Babi Badalov

To Make Art to Take Clothes Off

18 Feb - 04 Jun 2017

BABI BADALOV

To Make Art to Take Clothes Off

18 February - 4 June 2017

The barriers and edges of language, its meanings and its limits or the confusions and oppressive rules of language become a sort of visual poetry in the hands of Azerbaijani artist Babi Badalov (Lerik, Azerbaijan, 1959). In his work, almost always handcrafted, we come across linguistic constructs that unfold in drawings on paper or canvas, in collages and/or mural installations that form the core of an oeuvre that has also explored performance, poetic writing and other forms of artistic expression.

Text and image converge in his oeuvre in a unique contemporary adaptation of a traditional practice common in many different cultures like drawing and calligraphy. Not only on account of the materials, the relationship between the sign or image, and the space, the support or the semantic references of his work, but above all for the signifiant impulsive exploration that underlies his oeuvre as a whole. In fact, in his production, drawing and writing seem to refer to the same poetic horizon, which has a long tradition in all sorts of cultures that have linked these two seemingly disparate cultures. Writing didn"t only begin as pictography — calligraphy as an art was practiced in many cultures of the Middle East and Asia. Chinese and especially Japanese calligraphy have been appreciated for their aesthetic qualities. Arabic calligraphy is an important pillar of the art of Islamic cultures due to the prohibition of figurative representation. Illuminated mediaeval codices of Christianity like the Mozarabic Visigothic Bible of León dated 960 AD are but attempts to combine texts and images (occasionally confusing symbol and sign, as in the case of capital letters) that were subsequently further explored in mediaeval shaped poetry. This tradition has led to modern and contemporary experimental poetry in which the alphabet, text and image are fused and confused.

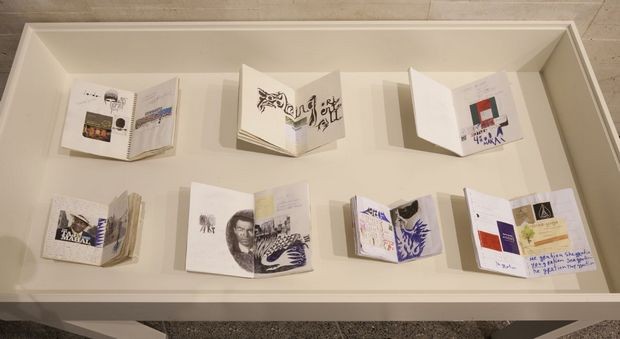

Sometimes written or drawn on fabrics in different sizes, at others on simple DIN A4 sheets or in notebooks where drawing and collage converge, occasionally drawn directly on the wall in large murals, very often with spelling "mistakes", almost always fragmented and direct and usually characterised by a personal horror vacui, Badalov"s works merge with the described traditions and expand them towards other territories like activism, political, gender, post-colonial, geostrategic readings, etc. He uses different alphabets and highly personal fonts that he combines with an apparent sense of humour under which lies an exploration of the language and the ideological, the social and political framework that supports it as a vehicle of communication. All languages express what is seen and said, but they also have aspects that are not seen and are always charged with ideology.

What is said and who says it are neither spontaneous nor free. Languages aren"t neutral, or are only so superficially. Under the words we use lie the conceptual structures that are often pure ideology. The work of Babi Badalov frequently focuses on linguistic explorations of inclusions and exclusions, ideologies and forms of domination, or the limits and borders of language that impose on their users selective ways of seeing the world expressed from the point of view of politics, gender, the social, culture or linguistics.

To Make Art to Take Clothes Off

18 February - 4 June 2017

The barriers and edges of language, its meanings and its limits or the confusions and oppressive rules of language become a sort of visual poetry in the hands of Azerbaijani artist Babi Badalov (Lerik, Azerbaijan, 1959). In his work, almost always handcrafted, we come across linguistic constructs that unfold in drawings on paper or canvas, in collages and/or mural installations that form the core of an oeuvre that has also explored performance, poetic writing and other forms of artistic expression.

Text and image converge in his oeuvre in a unique contemporary adaptation of a traditional practice common in many different cultures like drawing and calligraphy. Not only on account of the materials, the relationship between the sign or image, and the space, the support or the semantic references of his work, but above all for the signifiant impulsive exploration that underlies his oeuvre as a whole. In fact, in his production, drawing and writing seem to refer to the same poetic horizon, which has a long tradition in all sorts of cultures that have linked these two seemingly disparate cultures. Writing didn"t only begin as pictography — calligraphy as an art was practiced in many cultures of the Middle East and Asia. Chinese and especially Japanese calligraphy have been appreciated for their aesthetic qualities. Arabic calligraphy is an important pillar of the art of Islamic cultures due to the prohibition of figurative representation. Illuminated mediaeval codices of Christianity like the Mozarabic Visigothic Bible of León dated 960 AD are but attempts to combine texts and images (occasionally confusing symbol and sign, as in the case of capital letters) that were subsequently further explored in mediaeval shaped poetry. This tradition has led to modern and contemporary experimental poetry in which the alphabet, text and image are fused and confused.

Sometimes written or drawn on fabrics in different sizes, at others on simple DIN A4 sheets or in notebooks where drawing and collage converge, occasionally drawn directly on the wall in large murals, very often with spelling "mistakes", almost always fragmented and direct and usually characterised by a personal horror vacui, Badalov"s works merge with the described traditions and expand them towards other territories like activism, political, gender, post-colonial, geostrategic readings, etc. He uses different alphabets and highly personal fonts that he combines with an apparent sense of humour under which lies an exploration of the language and the ideological, the social and political framework that supports it as a vehicle of communication. All languages express what is seen and said, but they also have aspects that are not seen and are always charged with ideology.

What is said and who says it are neither spontaneous nor free. Languages aren"t neutral, or are only so superficially. Under the words we use lie the conceptual structures that are often pure ideology. The work of Babi Badalov frequently focuses on linguistic explorations of inclusions and exclusions, ideologies and forms of domination, or the limits and borders of language that impose on their users selective ways of seeing the world expressed from the point of view of politics, gender, the social, culture or linguistics.