Reynaldo Rivera

Fistful of Love/También la belleza

16 May - 09 Sep 2024

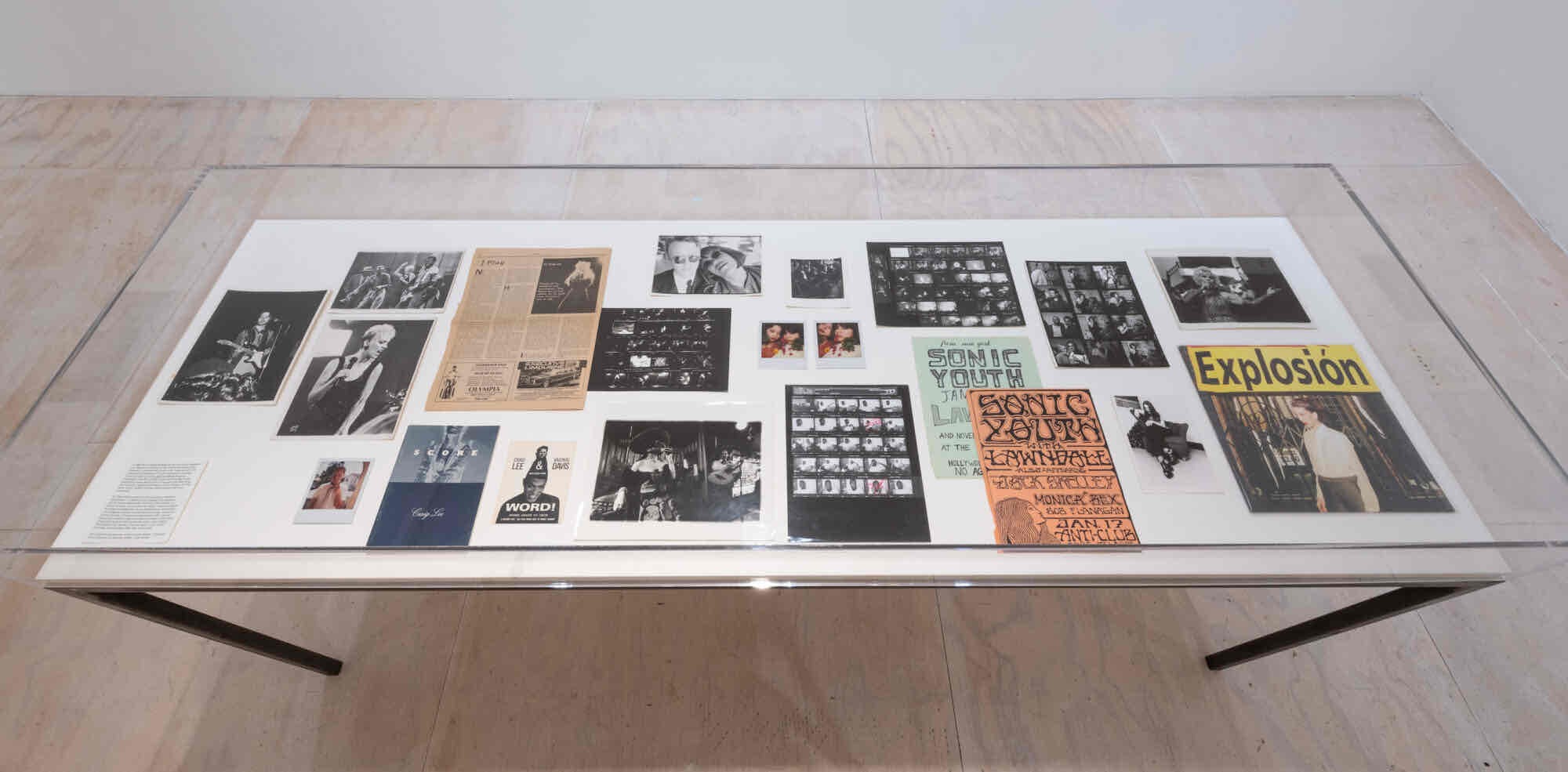

Installation view of Reynaldo Rivera: Fistful of Love/También la belleza, on view at MoMA PS1 from May 16 through September 9, 2024. Photo: Adam Reich

