Paul Pfeiffer

28 Sep 2008 - 11 Jan 2009

PAUL PFEIFFER

"Paul Pfeiffer. Monologue"

September 28, 2008 – January 11, 2009

MUSAC presents Paul Pfeiffer. Monologue . The acclaimed American artist’s first solo show in Spain

Exhibition title: Paul Pfeiffer. Monologue

Artist: Paul Pfeiffer

Curators: Octavio Zaya

Coordinator: Kristine Guzmán

Place: Halls 2.1 and 2.2

Dates: September 28, 2008 – January 11, 2009

MUSAC, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, presents Paul Pfeiffer. Monologue, the acclaimed American artist’s first one-person exhibition held in Spain. Through this show, and the monographic publication that accompanies it, MUSAC re-examines the complex and sophisticated work of a creator who represents an essential referent in the international art scene of the past decade.

MUSAC, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, holds Paul Pfeiffer’s first solo show at a Spanish institution. Conceived as a select overview of the artist’s production from the past decade, this exhibition, which also includes recently produced projects, examines some of the fundamental pillars of a body of work that is outstanding in the United States art scene, where it is among the most recognized and influential of its generation.

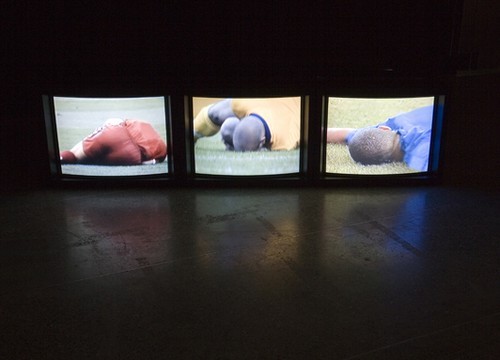

Paul Pfeiffer belongs to a generation of artists who have explored and experimented with the use of new technologies in a creative process that unfolds in media as diverse as video, installation, sculpture and photography. For his most widely recognized work, the artist digitally alters old film footage or T.V. sports events from which he eventually erases the main characters of the scenes, dissecting the role played by the mass media in the contemporary obsession and cult of celebrity. His installations are often unexpectedly small, and their technical means perfectly designed and conceived as part of the artwork. But what is striking is not only the elimination of the icon/star, but also the mass of spectators and the void upon which we project our anxieties and desires, especially those related to invisibility or the rejection represented by what we cannot attain, what escapes us. Hence, those references also point to the nearly religious spectacle of professional sports.

So Pfeiffer’s work is not limited to some kind of game of hide and-seek. The references and links in this work are sometimes as sophisticated as they are inscrutable. Horror films and Hitchcock’s movies are among Paul Pfeiffer’s main interests, and they serve as references for certain aspects of his creation. In pieces like 24 Landscapes (2000), the extensive beaches of the photographic series work as silent scenes that arouse our curiosity, perhaps because they are mute and empty images. We become archaeologists in search of traces and vestiges, in an effort to find something familiar. The photographs convey nothing about the invisibility or absence of the character, and we will only realize that there is something missing if we are familiar with the famous photographs George Barris took of Marilyn Monroe at the beach. Through digital imaging Pfeiffer meticulously retouched those photographs, displacing the true subject of the image –the star’s iconic body— and turning the background into the main theme, compelling us to concentrate on the dunes, the footprints and the cloud formations that we would otherwise have ignored or overlooked. Similarly, his series Three Studies of Figures at the Base of the Crucifixion (2001) –in the MUSAC collection—and Caryatid (2000) —whose respective departure points are the deletion of the leading players of a basketball game, and the isolation of one of its protagonists, with neither ball nor opponent— simultaneously address and situate us somewhere between suspense and virtually religious veneration, perhaps in order to provoke an experience that is never quite cathartic or completely comprehensible because its meaning, in silence, has already been lost, or we can only find it or recognize it in the frozen image that — as in the series The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (2004) desperately wishes to be, to be something more than a wax figure on the Olympus of obsolescence.

Pfeiffer undoubtedly finds expression for his obsessions among the recurrent myths of the United States, in the icons of mass culture that represent the “American dream” —basketball, boxing, Michael Jackson and Marilyn Monroe, the old and new promises of redemption and transcendence—, but in order to eliminate them, to express himself with their absence and through it. The erasure of the iconic body is predominant in his work. At first glance, when we no longer feel captivated by the omnipresence of that iconic image, what is manifested is an unexpected moment, of anxiety and doubt, as a mirror reflecting our own loss. We become part of the erased, absent image. Instead of captivatingly observing the icon, as viewers we look directly at the crowd watching the game in the sports stadium. At the same time, then, the spectator sees the very act of seeing. By “erasing” the icon Pfeiffer is therefore seeking to erase us, perhaps to liberate our identity and push us into the shapeless plural background of the crowd.

