Nicolás Guagnini

28 Jun - 11 Aug 2012

Sequence 4, one work, one week

NICOLÁS GUAGNINI

Seven

28 June – 11 August 2012

Miguel Abreu Gallery and Balice Hertling & Lewis are pleased to announce the opening, on Thursday, June 28th , of Sequence 4: Nicolás Guagnini,Seven, the fourth iteration of the gallery’s more or less annual Sequence exhibition in which a single work is installed in the space and replaced each week by another for the duration of the show.

In this version of the exhibition, Nicolás Guagnini will present, in two New York galleries located in distinct neighborhoods —Hell’s Kitchen and the Lower East Side — a continuum of seven quasi white on white paintings. The almost indistinguishable works comprising this open series stage the same famous slogan written on a Paris street corner in the early 1950s, and will circulate between the two locations until August 11th . Each painting is titled Work, and numbered 1 through 7.

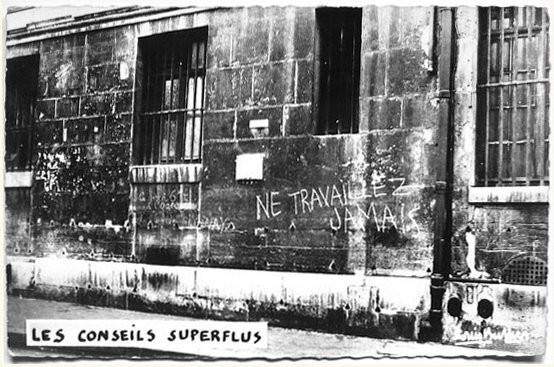

The paintings represent a photographic image only made decipherable as such when the viewer identifies an inscription. The image is a crop of acontroversial postcard of a Paris building wall marked by the Situationist graffiti, “NE TRAVAILLEZ JAMAIS.” The writing was probably executed with chalk by theorist, filmmaker, activist and cultural critic Guy Debord.

In 1963, Debord received a letter from the Cercle de la Librarie demanding payment for copyright infringement on behalf of a publisher named Baffier. As in fact he had, Debord was accused of lifting the photograph of the graffiti published in the journal Internationale Situationniste from one of a series of postcards of Parisian scenes with “funny” captions. However, in a brilliantly crafted response, Debord argued that since he was theauthor of the original inscription of the slogan (something for which he claimed hecould produce several witnesses), it was in fact the photographer and the publisher who had infringed on his authorship. Rejecting the whole of intellectual property law, Debord magnanimously proposed that he would not press charges. The phrase itself went on to become one of the most remembered slogans of May 68.

“Ne travaillez jamais” is celebrated, oft-repeated, yet has proved difficult to place into effective circulation — despite (or rather maybe because) of its strange familiarity. Ironically, the Situationist critique of labor doesn’t function any longer, as the whole of the S.I. can be said to have been reified into a cultural totem, the business of Art History departments, and footnotes in exhibition catalogues, a defined unit of value in the knowledge economy. The sequence of seven works presented in this exhibition, moreover, attempt to put the phrase into circulation anew by way of painting, the one locus, to be sure, where the Situationist proscription should not, cannot, and will not circulate. The space of meaning and object production claimed by Guagnini’s works and the specific spatial and temporal design for their marketing seem to systematically cover all the grounds for expulsion from the S.I.

The rotation of the paintings between the two galleries sets up one order of circulation. Yet another would be the one connecting Debord’s actual inscription on the wall of the rue de Seine, Baffier’s postcard of the graffiti, the recuperation and publication of a cropped version of the postcard in Internationale Situationiste #8, and Guagnini’s paintings featuring an even slightly more reductive crop. The paintings further reduce the image as they oscillate between monochromes and duotones. Their spatial and planar ambiguity is obtained by overlaying transparencies of white, silver and gray.

Given that these pictures are near monochromes and nearly identical, more questions are raised: is the monochromeready made, in popular imagination, not a classic case of ‘not enough work,’ bordering on never, on no work at all? Isn’t the gesture of repeating the same formula historically situated at the intersection between painting and Conceptual art, as demarcated by the work of On Kawara and Roman Opalka, or by Daniel Buren’s attempt at a zero degree of painting, another refusal to effectively work? The Situationist project of the “abolition du travail aliéné” (abolition of alienated work)aimed at terminating capitalist labor in favor of new forms of activity that could be seen either as the negation of work or as its transformation — a transformation to such a point that the distinction between work and non-work would become almost inconsequential. As it turns out years later, however, our actual new labor can be well described as the result of a temporal economy in which travaillez toujours (always work) might as well be the motto.

As Sven Lüttiken writes in ‘General Performance,’ his probing essay recently published on e-flux, which has informed much of the present text, “Ne travaillez jamais as ephemeral graffito was beyond recuperation, hardly an oeuvre. But as a postcard, subsequently detourned by the S.I., the piece became work, was put to work. Perhaps Debord succeeded in getting the publisher to discontinue the card, but in reprinting the photo (albeit cropped, shorn of its offensive caption) and engaging in a correspondence that has now been published as part of his Correspondence, Debord assisted in its transformation. In reappropiating his un-oeuvre and engaging in this legal game with the publisher, Debord effectively participated in the redefinition of work, performing intellectual or immaterial labor. His act, in other words, did not result in some hypothetical complete break with capitalism, but played the game in such a way that its contradictions were pushed to the limit, to a point where performing the new labor becomes, perhaps, an act—one of the ‘new forms of action in politics and art’ that Debord promised.” By blatantly placing the slogan back into the frame of art through its excluded major category of late modernist painting, Guagnini might be furthering this intricate line of work.