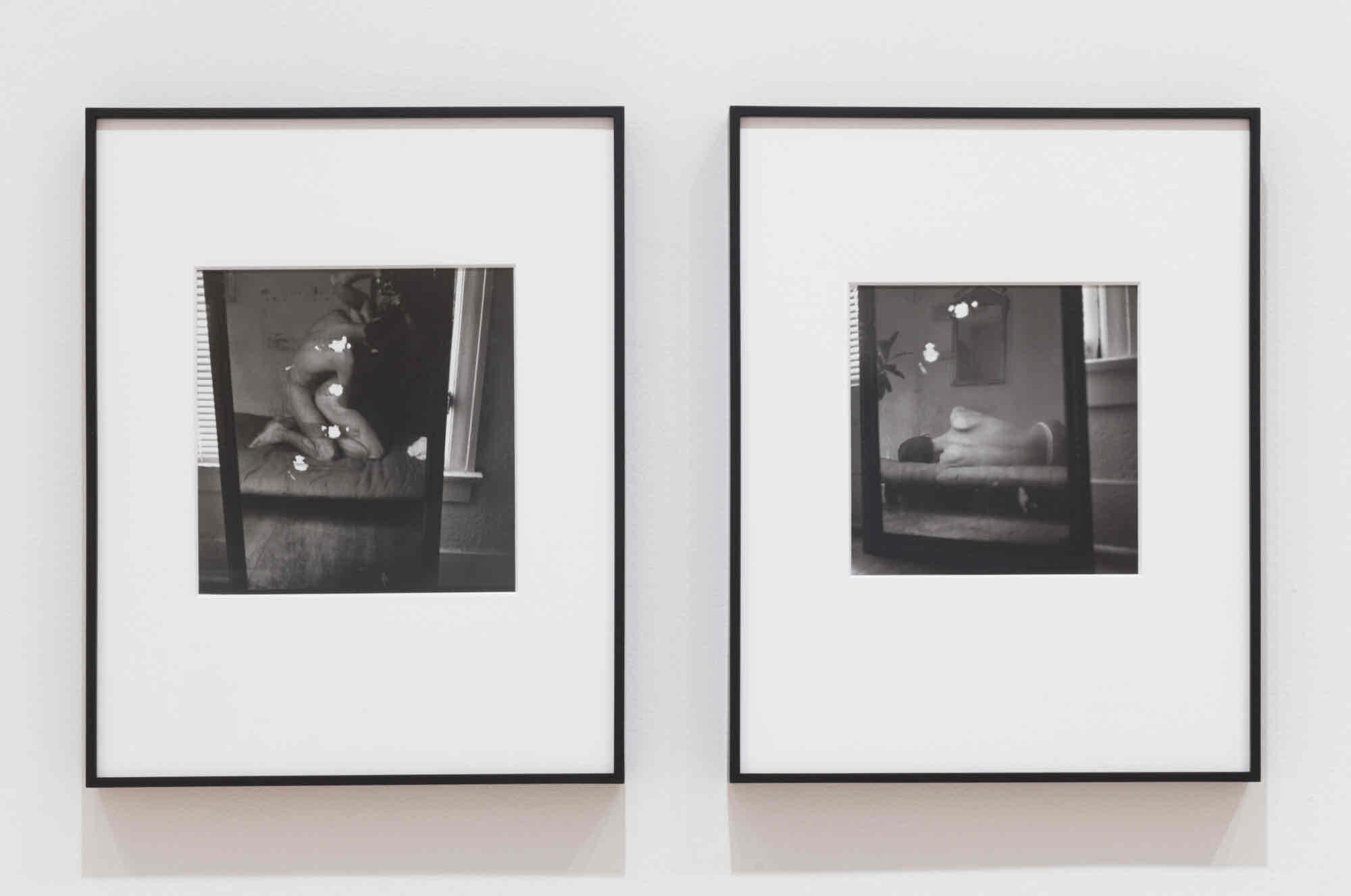

Installation view of Reynaldo Rivera: Fistful of Love/También la belleza, on view at MoMA PS1 from May 16 through September 9, 2024. Photo: Adam Reich

Installation view of Reynaldo Rivera: Fistful of Love/También la belleza, on view at MoMA PS1 from May 16 through September 9, 2024. Photo: Adam Reich

Installation view of Reynaldo Rivera: Fistful of Love/También la belleza, on view at MoMA PS1 from May 16 through September 9, 2024. Photo: Adam Reich

Installation view of Reynaldo Rivera: Fistful of Love/También la belleza, on view at MoMA PS1 from May 16 through September 9, 2024. Photo: Adam Reich

From left: Reynaldo Rivera. Bianco, Echo Park. 1992/2023. Silver gelatin print. Bianco, Reynaldo, Echo Park. 1992/2023. Silver gelatin print. Installation view of Reynaldo Rivera: Fistful of Love/También la belleza, on view at MoMA PS1 from May 16 through September 9, 2024. Photo: Adam Reich

This spring, MoMA PS1 presents the first solo museum exhibition of artist Reynaldo Rivera (b. 1964, Mexicali, Mexico), including iconic works and never-before-seen photographs from his archive. On view from May 16 through September 9, Reynaldo Rivera: Fistful of Love/También La belleza features fifty artworks, comprised of black-and-white and color photographs from 1981 to the present, a feature-length film newly edited from archival Hi8 footage, and ephemera. The artist’s pictures of an everyday intercultural bohemia—whether staged or captured behind the scenes—reveal their subjects as they desire to be seen: as stars in a film of their own making.

