Gabriel Vormstein

25 Jan - 08 Mar 2014

GABRIEL VORMSTEIN

Papyrus containing the spell to preserve it ́s possessor II

25 January - 8 March 2014

Shadows of Young Girls in Flower

Who wants yesterday`s papers?

Who wants yesterday`s girl? –Mick Jagger

Subterranean substrate and the pull underground. The bed of these new compositions is a mulch of shredded newspaper and magazines, periodicals way past their period, composting in a field of temporal pulp. And what do we find in this soiled bed? Young girls contorted against a dirty backdrop, painted long ago, yet forever made new by generations of teenage eyes, discovering their sick bodies, realizing that sex, influenza, and art all have something in common.

You love her for how new she is, and because she’ll let you see things earlier paintings would not. Her manner is equally frank and timid;, vulnerable, protected by history, but at the same time, present. But heres the familiar story: you leave her behind when you go to university. She is from your earlier stages. She is from a moment when art was romantic, and when you didnt need to be embarrassed by that. But that moment has evaporated. You move on.

In Gabriel Vormsteins work, images of flowers, bodies, and geometric blocks float atop a surface thinly draped with paint. All take place on fragile, provisional alternatives to canvas. He uses newspaper, realizing that as it ages, it will yellow to the color of a smokers teeth

and fingertips. It isnt archival; it is cirrhotic. The newspaper is constantly both new and out of date. It testifies, to paraphrase Sontag, to times relentless crumble. In recent works, the substrate moves from sheets of newsprint to a mixture of different publications that Vormstein first made by hand and then with the help of a commercial shredder. To add a biological feel to the mixture, he collaged in bits of wood, plastic bags, food, and dried flowers, creating a landfill that is still somehow fertile. It has shredded art history—the still life, the memento mori, the landscape are all reduced to their physical material.

It’s initially surprising that such a versatile artist has taken the Egon Schiele girl as his signature. After all, she is one of the great symbols of Modernist reification of style. The doyenne of sexually charged high school art classes, she signaled something alive. Of course, when you looked at her more closely, she looked quite dead.

Like the models he painted, the Viennese painters life and art are caught in the middle of youth and death, eros and thanatos; of pre-modern and modern eras, and of freedom and institutionalization. It is the force of those many binaries pushing against the figures that causes the strong line work for which Schiele is rightfully known. Here Vormstein blurs it a bit, but it remains an instantly recognizable outline.

The figures have been painted in a diffuse miasma of color reminiscent of some internal hemorrhage. Schieles figures, with their malnourished dis- and double-jointed limbs, pert nipples, and heavy genitals, have long been symbols of decadence and disease. They are sexually inclined, although not inclined to the type of sex you might want to have. Vormsteins seem to be an internal reading of that same unwellness. Imagine tuberculosis

bacterium spreading through a segment of lung tissue. Imagine blood through mucus. Thats how his pigments move through those empty forms. They are agents of infection, mute germs. You catch them as a teenager in love, awash in agape, but then you’re embarrassed

in the morning.

What are the girls up against? Bless their arrhythmic hearts, theyre up against the world. Within the cosmology of Vormsteins painting, theyre up against the brutal contemporaneity of the newsprint substrate. As hallucinations from another century, they emerge from the present day. And thats just the dateline. They must also struggle against the headlines, those noting the crisis of financial and political order, and the advertisements. These young girls differ from Tiqquns Young Girl. They come before I shop, therefore I am. Their existence, then and now, is simultaneous youth and death. But here, placed atop a bed of lingerie ads, they cannot help but illustrate our age. They are both consumptive and consumer.

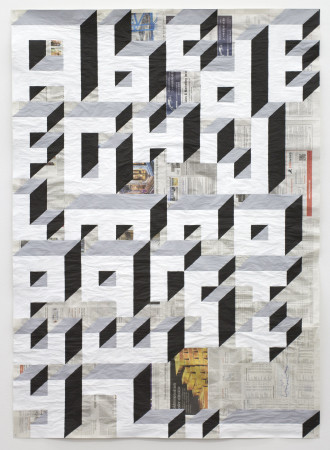

Then, there are the geometric blocks that hold the bodies in check. These paintings, also done on newsprint, mock the monumentality of minimalism. They are playful games created out of those architectural bunkers, be they of concrete or ideology, which surround us. Put another way, the minimalist tendencies evinced in the blocks couldn’t be further away from that painterly variety of expressionistic turmoil. When added to the figures and the pulp, these blocks complete the cycle that moves from destruction to construction, and from romantic feeling to analytic thought.

Past the limits of the paintings, the girls must hold their own in a disapproving world. It is not so much that they are prostitutes, but that they are Schieles. And Schiele, well, didnt you grow out of him? Hes like Plath, important in youth, but then left behind.

That is why Vormsteins appropriation of the images is so brilliant. Its not simply mining modernism, but mining ones own development, falling back on oneself, proposing different paths through art and life. Here, the use of Schiele is a detour around the roadblocks of todays painting, good or bad. Because why does badness have to be a formal game? Why cant it be closer to bad taste, or to bad conduct? These paintings are fever dreams of

appropriation. Not of that smug Pictures Generation hermetics, but of an elevated form of teenage cribbing. They get at that moment of release that always exists before embarrassment. And if most of todays painting is anything, it is embarrassed, fragile, and sick of itself.

