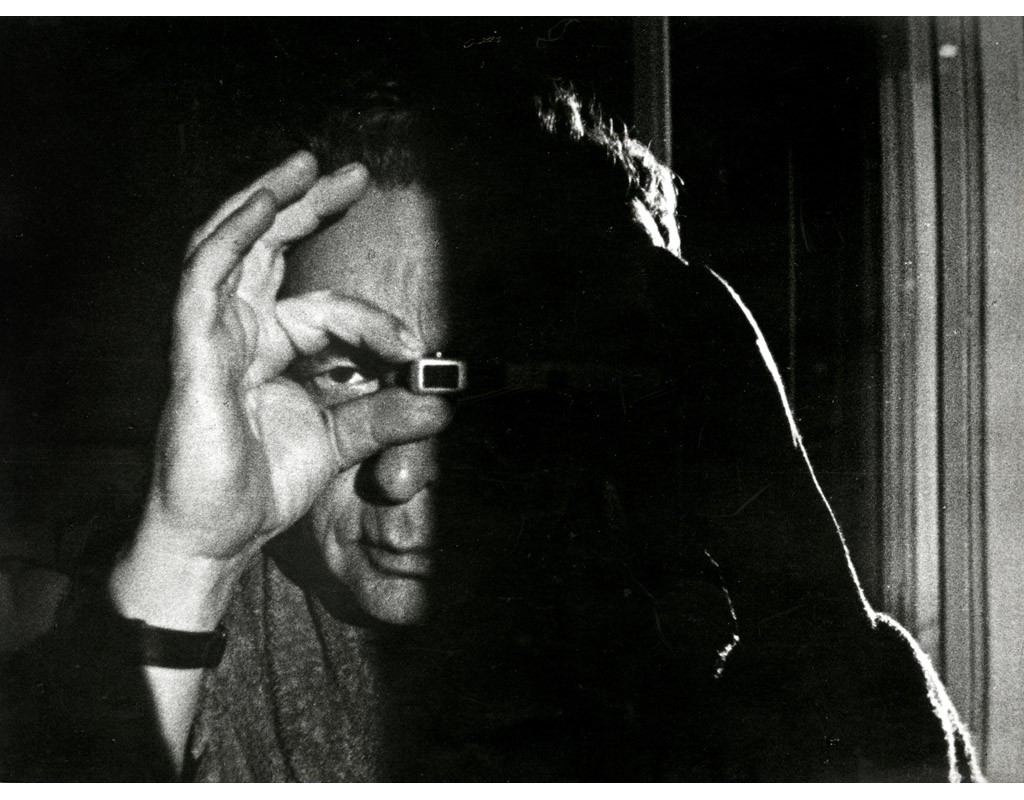

Hans Hartung

And Photography

05 Jun - 09 Sep 2016

“I took photos of everything that interested me in the world: people, clouds, water, mountains, cracks, stains, and all sorts of light and shade effects, which – sometimes – have a more or less direct relationship to my painting.”

There are approximately 30,000 photographic negatives in the estate of Hans Hartung (1904-1989) – an unbelievable number, only part of which the artist had developed.

Hartung, who was undeniably one of the most significant representatives of 20th-century abstract painting, organized the prints in numerous albums, arranged both chronologically and thematically. Besides series of portraits and landscapes, there are also many abstract photos or experiments with light and shade.

In Hartung's case this fascination with photography began in his childhood. Later, during his artistic training and in the subsequent years of intense debate with painting, Hartung continued to experiment with the medium. In 1932 he began to work directly with the negatives, which he scratched, exposed and painted on. At that time, cameras were incapable of providing the kind of spontaneous shot we are familiar with today. This changed with the development of the pocket camera, which Hartung used intensively; often equipped with two different devices (a Minox and a Leica), he took the aforementioned portrait series, landscape shots and abstract photos in this way.

In painting, Hartung was always reinventing himself. From 1972 onwards, in his studio in Antibes, his productivity increased particularly: helped by up to six assistants, Hartung painted up to a dozen pictures each day. Using a still more radical process in his final years of life, despite partial paralysis and life in a wheelchair, he produced paintings in less than a minute – a parallel to the speed of the photographic method. This exciting relationship between the media photography and painting is illuminated in an exemplary way in the exhibition by means of comparison with works from the collection Lambrecht-Schadeberg/Rubens Prize-winners of the City of Siegen stored in the museum. As a result, the production and creativity of the first Rubens Prize-winner of the City of Siegen in 1958 can be perceived in a fresh way.

Hartung's photos themselves, which have never been shown publicly in this form before, will be at the forefront of the presentation in Siegen. But Hans Hartung's photographic practice will also be examined. Besides the question of the material's arrangement, the exhibition in the Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen pursues questions concerning the relation of image and series, abstraction and figuration, and also examines image creation using a wide range of devices.

There are approximately 30,000 photographic negatives in the estate of Hans Hartung (1904-1989) – an unbelievable number, only part of which the artist had developed.

Hartung, who was undeniably one of the most significant representatives of 20th-century abstract painting, organized the prints in numerous albums, arranged both chronologically and thematically. Besides series of portraits and landscapes, there are also many abstract photos or experiments with light and shade.

In Hartung's case this fascination with photography began in his childhood. Later, during his artistic training and in the subsequent years of intense debate with painting, Hartung continued to experiment with the medium. In 1932 he began to work directly with the negatives, which he scratched, exposed and painted on. At that time, cameras were incapable of providing the kind of spontaneous shot we are familiar with today. This changed with the development of the pocket camera, which Hartung used intensively; often equipped with two different devices (a Minox and a Leica), he took the aforementioned portrait series, landscape shots and abstract photos in this way.

In painting, Hartung was always reinventing himself. From 1972 onwards, in his studio in Antibes, his productivity increased particularly: helped by up to six assistants, Hartung painted up to a dozen pictures each day. Using a still more radical process in his final years of life, despite partial paralysis and life in a wheelchair, he produced paintings in less than a minute – a parallel to the speed of the photographic method. This exciting relationship between the media photography and painting is illuminated in an exemplary way in the exhibition by means of comparison with works from the collection Lambrecht-Schadeberg/Rubens Prize-winners of the City of Siegen stored in the museum. As a result, the production and creativity of the first Rubens Prize-winner of the City of Siegen in 1958 can be perceived in a fresh way.

Hartung's photos themselves, which have never been shown publicly in this form before, will be at the forefront of the presentation in Siegen. But Hans Hartung's photographic practice will also be examined. Besides the question of the material's arrangement, the exhibition in the Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen pursues questions concerning the relation of image and series, abstraction and figuration, and also examines image creation using a wide range of devices.