James Benning & Peter Hutton

24 Jan - 08 Mar 2015

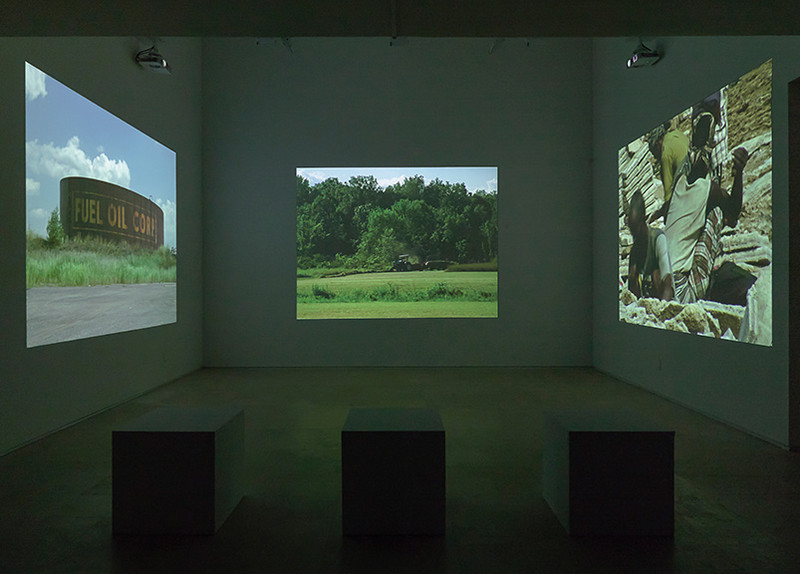

James Benning & Peter Hutton

Nature is a Discipline

Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, 2015

Installation view

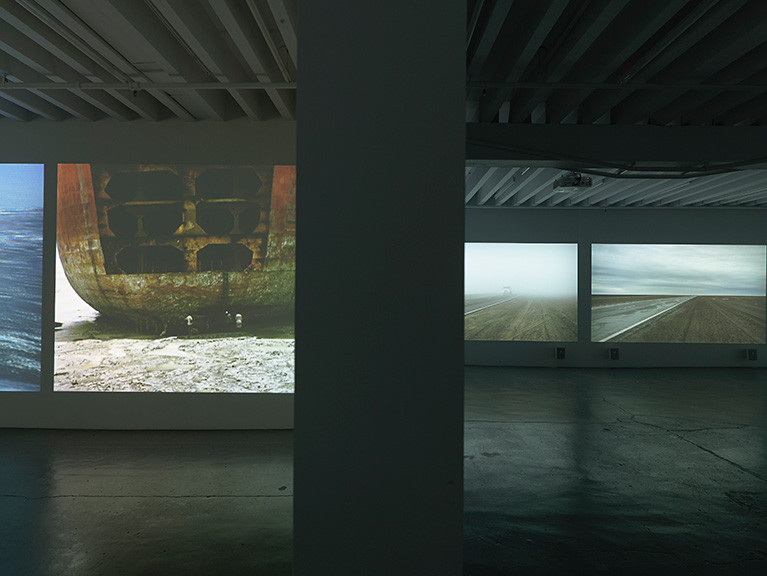

Nature is a Discipline

Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, 2015

Installation view

JAMES BENNING & PETER HUTTON

Nature is a Discipline

24 January – 8 March 2015

Curated by Ed Halter

Miguel Abreu Gallery is pleased to announce the opening, on Saturday, January 24, of Nature is a Discipline, an exhibition of film and video works by James Benning and Peter Hutton at both gallery locations.

Internationally recognized as two of the most accomplished American filmmakers of their generation, Benning and Hutton have been making motion pictures since the early 1970s; up until just the past few years, both have primarily worked in 16mm. The two men have related interests in documenting our modern relationship to landscapes, both natural and manmade, but do so with distinct approaches and sensibilities that have evolved over the decades. Recently, they have each responded to the increased difficulties of working in small-gauge celluloid by turning to new technologies. Since 2009, Benning has abandoned film to create new moving-image work exclusively using video, ranging from high-definition cinematography to appropriated YouTube clips, while Hutton has begun transferring work produced on 16mm to digital formats for screening.

As a result of this shift to digital, both artists have begun making pieces intended for installation in galleries and museum spaces, in addition to new works for theatrical projection in cinemas. Nature is a Discipline presents three recent installations that will show for the first time in New York: Hutton’s At Sea(2004-07) and Three Landscapes (2013), and Benning's Tulare Road(2010).

