set of conditions for the game.

Curator Vít Havránek has suggested that, for Koller, the appeal of sports lies precisely in the fact that – at a moment when the protocols governing society had seemingly peeled away – games still remained bound by rules. Yet Koller had a complicated relationship to rules. He certainly didn’t play by those set by the traditional art academy, where he trained formally, but he also demonstrated little interest in following the well-hobbled path of the dissident or unofficial artist. In this sense, he eluded the art historical clichés around Eastern European Conceptualism as an archipelago of one-man-islands of isolated genius, toiling against a society that cruelly misunderstood them. Koller aimed to throw these very taxonomies into flux, thereby unsettling the hierarchies that would cordon off “artistic genius” as a province of the intellectual elite. This is not to say that Koller did not meticulously consider each gesture, weighing his terminology carefully and issuing definitions or manifestos as needed. But a personal point of pride for him was his decades-long engagement teaching amateur artists (even though he himself eschewed the theatrics of plein air easel painting in favor of copying from cheap tourist postcards).

Similarly, Koller’s trumpeting of the prefix “anti-” – at play in his “Anti-Pictures” or “Anti-Happenings”– signaled a rejection of the more rarefied forms of contemporary art. This rejection was amplified by his pointed use of humble materials, such as white latex paint, cast-off clothing or ping-pong paddles. In his practice, however, the artist still replicated some of techniques of auto-canonization, drawing up rigorous critical chronologies of his own work. Anti-establishment in spirit, his “Anti-Happenings” were nevertheless dutifully recorded and documented, with official announcements issued via text cards. Granted, these announcements rarely contained more than the artist’s name or initials, the year, and perhaps the title of the series or maybe just “Anti-Happening”.

With each of these gestures, Koller set up an act of opposition, not as a block, but as a return volley – an invitation to respond in kind. The artist understood his work as not merely reacting against the limitations of his political and social situation, but instead actively striving to produce new “cultural situations” altogether, using a bit of dialectic reasoning. As the artist described it on one of his undated manuscript cards: “My game never ends; it is played out continually in an undefined rhythm and intensity”. The point wasn’t to win; it was to constantly push the game forward through a negotiation of infinitely renewed oppositions, keeping the ball in motion.

Koller once described his use of the question mark to his fellow artist Roman Ondak as “both leaving a trail and sending out a signal”. Another source of transmissions could be found in his long-running project, Universal-Cultural Futurological Operations (1970–2007), or “U.F.O.”. Like the question mark, these three initials remained in constant flux, allowing the artist to shuffle or substitute potential assignations for each letter. For instance, “U” stood for “Universal-Cultural”, a nod to Koller’s theories of Cosmohumanist Culture, but “U” could also mean “Utopian” or “Undisclosed”. In the same way, “F” morphed from “Futurological” to “Philosophical”, “Folkloristic”, or even “Fantastic”. As the object, the “O” was perhaps the most flexible of the letters, denoting “Organization”, “Ornament”, “Object”, “Obraz” (“Image”) or, crucially, “Otáznik” (“Question Mark”). In his 1970 manifesto for U.F.O., Koller explained that establishing such a mutable field of play enabled him to move beyond just producing a new set of aesthetic objects, to instead engender “a new life, a new subject, awareness, creativity, and a new cultural reality”.

