Melvin Moti

10 Sep - 22 Oct 2011

Melvin Moti

Eigengrau (The Inner Self In Outer Space)

09.09.2011 - 22.10.2011

"We are not a social history museum!”

We are pleased to present the first exhibition in our gallery by Dutch artist Melvin Moti (Rotterdam, 1977). The exhibition consists of a new 35mm film installation, a series of photographs and a limited-edition artist book.

The Victoria and Albert Museum started as a collection devoted to design classics from around the world. It was primarily developed after The Great Exhibition, which took place in the Crystal Palace in London in 1851. The Great Exhibition, much like the Victoria and Albert Museum remains today, was a showcase of material grandeur. It was organized and installed out of an encyclopaedic desire to chart global developments in industrial design and handcrafts, while simultaneously setting up a primary index of taste. A more straightforward, capitalist objective was to seduce future consumers to invest in British industrial design by introducing a broad audience to refined objects. When the exhibition came to its end, Henry Cole, who was in charge of the Great Exhibition, received a grant from the British government to purchase a number of design objects that had been on display in the Crystal Palace. These pieces were the first in the collection of what would become the Victoria and Albert Museum. Today, the museum holds a wide range of work from all corners of the world, related to contemporary art and culture as well as advertising and popular culture (the collection of contemporary Indian film posters for example).

Over the course of a century, the Victoria and Albert Museum has developed a number of provocative positions that have been criticised frequently.. Time and again, the Museum focuses on revealing the "inherent qualities" of its exhibited items. By giving a minimal amount of contextual information, the objects are left to communicate by and for themselves. Here, artworks are completely objectified, posing questions in terms of their own inner structure and logic. Devoid of any sense of historic framework, the inherent trait of a certain technique or material lends the object its intrinsic value—an into-the-body-experience of an object.

At the same time, this approach makes it terribly difficult for any visitor to fully grasp the museum’s exhibits. The lack of contextual information, along with the sheer magnitude of the collection, makes the Victoria and Albert Museum the only institution that actually discourages visitors from engaging with its collection. From the early years of the museum until today, the museum has simply been too cluttered, too full, too visually over-stimulating, since a new image is registered at each glance, leaving the visitor’s mind wholly saturated at first sight. The antihistorical and anti-social museological dogma of the Victoria and Albert Museum lead to the statement that this is "not a social history museum” and in the past the museum has described itself as a "glorified warehouse”. The formal categorization based on the material of objects turns the aesthetic eye of the beholder into a "geological” gaze, interested exclusively in surfaces, materials and techniques. In effect, this minimalized contextual information turns the museum’s exhibits into free-floating, disconnected objects. In absence of extensive informational and educational resources for their exhibitions; in absence of a conventional vestibular vocabulary, this collection starts to float. Detached from imposed narratives, objects begin to drift away from any understanding through a historic, chronological or social framework. Chaos ensues. Confusion follows. Coming to termswith this place is as difficult as pissing into a cup in outer space; this is a zero gravity museum.

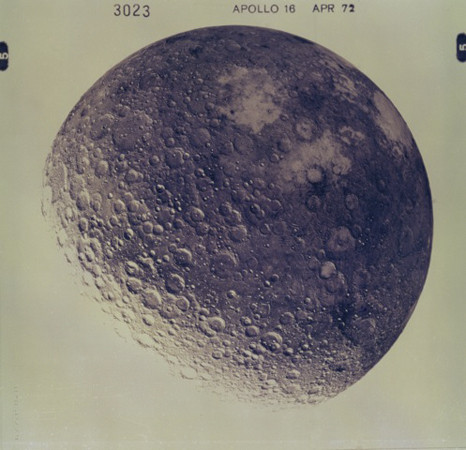

Eigengrau (The Inner Self in Outer Space) is a zero-gravity exhibition in film format, combining the hyper-materialistic antique objects from the V&A collection with the tactility of celestial bodies from our solar system, travelling from the inner construction of each object (glass, wood, gold, etc.) into outer space. The film shows painted moons and decorative pieces moving along various orbits, captured in slow-paced images, and propels these man-made objects into an atmosphereof detachment and suspension, in seemingly weightless disconnection from all points of reference.

Eigengrau completely foregoes digital technology and emphasises the hand-crafted skills in the large-scale science-fiction productions of the 1970s. The film is accompanied by a series of photographs which portray the collection pieces (the cast) featured in the film. An artist book presenting an essay is a key part of this project, written by the artist, it investigates several conceptual threads relating to the inherent qualities of language and objects. The artist book is not instructive or documentary, it is not a catalogue so to speak, but an autonomous element of the project.