At Seais a new iteration of Hutton's longform 16mm work of the same name, transformed into three looping channels that echo the tripartite structure of the earlier film. Hutton, himself a former seaman with the Merchant Marines, documents the life of a modern cargo ship through each of these sections, from a ship’s construction in a South Korean port, to frosty journeys across the northern Atlantic, to workers disassembling a rusting ship for scrap on the shores of the Indian Ocean. Three Landscapes is also composed of three parts, but here the sections play off one another in ways more comparative than narrative. Each channel examines groups of laborers in vastly different locales: salt miners in the deserts of Ethiopia, farm workers in the green Hudson Valley, and bridge repairmen in post-industrial Detroit. As with Hutton’s 16mm films, both At Seaand Three Landscapesare projected silently, allowing for a deeper engagement with their remarkable sense of composition and elegantly unhurried pace.

Benning shot Tulare Road on a highway in California's Central Valley, an area that the director had previously explored in his film El Valley Centro (2000). Here, the only part of the SoCal landscape pictured is a lonely stretch of road extending to a distant horizon. Shot three times and presented on three adjoining channels, each version displays an almost identical composition of land and road under different weather formations, from dense fog to cloudy blue skies. The startling clarity of HD video plays against the landscape’s eerie stillness, broken intermittently by the rising and falling roar of passing cars or trucks. While Benning has always gravitated towards a kind of minimalism in his filmmaking, his work in the last decade has, at times, become ever more formally attenuated, and Tulare Roadcontinues his interest in the extended long take framed by a fixed camera, here enhanced by the repetition of the multiple channels and their infinite looping. “I have an interest in exploring space-time relationships through film,” Benning has stated. “There’s real time, and there’s how we perceive time.

Time affects the way we perceive place. That’s where I get this idea of ‘looking and listening.’ In my films, I’m very aware of recording place over time, and the way that makes you understand place. Once you’ve been watching something for a while, you become aware of it differently.”[1]

Writing on At Sea's theatrical version for Artforum, P. Adams Sitney argued that Hutton’s work is exemplary of the longstanding influence of Emersonian ideas on the American avant-garde cinema, particularly Emerson’s belief that we can teach ourselves to experience the world, through looking, in ways that can lead to deep aesthetic insights. In Nature (1836), Emerson argues that “nature is a discipline;” rather than merely an inert set of objects to behold, nature constitutes the entirety of that from which we derive our subjective experiences. By honing this discipline of nature, we may achieve a kind of enlightenment. Filmmakers like Hutton and Benning have, furthermore, been able to extend this practice of looking, through the technologies of cinema, into ever-new areas.

Sitney writes that in Hutton’s work, for example, “subtle fluctuations in the visible field—of light, or figures and objects in motion, or slight camera movements—configure the ecstatic concentration of the filmmaker’s attention.” [2] Benning himself may be echoing Emerson when he writes that “seeing is a discipline,” and has also favored a similar quote by Henry Thoreau: “No method nor discipline can supersede the necessity of being forever on the alert. What is a course of history, or philosophy, or poetry, no matter how well selected, or the best society, or the most admirable routine of life, compared with the discipline of looking at what is to be seen?”[

3]

Nathaniel Dorsky, another contemporary of Benning and Hutton’s, has spoken of this discipline of looking in spiritual terms—what he calls a “devotional cinema”—but one need not turn to religion to understand these artists’ shared reverence for the continued possibilities of the photographic image, both in its content and its materials, in its specific colors, light properties, and moods. Years before cinema’s birth, Emerson imagined that the sensory encounter with nature could itself be a form of philosophical engagement, a way to better understand the self. If technology has continued to create new augmentations to human sight, then, these artists suggest, we may still find new pathways to insight as well through these same means. But in order to discover this, to continue to think about our place in the landscape, we must, like good sailors, remain on watch.

Nature is a Discipline

24 January – 8 March 2015

Curated by Ed Halter

Miguel Abreu Gallery is pleased to announce the opening, on Saturday, January 24, of Nature is a Discipline, an exhibition of film and video works by James Benning and Peter Hutton at both gallery locations.

