In Place Of

10 Jan - 19 Feb 2016

Sarah Charlesworth, Liz Deschenes, Liz Glynn, Rochelle Goldberg, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Nicolàs

Guagnini & Gareth James, Pierre Huyghe, Silvia Kolbowski, Louise Lawler & Allan McCollum, Dana

Lok, Lee Lozano, Jean-Luc Moulène, Julia Phillips, Karin Schneider, Lawrence Weiner, Eric Vysocan

10 January – 19 February 2016

Curated by Leah Pires

“So, where are you? You are in a space that is designed to make any object in the space more visible.”1

But what about that which is absent? In a space where visibility is currency, how can withdrawal—resistance to representation—become legible?

Most often it can’t. (It’s said that Lee Lozano disappeared without a trace around the time of her Dropout Piece, c. 1970-72, but in fact she remained in New York making undocumented work—with actions, walks, words—for another decade. You won’t find any of it here, though).

But when withdrawal does become palpable, it’s through a placeholder: an object that occupies space in order to gesture toward a lack, an absent agent, or something that has been barred from representation. (Gayatri Spivak observes that representation itself isalways a ‘standing-for’ or a ‘speaking-for.’ Gilles Deleuze describes it as a lining or hem, stretched around the borders of the thing it seeks to represent.) The objects in this space stand in for things that are not in this space. They are a form of ‘making do,’ but not an end in themselves.

“What does it mean to be invited?”2

In 1979, a group of female filmmakers were invited to contribute to the exhibition Film as Film:Formal Experiment in Film 1910- 1975. In the end, they choseto leave their allotted room empty except for a printed statement—“the only form of intervention open to us”—condemning the exhibition committee’s refusal to acknowledge the political (feminist, anti-war, and labor rights) activities of the filmmakers whose work would have been featured.3

According to Alberti’s 15th -century treatise on painting, “only that which occupies its place is a representable object.”4 Which raises the question: what does it mean to have a place?

“[A]n object alone is more visible than an object in a group.” 5

This exhibition brings together works that, in various ways, might be understood as placeholders: for objects withdrawn for legal or political reasons; for absent bodies; for anticipated content; for unfilled desires or needs; for the otherwise forgotten; for those who chose to drop out; or simply because a surrogate was good enough.

An exhibition spaceis, after all, characterized by the presence of certain things and the willful suppression of others. Where better to examine our own investments?

Sarah Charlesworth’s Fear of Nothing, a late addition to her Objects of Desire series, turns on a double entendre. A ‘horror vacui mask’ (the artist’s term for her appropriated cutout) trains its sight on a reflective void. What is ‘nothing’? “Fear of death, fear of the unknown, fear of not having the next artwork, or the fear of castration, of the unarticulated,” she said.

Liz Deschenes materializes a component of the photographic and cinematic apparatus whose ideal is disappearance. Her Green Screens bring a special effects tool whose form is entirely dictated by function (i.e. maximal replaceablity) into the space of exhibition, where abstraction too often functions as the consummate placeholder.

Liz Glynn casts in lead surrogates of quotidian objects smuggled by tunnel from Egypt into the Gaza Strip (as reported in journalistic accounts since 2007). They are remarkable for their utter banality: garlic, cigarettes, potato chips, perfume.

Rochelle Goldberg tests our psychological attachment to barriers. “The blank is an assertion of empty space. It is expectant,” she writes. “The blank is something we fill, and in filling it, it fills us, A repository for our stare, we blank at it and it blanks back. It echoes our three-dimensionality back to a two-dimensional space that can push all forwards, flat, and back.”

Felix Gonzalez-Torrescharts the steady decline of a patient’s T-cells, marking lowered immunity in graphite and gouache.