Moti examines neurological, scientific and historic processes in relation to visual culture. Over the last years he produced several films along with artist books, objects and drawings. Moti has had solo exhibitions at Mudam (Luxembourg), MIT List Visual Arts Center (Boston), Wiels (Brussels), Galeria Civica (Trento), MMK (Frankfurt), Frac Champagne-Ardenne (Reims) and Stedelijk ́Museum (Amsterdam).

Eigengrau (The Inner Self In Outer Space)

09.09.2011 - 22.10.2011

"We are not a social history museum!”

We are pleased to present the first exhibition in our gallery by Dutch artist Melvin Moti (Rotterdam, 1977). The exhibition consists of a new 35mm film installation, a series of photographs and a limited-edition artist book.

The Victoria and Albert Museum started as a collection devoted to design classics from around the world. It was primarily developed after The Great Exhibition, which took place in the Crystal Palace in London in 1851. The Great Exhibition, much like the Victoria and Albert Museum remains today, was a showcase of material grandeur. It was organized and installed out of an encyclopaedic desire to chart global developments in industrial design and handcrafts, while simultaneously setting up a primary index of taste. A more straightforward, capitalist objective was to seduce future consumers to invest in British industrial design by introducing a broad audience to refined objects. When the exhibition came to its end, Henry Cole, who was in charge of the Great Exhibition, received a grant from the British government to purchase a number of design objects that had been on display in the Crystal Palace. These pieces were the first in the collection of what would become the Victoria and Albert Museum. Today, the museum holds a wide range of work from all corners of the world, related to contemporary art and culture as well as advertising and popular culture (the collection of contemporary Indian film posters for example).

Over the course of a century, the Victoria and Albert Museum has developed a number of provocative positions that have been criticised frequently.. Time and again, the Museum focuses on revealing the "inherent qualities" of its exhibited items. By giving a minimal amount of contextual information, the objects are left to communicate by and for themselves. Here, artworks are completely objectified, posing questions in terms of their own inner structure and logic. Devoid of any sense of historic framework, the inherent trait of a certain technique or material lends the object its intrinsic value—an into-the-body-experience of an object.

At the same time, this approach makes it terribly difficult for any visitor to fully grasp the museum’s exhibits. The lack of contextual information, along with the sheer magnitude of the collection, makes the Victoria and Albert Museum the only institution that actually discourages visitors from engaging with its collection. From the early years of the museum until today, the museum has simply been too cluttered, too full, too visually over-stimulating, since a new image is registered at each glance, leaving the visitor’s mind wholly saturated at first sight. The antihistorical and anti-social museological dogma of the Victoria and Albert Museum lead to the statement that this is "not a social history museum” and in the past the museum has described itself as a "glorified warehouse”. The formal categorization based on the material of objects turns the aesthetic eye of the beholder into a "geological” gaze, interested exclusively in surfaces, materials and techniques. In effect, this minimalized contextual information turns the museum’s exhibits into free-floating, disconnected objects. In absence of extensive informational and educational resources for their exhibitions; in absence of a conventional vestibular vocabulary, this collection starts to float. Detached from imposed narratives, objects begin to drift away from any understanding through a historic, chronological or social framework. Chaos ensues. Confusion follows. Coming to termswith this place is as difficult as pissing into a cup in outer space; this is a zero gravity museum.

Eigengrau (The Inner Self in Outer Space) is a zero-gravity exhibition in film format, combining the hyper-materialistic antique objects from the V&A collection with the tactility of celestial bodies from our solar system, travelling from the inner construction of each object (glass, wood, gold, etc.) into outer space. The film shows painted moons and decorative pieces moving along various orbits, captured in slow-paced images, and propels these man-made objects into an atmosphereof detachment and suspension, in seemingly weightless disconnection from all points of reference.

Eigengrau completely foregoes digital technology and emphasises the hand-crafted skills in the large-scale science-fiction productions of the 1970s. The film is accompanied by a series of photographs which portray the collection pieces (the cast) featured in the film. An artist book presenting an essay is a key part of this project, written by the artist, it investigates several conceptual threads relating to the inherent qualities of language and objects. The artist book is not instructive or documentary, it is not a catalogue so to speak, but an autonomous element of the project.

Moti examines neurological, scientific and historic processes in relation to visual culture. Over the last years he produced several films along with artist books, objects and drawings. Moti has had solo exhibitions at Mudam (Luxembourg), MIT List Visual Arts Center (Boston), Wiels (Brussels), Galeria Civica (Trento), MMK (Frankfurt), Frac Champagne-Ardenne (Reims) and Stedelijk ́Museum (Amsterdam).