Olav Westphalen

16 Aug - 22 Sep 2007

OLAV WESTPHALEN

"The Big White"

Etymologists tell us there are about one hundred years separating the appearance

of the Middle English words seli and flipergebet. People began using seli as early as

1375. Seventy-eight years later, when Constantinople fell to the Muslims, overland trade routes to Asia became increasingly precarious. What do seli, flipergebet, and trade routes have to do with one another? Read on.

Looking for a new way east Bartolomeo, Giovanni Pelligrino, Giacomo and

Christopher, the Columbus brothers, decided to establish a trade route by sailing west across the Ocean Sea. When in 1492, Christopher set off across what we now call the Atlantic Ocean the Columbus brothers expected him to land in the Indies, but instead he discovered the new world. Those who spoke Middle English and suspected his voyage was at best imprudent, if not reckless, would likely have called Columbus a flipergebet but they would never have called him seli. Back then flipergebet meant pretty much what its modern version “flibbertigibbet” means today which is someone who is foolish or scatterbrained. But in the fifteenth century seli was the almost reverent description of someone “blessed and innocent,” which was a far cry from Christopher the flipergebet.

In time, seli became the word “silly” sharing more and more of the original meaning of flipergebet. You know what silly means. People who intend to discover something unheard of are subject to being called silly more often than the rest of us; the scientists who claimed to have invented cold-fusion were undoubtedly called silly at some point. If the word had existed in 1492 Christopher would have been silly on top of being flipergebet. Reading the critics that reviewed Olav Westphalen’s exhibitions you have the impression that they are tempted to call him silly but no one has had the guts to do it. What they have called him is slightly more respectable: oddball, outlandish, anti-idealist, a tester of limits, a maker of merriment, a comedian, anti-authoritarian and cartoonish.

Then they sprinkle in the dash of art history learned since the last art fair, corral him with the likes of Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley, and that’s that. My foretaste for Westphalen runs towards Francis Picaba, Martin Kippenberger, Michael Smith, and Walter Robinson but that’s another story.

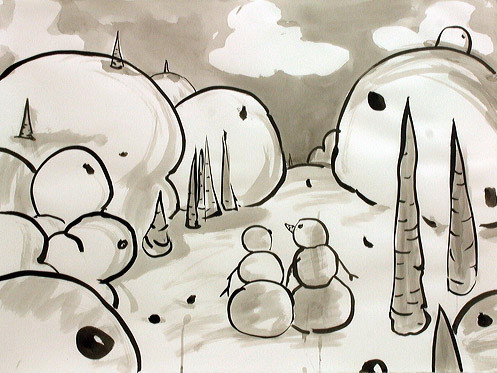

Westphalen’s exhibition at the Milliken Gallery is of drawings and sculptures of

snowmen. He places these ephemeral characters in all sorts of droll but topical mise-enscènes; one drawing is a stand-up comic snowman, another is definitely a snowwoman in the midst of childbirth, and he even touches on the fragility of our planet by showing us snow-people, each on a floating piece of the artic as its breaks up, presumably from the effects of global warming. “What’s the meaning of life,” Westphalen asks “when all you can say for sure is that you are bound to melt?” This is Westphalen at his flibbertigibbetbest trying to renegotiate art’s relation to entertainment and give it relevance to a wider audience. It’s what Andy Warhol did with his helium inflated silver pillows or Disaster Series when asking the big questions became as laudable as silly. The centerpiece of the exhibition is something else again. This is an installation where three snowmen slump against the gallery’s walls around a large column. Since snowmen dress pretty much alike it’s virtually impossible to index them socially or economically; these guys could live on the street around a public sculpture, or are they tourists suffering from Stendhal’s syndrome, or perhaps we see aesthetites lost in reverie? The ambiguity built into this scene evinces an atmosphere of humanity that opens a path towards empathy without all the jollity. Whoever they are, whatever they are doing they deserved to be called seli, blessed and innocent.

Ronald Jones

August 2007

"The Big White"

Etymologists tell us there are about one hundred years separating the appearance

of the Middle English words seli and flipergebet. People began using seli as early as

1375. Seventy-eight years later, when Constantinople fell to the Muslims, overland trade routes to Asia became increasingly precarious. What do seli, flipergebet, and trade routes have to do with one another? Read on.

Looking for a new way east Bartolomeo, Giovanni Pelligrino, Giacomo and

Christopher, the Columbus brothers, decided to establish a trade route by sailing west across the Ocean Sea. When in 1492, Christopher set off across what we now call the Atlantic Ocean the Columbus brothers expected him to land in the Indies, but instead he discovered the new world. Those who spoke Middle English and suspected his voyage was at best imprudent, if not reckless, would likely have called Columbus a flipergebet but they would never have called him seli. Back then flipergebet meant pretty much what its modern version “flibbertigibbet” means today which is someone who is foolish or scatterbrained. But in the fifteenth century seli was the almost reverent description of someone “blessed and innocent,” which was a far cry from Christopher the flipergebet.

In time, seli became the word “silly” sharing more and more of the original meaning of flipergebet. You know what silly means. People who intend to discover something unheard of are subject to being called silly more often than the rest of us; the scientists who claimed to have invented cold-fusion were undoubtedly called silly at some point. If the word had existed in 1492 Christopher would have been silly on top of being flipergebet. Reading the critics that reviewed Olav Westphalen’s exhibitions you have the impression that they are tempted to call him silly but no one has had the guts to do it. What they have called him is slightly more respectable: oddball, outlandish, anti-idealist, a tester of limits, a maker of merriment, a comedian, anti-authoritarian and cartoonish.

Then they sprinkle in the dash of art history learned since the last art fair, corral him with the likes of Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley, and that’s that. My foretaste for Westphalen runs towards Francis Picaba, Martin Kippenberger, Michael Smith, and Walter Robinson but that’s another story.

Westphalen’s exhibition at the Milliken Gallery is of drawings and sculptures of

snowmen. He places these ephemeral characters in all sorts of droll but topical mise-enscènes; one drawing is a stand-up comic snowman, another is definitely a snowwoman in the midst of childbirth, and he even touches on the fragility of our planet by showing us snow-people, each on a floating piece of the artic as its breaks up, presumably from the effects of global warming. “What’s the meaning of life,” Westphalen asks “when all you can say for sure is that you are bound to melt?” This is Westphalen at his flibbertigibbetbest trying to renegotiate art’s relation to entertainment and give it relevance to a wider audience. It’s what Andy Warhol did with his helium inflated silver pillows or Disaster Series when asking the big questions became as laudable as silly. The centerpiece of the exhibition is something else again. This is an installation where three snowmen slump against the gallery’s walls around a large column. Since snowmen dress pretty much alike it’s virtually impossible to index them socially or economically; these guys could live on the street around a public sculpture, or are they tourists suffering from Stendhal’s syndrome, or perhaps we see aesthetites lost in reverie? The ambiguity built into this scene evinces an atmosphere of humanity that opens a path towards empathy without all the jollity. Whoever they are, whatever they are doing they deserved to be called seli, blessed and innocent.

Ronald Jones

August 2007