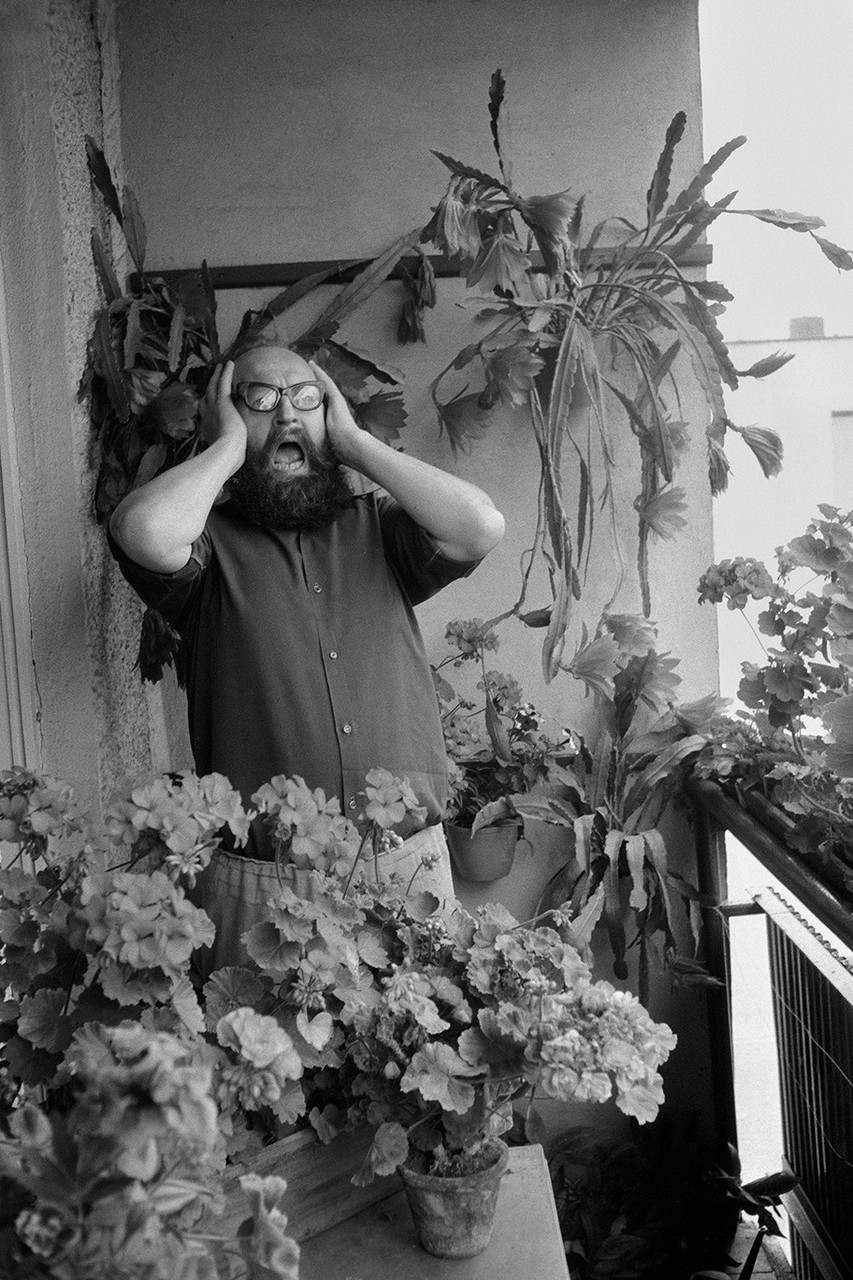

This new life demanded new life forms. Starting in 1970, Koller embarked on a series of annual portraits of himself as a “U.F.O.-naut”. Each fresh image incorporated props that might have been symbolic for the artist in that particular moment – be it fishing nets, pretzels, a Tate gift bag or the two tennis balls tucked behind his glasses for the inaugural photoshoot. (The last image later reappeared as the backdrop for the 1990 piece, Slovenský Trans-Art). In each of these portraits, Koller embraced the humor and absurdity of his chosen prop, but he left few clues for the casual observer to decipher any deeper meaning. Therein lies the nature of Koller’s game. His objective was not to fix things with a definite end, but rather to stand in as the question mark that keeps it all in motion.

Kate Sutton

Subjektobjekt

17 January – 24 February 2018

In 1969, artist Július Koller inscribed a question mark onto the surface of a tennis court. Within the context of the artist’s practice, the semantics of the gesture were not so usual. After all, in its serpentine course, the punctuation mark had the power to throw an entire statement into flux. This made it the ideal icon for the ambiguity and uncertainty of the times, following the Prague Spring and the ensuing Soviet invasion, which had promptly wiped the “human face” off Czechoslovakia’s bespoke brand of socialism. But the question mark also had an elasticity that could stretch beyond the localized and apply to the universal. For this reason, Koller had taken up the cipher as his signature motif, branding the symbol on banners, ping-pong paddles and even the façades of old wooden houses.