One of the most glaring allegorical effects to be considered here, finally, might simply be the one offered by the emptied out galleries in which apparently little work is being conducted for and during the proverbial summer group show.

In his work to date, Guagnini has thematized and explored the transformation of labor in the production, consumption and distribution of artworks, occupying the positions of artist, curator, dealer, teacher, craftsman, critic,and at times collector.

NICOLÁS GUAGNINI

Seven

28 June – 11 August 2012

Miguel Abreu Gallery and Balice Hertling & Lewis are pleased to announce the opening, on Thursday, June 28th , of Sequence 4: Nicolás Guagnini,Seven, the fourth iteration of the gallery’s more or less annual Sequence exhibition in which a single work is installed in the space and replaced each week by another for the duration of the show.

In this version of the exhibition, Nicolás Guagnini will present, in two New York galleries located in distinct neighborhoods —Hell’s Kitchen and the Lower East Side — a continuum of seven quasi white on white paintings. The almost indistinguishable works comprising this open series stage the same famous slogan written on a Paris street corner in the early 1950s, and will circulate between the two locations until August 11th . Each painting is titled Work, and numbered 1 through 7.

The paintings represent a photographic image only made decipherable as such when the viewer identifies an inscription. The image is a crop of acontroversial postcard of a Paris building wall marked by the Situationist graffiti, “NE TRAVAILLEZ JAMAIS.” The writing was probably executed with chalk by theorist, filmmaker, activist and cultural critic Guy Debord.

In 1963, Debord received a letter from the Cercle de la Librarie demanding payment for copyright infringement on behalf of a publisher named Baffier. As in fact he had, Debord was accused of lifting the photograph of the graffiti published in the journal Internationale Situationniste from one of a series of postcards of Parisian scenes with “funny” captions. However, in a brilliantly crafted response, Debord argued that since he was theauthor of the original inscription of the slogan (something for which he claimed hecould produce several witnesses), it was in fact the photographer and the publisher who had infringed on his authorship. Rejecting the whole of intellectual property law, Debord magnanimously proposed that he would not press charges. The phrase itself went on to become one of the most remembered slogans of May 68.

“Ne travaillez jamais” is celebrated, oft-repeated, yet has proved difficult to place into effective circulation — despite (or rather maybe because) of its strange familiarity. Ironically, the Situationist critique of labor doesn’t function any longer, as the whole of the S.I. can be said to have been reified into a cultural totem, the business of Art History departments, and footnotes in exhibition catalogues, a defined unit of value in the knowledge economy. The sequence of seven works presented in this exhibition, moreover, attempt to put the phrase into circulation anew by way of painting, the one locus, to be sure, where the Situationist proscription should not, cannot, and will not circulate. The space of meaning and object production claimed by Guagnini’s works and the specific spatial and temporal design for their marketing seem to systematically cover all the grounds for expulsion from the S.I.

The rotation of the paintings between the two galleries sets up one order of circulation. Yet another would be the one connecting Debord’s actual inscription on the wall of the rue de Seine, Baffier’s postcard of the graffiti, the recuperation and publication of a cropped version of the postcard in Internationale Situationiste #8, and Guagnini’s paintings featuring an even slightly more reductive crop. The paintings further reduce the image as they oscillate between monochromes and duotones. Their spatial and planar ambiguity is obtained by overlaying transparencies of white, silver and gray.

Given that these pictures are near monochromes and nearly identical, more questions are raised: is the monochromeready made, in popular imagination, not a classic case of ‘not enough work,’ bordering on never, on no work at all? Isn’t the gesture of repeating the same formula historically situated at the intersection between painting and Conceptual art, as demarcated by the work of On Kawara and Roman Opalka, or by Daniel Buren’s attempt at a zero degree of painting, another refusal to effectively work? The Situationist project of the “abolition du travail aliéné” (abolition of alienated work)aimed at terminating capitalist labor in favor of new forms of activity that could be seen either as the negation of work or as its transformation — a transformation to such a point that the distinction between work and non-work would become almost inconsequential. As it turns out years later, however, our actual new labor can be well described as the result of a temporal economy in which travaillez toujours (always work) might as well be the motto.

As Sven Lüttiken writes in ‘General Performance,’ his probing essay recently published on e-flux, which has informed much of the present text, “Ne travaillez jamais as ephemeral graffito was beyond recuperation, hardly an oeuvre. But as a postcard, subsequently detourned by the S.I., the piece became work, was put to work. Perhaps Debord succeeded in getting the publisher to discontinue the card, but in reprinting the photo (albeit cropped, shorn of its offensive caption) and engaging in a correspondence that has now been published as part of his Correspondence, Debord assisted in its transformation. In reappropiating his un-oeuvre and engaging in this legal game with the publisher, Debord effectively participated in the redefinition of work, performing intellectual or immaterial labor. His act, in other words, did not result in some hypothetical complete break with capitalism, but played the game in such a way that its contradictions were pushed to the limit, to a point where performing the new labor becomes, perhaps, an act—one of the ‘new forms of action in politics and art’ that Debord promised.” By blatantly placing the slogan back into the frame of art through its excluded major category of late modernist painting, Guagnini might be furthering this intricate line of work.

One of the most glaring allegorical effects to be considered here, finally, might simply be the one offered by the emptied out galleries in which apparently little work is being conducted for and during the proverbial summer group show.

In his work to date, Guagnini has thematized and explored the transformation of labor in the production, consumption and distribution of artworks, occupying the positions of artist, curator, dealer, teacher, craftsman, critic,and at times collector.