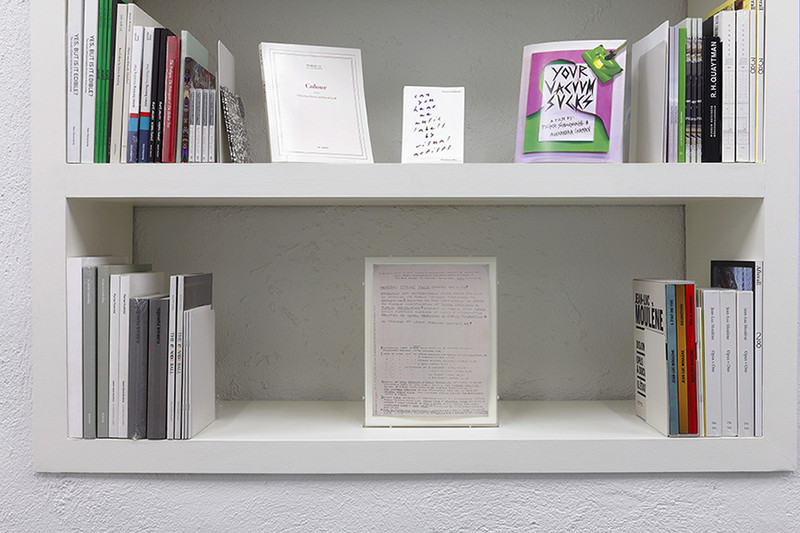

Nicolàs Guagnini & Gareth James advertised their 2006 exhibition Break Even with a blank page in Artforum. (The magazine prohibited an entirely baresheet, so the artistsadded a thin frameto define its perimeter.) Hereit multiples in space, implicating the gallery walls as pages in its sheaf. Are we still breaking even?

Pierre Huyghe captures Lucie Dolène, the French actress who lent her voice to the French version of Walt Disney’s Snow White, against the blue cyclorama of a film production studio.“Today when I watch the film I have a strange feeling, it’s my voice and yet it doesn’t seem to belong to me anymore,” the subtitles relate while Dolène sings ‘Someday My Prince Will Come.’

Silvia Kolbowski probes the gap between eventand memory by collecting retrospective accounts of ‘dematerialized’ artworks from twenty-two of the period’s protagonists. Here, thesplit between sound and image is only one of many.

Louise Lawler & Allan McCollum’s Fixed Intervals—ornamental forms borrowed from typesetting—are used to take the place of other artworks. At the gallery’s Orchard Street location, their configuration mimes that of the precedingexhibition, yet its sculpturesand drawingsare conspicuously absent. A second order of displacement is catalyzed by pending economic transactions: artworks that are sold from the installation at 88 Eldridge will swap locations with a brass object from 36 Orchard.

Dana Lok punctures the conventions of pictorial representation (in two and three dimensions) with the slipperiness of indexical speech. Which side are you on?

Lee Lozano’s tool drawings—preliminary sketches for large-scale paintings in oil on canvas—suggest erotic contact between surrogate forms, while her subsequent Masturbation Investigation trades in one kind of tool for another.

Jean-Luc Moulène seeks to produce “work that is, in itself, the site of conflict.”In the case of his photographic inventory of Objets de Grève (‘Strike Objects’), this aim is doubled by his subject matter: an array of modified products made by French laborers during work stoppages between the 1970s and 1990s.

Julia Phillipssutures ceramic body casts onto welded steel to create seemingly utilitarian forms that invite contact of an ambiguous kind. Desire and control are held in tension, unresolved.

Karin Schneider occupies the square, here staging a phantasmagoric dialogue with Ad Reinhardt by signing his silence. “In order for any work to be visible, it has to be absorbed by those who authorize it,” she has written elsewhere.

Lawrence Weiner’s 36" x 36" removal to the lathing or support wall of plaster or wallboard from a wallmarks the site of a ‘blind window’—a sealed window bayconcealed behind plywood on the building’s interior, yet betrayed by a concrete silhouette on its exterior. Our superficial excavation leaves the cavity intact.

Eric Wysocan’s self-redacting sculpture, fueled by a coal miner’s headlamp, accumulatesagainst its own visibility. Nearby, alloy coins cast from a Greek drachme marked with the stamp of Diogenes counterfeit an ancient counterfeit. Money as the universal equivalent: “The Point Is to (Ex)change It.”

1 Christopher D’Arcangelo, “Four Texts, for Artists Space,” exhibited in , Louise Lawler, Adrian Piper and Cindy Sherman are participating in an exhibition organized by Janelle Reiring at Artists Space, September 23 to October 28, 1978. Box 1, Folder 4, Series 1, Christopher D’Arcangelo Papers, Fales Library and Special Collections, NYU.

2 Christopher D’Arcangelo, “Look Out for What You Look At,” 19 June 1978. Box 2, Folder 1, Series 1, Christopher D’Arcangelo Papers. Statement written in response to a retracted invitation to participate in a group exhibition at Rosa Esman Gallery in June 1978.

3 Annabel Nicolson, Felicity Sparrow, Jane Clarke, Jeannette Iljon, Lis Rhodes, Mary Pat Leece, Pat Murphy, Susan Stein, “Woman and the Formal Film.” Film as Film: Formal Experiment in Film 1910-1975. Exh. cat. London: Hayward Gallery South Bank, 1979. The authors of the statement had intended to use the space to present the work of Maya Deren, Germaine Dulac, and Alice Guy.

4 Bernard Siegert, “(Not) in Place: The Grid, or, Cultural Techniques of Ruling Spaces,” in Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real, translated by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young (New York: Fordham University Press, 2015), 100.

5 D’Arcangelo, “Four Texts, for Artists Space.”