When looking at a reprieve from a death of painting, it makes sense to reexamine earlier periods, to sift through the stockroom, as it were, looking for something that could make sense again. This retrospection is tiring, however, and it is easily exhausted. There is only so

much that came before. Another way to reinvigorate history, to shake the corpse, is to return to earlier moments in your life as an artist, as a viewer. We all grow up. Relationships that made sense in high school sometimes no longer work, but sometimes they do. Return from the university to those dirty rooms of youth. Someone might still be there.

Hunter Braithwaite

Papyrus containing the spell to preserve it ́s possessor II

25 January - 8 March 2014

Shadows of Young Girls in Flower

Who wants yesterday`s papers?

Who wants yesterday`s girl? –Mick Jagger

Subterranean substrate and the pull underground. The bed of these new compositions is a mulch of shredded newspaper and magazines, periodicals way past their period, composting in a field of temporal pulp. And what do we find in this soiled bed? Young girls contorted against a dirty backdrop, painted long ago, yet forever made new by generations of teenage eyes, discovering their sick bodies, realizing that sex, influenza, and art all have something in common.

You love her for how new she is, and because she’ll let you see things earlier paintings would not. Her manner is equally frank and timid;, vulnerable, protected by history, but at the same time, present. But heres the familiar story: you leave her behind when you go to university. She is from your earlier stages. She is from a moment when art was romantic, and when you didnt need to be embarrassed by that. But that moment has evaporated. You move on.

In Gabriel Vormsteins work, images of flowers, bodies, and geometric blocks float atop a surface thinly draped with paint. All take place on fragile, provisional alternatives to canvas. He uses newspaper, realizing that as it ages, it will yellow to the color of a smokers teeth

and fingertips. It isnt archival; it is cirrhotic. The newspaper is constantly both new and out of date. It testifies, to paraphrase Sontag, to times relentless crumble. In recent works, the substrate moves from sheets of newsprint to a mixture of different publications that Vormstein first made by hand and then with the help of a commercial shredder. To add a biological feel to the mixture, he collaged in bits of wood, plastic bags, food, and dried flowers, creating a landfill that is still somehow fertile. It has shredded art history—the still life, the memento mori, the landscape are all reduced to their physical material.

It’s initially surprising that such a versatile artist has taken the Egon Schiele girl as his signature. After all, she is one of the great symbols of Modernist reification of style. The doyenne of sexually charged high school art classes, she signaled something alive. Of course, when you looked at her more closely, she looked quite dead.

Like the models he painted, the Viennese painters life and art are caught in the middle of youth and death, eros and thanatos; of pre-modern and modern eras, and of freedom and institutionalization. It is the force of those many binaries pushing against the figures that causes the strong line work for which Schiele is rightfully known. Here Vormstein blurs it a bit, but it remains an instantly recognizable outline.

The figures have been painted in a diffuse miasma of color reminiscent of some internal hemorrhage. Schieles figures, with their malnourished dis- and double-jointed limbs, pert nipples, and heavy genitals, have long been symbols of decadence and disease. They are sexually inclined, although not inclined to the type of sex you might want to have. Vormsteins seem to be an internal reading of that same unwellness. Imagine tuberculosis

bacterium spreading through a segment of lung tissue. Imagine blood through mucus. Thats how his pigments move through those empty forms. They are agents of infection, mute germs. You catch them as a teenager in love, awash in agape, but then you’re embarrassed

in the morning.

What are the girls up against? Bless their arrhythmic hearts, theyre up against the world. Within the cosmology of Vormsteins painting, theyre up against the brutal contemporaneity of the newsprint substrate. As hallucinations from another century, they emerge from the present day. And thats just the dateline. They must also struggle against the headlines, those noting the crisis of financial and political order, and the advertisements. These young girls differ from Tiqquns Young Girl. They come before I shop, therefore I am. Their existence, then and now, is simultaneous youth and death. But here, placed atop a bed of lingerie ads, they cannot help but illustrate our age. They are both consumptive and consumer.

Then, there are the geometric blocks that hold the bodies in check. These paintings, also done on newsprint, mock the monumentality of minimalism. They are playful games created out of those architectural bunkers, be they of concrete or ideology, which surround us. Put another way, the minimalist tendencies evinced in the blocks couldn’t be further away from that painterly variety of expressionistic turmoil. When added to the figures and the pulp, these blocks complete the cycle that moves from destruction to construction, and from romantic feeling to analytic thought.

Past the limits of the paintings, the girls must hold their own in a disapproving world. It is not so much that they are prostitutes, but that they are Schieles. And Schiele, well, didnt you grow out of him? Hes like Plath, important in youth, but then left behind.

That is why Vormsteins appropriation of the images is so brilliant. Its not simply mining modernism, but mining ones own development, falling back on oneself, proposing different paths through art and life. Here, the use of Schiele is a detour around the roadblocks of todays painting, good or bad. Because why does badness have to be a formal game? Why cant it be closer to bad taste, or to bad conduct? These paintings are fever dreams of

appropriation. Not of that smug Pictures Generation hermetics, but of an elevated form of teenage cribbing. They get at that moment of release that always exists before embarrassment. And if most of todays painting is anything, it is embarrassed, fragile, and sick of itself.

When looking at a reprieve from a death of painting, it makes sense to reexamine earlier periods, to sift through the stockroom, as it were, looking for something that could make sense again. This retrospection is tiring, however, and it is easily exhausted. There is only so

much that came before. Another way to reinvigorate history, to shake the corpse, is to return to earlier moments in your life as an artist, as a viewer. We all grow up. Relationships that made sense in high school sometimes no longer work, but sometimes they do. Return from the university to those dirty rooms of youth. Someone might still be there.

Hunter Braithwaite