Raised between Mexicali, Stockton, Pasadena, and San Diego de la Unión, Rivera eventually settled in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles and into the artistic and activist milieu emerging around post-punk in the 1980s. As a self-taught photographer, Rivera first turned his camera to those close to him, including his sisters, who remained muses for decades. Working predominantly in black and white, the artist rinsed his earliest prints in a converted dark room, where his bathtub doubled as a developing tray. Rivera’s photographs are often made with available light—both natural and artificial—a technique that indirectly emphasizes the details of social environments he depicts, making use of spotlights at the Anti-Club, vanity lights backstage, birthday candles on cake, and street lamps on Santee Alley. His approach to image-making is informed by the drama and deep emotion of boleros and rancheras, the glamour of Old Hollywood and the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, and predecessors like Nadar, Brassaï, and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Rivera’s photographs portray friends and rivals, lovers and paramours, cousins and confidants across the LA music scene, riotous house parties, improvised fashion editorials, and a string of queer clubs (La Plaza, Le Bar, The Silverlake Lounge). Some of this trove was regularly published by the alternative newspaper LA Weekly, or else circulated in periodicals and printed matter, as headshots and on posters. Occasionally exhibited in galleries, distributed freely to friends, and lining the walls of his home, Rivera’s photographs also recur in the background of dinner parties and other late-night gatherings, indexing the world he created in real time. The artist uses photographic conventions to frame a perspective at odds with the broader cultural essentialism of the 1990s, providing a trace—both irreverent and romantic—of life at the end of the twentieth century.

Rivera’s latest work includes portraits of younger artists and new friends, alongside analog and digital prints from his vast archive. The process of reevaluation divulges the vicissitudes of the intervening years: burned negatives salvaged from multiple fires; photographs ripped up by a scorned lover; and friends lost to addiction, AIDS, and other hardships who return with a haunting vivacity. Also on view is a selection of prints not previously intended for public view: a“blue” series showing his closest subjects in various states of undress. That Rivera, too, is often reflected within the image frame both implicates him in these scenes and suggests that his various bodies of work compose a self-portrait—with and through others.

Many of Rivera’s subjects died prematurely; as the survivors weather the years, they commingle with a growing circle of poets, singers, writers, and actors ready to pose for his camera. Embracing the beauty in decay and the humility of aging, his photographs confront life and death candidly—in a style indebted to oral storytelling traditions, which Rivera describes as “a way of leaving [behind] the stories of people that come and go.”

The exhibition is organized by Lauren Mackler, guest curator, and Kari Rittenbach, Assistant Curator, MoMA PS1.

Raised between Mexicali, Stockton, Pasadena, and San Diego de la Unión, Rivera eventually settled in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles and into the artistic and activist milieu emerging around post-punk in the 1980s. As a self-taught photographer, Rivera first turned his camera to those close to him, including his sisters, who remained muses for decades. Working predominantly in black and white, the artist rinsed his earliest prints in a converted dark room, where his bathtub doubled as a developing tray. Rivera’s photographs are often made with available light—both natural and artificial—a technique that indirectly emphasizes the details of social environments he depicts, making use of spotlights at the Anti-Club, vanity lights backstage, birthday candles on cake, and street lamps on Santee Alley. His approach to image-making is informed by the drama and deep emotion of boleros and rancheras, the glamour of Old Hollywood and the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, and predecessors like Nadar, Brassaï, and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Rivera’s photographs portray friends and rivals, lovers and paramours, cousins and confidants across the LA music scene, riotous house parties, improvised fashion editorials, and a string of queer clubs (La Plaza, Le Bar, The Silverlake Lounge). Some of this trove was regularly published by the alternative newspaper LA Weekly, or else circulated in periodicals and printed matter, as headshots and on posters. Occasionally exhibited in galleries, distributed freely to friends, and lining the walls of his home, Rivera’s photographs also recur in the background of dinner parties and other late-night gatherings, indexing the world he created in real time. The artist uses photographic conventions to frame a perspective at odds with the broader cultural essentialism of the 1990s, providing a trace—both irreverent and romantic—of life at the end of the twentieth century.

Rivera’s latest work includes portraits of younger artists and new friends, alongside analog and digital prints from his vast archive. The process of reevaluation divulges the vicissitudes of the intervening years: burned negatives salvaged from multiple fires; photographs ripped up by a scorned lover; and friends lost to addiction, AIDS, and other hardships who return with a haunting vivacity. Also on view is a selection of prints not previously intended for public view: a“blue” series showing his closest subjects in various states of undress. That Rivera, too, is often reflected within the image frame both implicates him in these scenes and suggests that his various bodies of work compose a self-portrait—with and through others.

Many of Rivera’s subjects died prematurely; as the survivors weather the years, they commingle with a growing circle of poets, singers, writers, and actors ready to pose for his camera. Embracing the beauty in decay and the humility of aging, his photographs confront life and death candidly—in a style indebted to oral storytelling traditions, which Rivera describes as “a way of leaving [behind] the stories of people that come and go.”

The exhibition is organized by Lauren Mackler, guest curator, and Kari Rittenbach, Assistant Curator, MoMA PS1.