But this wasn’t just any old wall; this was a field of play. An athlete himself, Koller knew well that tennis is a sport predicated on demarcation; the placement of a line on the court determines whether or not a ball is fair play. By altering the markings on the ground, the artist did not see himself as vandalizing the court; rather, he was proposing a new set of conditions for the game.

Curator Vít Havránek has suggested that, for Koller, the appeal of sports lies precisely in the fact that – at a moment when the protocols governing society had seemingly peeled away – games still remained bound by rules. Yet Koller had a complicated relationship to rules. He certainly didn’t play by those set by the traditional art academy, where he trained formally, but he also demonstrated little interest in following the well-hobbled path of the dissident or unofficial artist. In this sense, he eluded the art historical clichés around Eastern European Conceptualism as an archipelago of one-man-islands of isolated genius, toiling against a society that cruelly misunderstood them. Koller aimed to throw these very taxonomies into flux, thereby unsettling the hierarchies that would cordon off “artistic genius” as a province of the intellectual elite. This is not to say that Koller did not meticulously consider each gesture, weighing his terminology carefully and issuing definitions or manifestos as needed. But a personal point of pride for him was his decades-long engagement teaching amateur artists (even though he himself eschewed the theatrics of plein air easel painting in favor of copying from cheap tourist postcards).

Similarly, Koller’s trumpeting of the prefix “anti-” – at play in his “Anti-Pictures” or “Anti-Happenings”– signaled a rejection of the more rarefied forms of contemporary art. This rejection was amplified by his pointed use of humble materials, such as white latex paint, cast-off clothing or ping-pong paddles. In his practice, however, the artist still replicated some of techniques of auto-canonization, drawing up rigorous critical chronologies of his own work. Anti-establishment in spirit, his “Anti-Happenings” were nevertheless dutifully recorded and documented, with official announcements issued via text cards. Granted, these announcements rarely contained more than the artist’s name or initials, the year, and perhaps the title of the series or maybe just “Anti-Happening”.

With each of these gestures, Koller set up an act of opposition, not as a block, but as a return volley – an invitation to respond in kind. The artist understood his work as not merely reacting against the limitations of his political and social situation, but instead actively striving to produce new “cultural situations” altogether, using a bit of dialectic reasoning. As the artist described it on one of his undated manuscript cards: “My game never ends; it is played out continually in an undefined rhythm and intensity”. The point wasn’t to win; it was to constantly push the game forward through a negotiation of infinitely renewed oppositions, keeping the ball in motion.

Koller once described his use of the question mark to his fellow artist Roman Ondak as “both leaving a trail and sending out a signal”. Another source of transmissions could be found in his long-running project, Universal-Cultural Futurological Operations (1970–2007), or “U.F.O.”. Like the question mark, these three initials remained in constant flux, allowing the artist to shuffle or substitute potential assignations for each letter. For instance, “U” stood for “Universal-Cultural”, a nod to Koller’s theories of Cosmohumanist Culture, but “U” could also mean “Utopian” or “Undisclosed”. In the same way, “F” morphed from “Futurological” to “Philosophical”, “Folkloristic”, or even “Fantastic”. As the object, the “O” was perhaps the most flexible of the letters, denoting “Organization”, “Ornament”, “Object”, “Obraz” (“Image”) or, crucially, “Otáznik” (“Question Mark”). In his 1970 manifesto for U.F.O., Koller explained that establishing such a mutable field of play enabled him to move beyond just producing a new set of aesthetic objects, to instead engender “a new life, a new subject, awareness, creativity, and a new cultural reality”.

This new life demanded new life forms. Starting in 1970, Koller embarked on a series of annual portraits of himself as a “U.F.O.-naut”. Each fresh image incorporated props that might have been symbolic for the artist in that particular moment – be it fishing nets, pretzels, a Tate gift bag or the two tennis balls tucked behind his glasses for the inaugural photoshoot. (The last image later reappeared as the backdrop for the 1990 piece, Slovenský Trans-Art). In each of these portraits, Koller embraced the humor and absurdity of his chosen prop, but he left few clues for the casual observer to decipher any deeper meaning. Therein lies the nature of Koller’s game. His objective was not to fix things with a definite end, but rather to stand in as the question mark that keeps it all in motion.

Kate Sutton