Internationally recognized as two of the most accomplished American filmmakers of their generation, Benning and Hutton have been making motion pictures since the early 1970s; up until just the past few years, both have primarily worked in 16mm. The two men have related interests in documenting our modern relationship to landscapes, both natural and manmade, but do so with distinct approaches and sensibilities that have evolved over the decades. Recently, they have each responded to the increased difficulties of working in small-gauge celluloid by turning to new technologies. Since 2009, Benning has abandoned film to create new moving-image work exclusively using video, ranging from high-definition cinematography to appropriated YouTube clips, while Hutton has begun transferring work produced on 16mm to digital formats for screening.

As a result of this shift to digital, both artists have begun making pieces intended for installation in galleries and museum spaces, in addition to new works for theatrical projection in cinemas. Nature is a Discipline presents three recent installations that will show for the first time in New York: Hutton’s At Sea(2004-07) and Three Landscapes (2013), and Benning's Tulare Road(2010).

At Seais a new iteration of Hutton's longform 16mm work of the same name, transformed into three looping channels that echo the tripartite structure of the earlier film. Hutton, himself a former seaman with the Merchant Marines, documents the life of a modern cargo ship through each of these sections, from a ship’s construction in a South Korean port, to frosty journeys across the northern Atlantic, to workers disassembling a rusting ship for scrap on the shores of the Indian Ocean. Three Landscapes is also composed of three parts, but here the sections play off one another in ways more comparative than narrative. Each channel examines groups of laborers in vastly different locales: salt miners in the deserts of Ethiopia, farm workers in the green Hudson Valley, and bridge repairmen in post-industrial Detroit. As with Hutton’s 16mm films, both At Seaand Three Landscapesare projected silently, allowing for a deeper engagement with their remarkable sense of composition and elegantly unhurried pace.

Benning shot Tulare Road on a highway in California's Central Valley, an area that the director had previously explored in his film El Valley Centro (2000). Here, the only part of the SoCal landscape pictured is a lonely stretch of road extending to a distant horizon. Shot three times and presented on three adjoining channels, each version displays an almost identical composition of land and road under different weather formations, from dense fog to cloudy blue skies. The startling clarity of HD video plays against the landscape’s eerie stillness, broken intermittently by the rising and falling roar of passing cars or trucks. While Benning has always gravitated towards a kind of minimalism in his filmmaking, his work in the last decade has, at times, become ever more formally attenuated, and Tulare Roadcontinues his interest in the extended long take framed by a fixed camera, here enhanced by the repetition of the multiple channels and their infinite looping. “I have an interest in exploring space-time relationships through film,” Benning has stated. “There’s real time, and there’s how we perceive time.

Time affects the way we perceive place. That’s where I get this idea of ‘looking and listening.’ In my films, I’m very aware of recording place over time, and the way that makes you understand place. Once you’ve been watching something for a while, you become aware of it differently.”[1]

Writing on At Sea's theatrical version for Artforum, P. Adams Sitney argued that Hutton’s work is exemplary of the longstanding influence of Emersonian ideas on the American avant-garde cinema, particularly Emerson’s belief that we can teach ourselves to experience the world, through looking, in ways that can lead to deep aesthetic insights. In Nature (1836), Emerson argues that “nature is a discipline;” rather than merely an inert set of objects to behold, nature constitutes the entirety of that from which we derive our subjective experiences. By honing this discipline of nature, we may achieve a kind of enlightenment. Filmmakers like Hutton and Benning have, furthermore, been able to extend this practice of looking, through the technologies of cinema, into ever-new areas.

Sitney writes that in Hutton’s work, for example, “subtle fluctuations in the visible field—of light, or figures and objects in motion, or slight camera movements—configure the ecstatic concentration of the filmmaker’s attention.” [2] Benning himself may be echoing Emerson when he writes that “seeing is a discipline,” and has also favored a similar quote by Henry Thoreau: “No method nor discipline can supersede the necessity of being forever on the alert. What is a course of history, or philosophy, or poetry, no matter how well selected, or the best society, or the most admirable routine of life, compared with the discipline of looking at what is to be seen?”[

3]

Nathaniel Dorsky, another contemporary of Benning and Hutton’s, has spoken of this discipline of looking in spiritual terms—what he calls a “devotional cinema”—but one need not turn to religion to understand these artists’ shared reverence for the continued possibilities of the photographic image, both in its content and its materials, in its specific colors, light properties, and moods. Years before cinema’s birth, Emerson imagined that the sensory encounter with nature could itself be a form of philosophical engagement, a way to better understand the self. If technology has continued to create new augmentations to human sight, then, these artists suggest, we may still find new pathways to insight as well through these same means. But in order to discover this, to continue to think about our place in the landscape, we must, like good sailors, remain on watch.