There is another aspect in Pfeiffer’s work wherein image and reality are transformed, but this time by probing the relation between appearance and real space. In this case, the appearance of reality seems more authentic than reality itself; or the copy is more likely than the original. Vertical Corridor (2005) oscillates between possibility and dystopia, in a sort of middle ground where the unbearable phantom of irresolution or of continual postponement of certainty may be lurking. An almost imperceptible opening in the wall enables us to look down an aseptic and unadorned corridor lit by neon lights, which seems to extend beyond the wall. We are actually looking through a periscope that affords us the illusion of seeing a space that stretches before us. The reality and the image we see both cancel each other out with no continuity and devoid of the hope they could have insinuated. In a certain way, this piece not only works as the ironic flipside of the modern less-is-more paradigm but also reflects the transformed appearance of Pfeiffer’s artwork: there is something missing; there is something that appears to be what it is not. As if the work always occupied two spaces that simultaneously complement and contradict each other.

Live from Neverland (2006) unmistakably operates in this doubling. Indeed, the piece consists of two elements. Through a screen, one of the two parts of the piece shows the statements from the famous televised interview in which Michael Jackson admits to having shared his bed with a group of children. The celebrated singer granted the interview after he was arrested and accused of sexual abuse, and during one of the most famous and widely reported trials in the United States. The second part is a large projection displaying the chorus of 80 students accurately reciting Michael Jackson’s confession in the manner of a Greek choir, organized and carefully arranged by the artist in the Philippines. The two videos are synchronized so that the voices of the chorus precisely coincide with the monologue that Jackson is gesturing on the mute, soundless monitor. In this piece, the transference and twist that the artist reveals to us openly demonstrate the ventriloquist nature Pfeiffer traces between the audience and celebrity, underscoring the exchanges, repetitions and substitutions that never fully capture the complex universe of recognitions, identifications and projections wherein the visual culture Pfeiffer reflects on is unfolding.

In contrast to the elaborate artifice of these works, the exhibition includes two documentary pieces, Sunset Flash (2004) and Empire (2004). That contrast is made even more evident by the dominating presence of the projectors in both pieces, which somehow establish a certain amount of objectivity and distance in these works by Pfeiffer. Sunset Flash is like a homemade movie, shot in 16 mm film and projected via an elaborate looping mechanism. This piece can be considered an autobiographical work; the reunion of Paul Pfeiffer’s large family in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Its members —of German, Philippine and Navaho descent— are barely visible in the lower part of the frame while a spectacular sunset dominates the whole field of vision of the work. From time to time we see flashes going off when the relatives take snapshots of each other, as they come on and off screen, and one of them organizes the arrangement of the family group for the photo. At the end of the thirty-minute projection, the artist appears with his mother.

In parallel, opposite this work, Empire displays another family system, but this time without a loop. This piece records the “real time” of the creation of a wasps’ nest over the course of three months. Pfeiffer recorded the queen building her nest, laying her eggs and establishing her rule. On this occasion Pfeiffer nods to the homologous work by Warhol —in its sheer length— as well as the influential book by Hardt & Neri, which both represent different versions of hierarchal conformations in progress. But in addition to these obvious relationships, Sunset Flash and Empire differ owing to the nostalgic quality of the former, shot on 16 mm film, and the flat appearance of the webcam aesthetic of the latter. Nevertheless, considered side by side in the same exhibition space, they both irremediably allude to incompleteness and the impossibility and frustration of fulfilment; in the first case as regards its content, and in the second case relating to the unfathomable format (because we shall never be able to see the entire work).

In general, referring to Paul Pfeiffer’s work implies discussing transference, erasures and scales. In this sense, the work can be considered a sort of revelation process that leads to a reality heretofore hidden by and behind the image (icon). The trace of that image draws the eye toward what is omitted and concealed, involving the spectator who imagines a reality around an emptied, formless centre. Pfeiffer’s art dwells in that shifting of the gaze toward the sinister or the unexpected, where the camera often adopts a strange, inhuman or supernatural perspective that is always obtuse, part miniatures and part enlargements, twists and doublings. In works like Poltergeist (2001) Pfeiffer objectifies a film, and in others, such as Quod Nomen Mihi Est (1998) —which reproduces the room of Reagan, the little girl in the film The Exorcist— the object makes possible and encourages an almost filmic experience. This experience, however, become more complicated in Self-Portrait as a Fountain (2000) —which reproduces the famous shower from Hitchcock’s Pyscho. This “self-portrait” does not immediately or surreptitiously reveal the presence of the artist (as is the case of Hitchock’s furtive appearance in his films). On the contrary, it is in the gleaming between the references that summons his homage —as Pfeiffer also reflects in the book accompanying the exhibition— where we locate the distant and ever changing face of the artist, always present and always absent —like his erasures—, always everywhere and nowhere, in a constant slippage between the two. And it cannot be otherwise; Pfeiffer’s work is a monologue/portrait of absent and shifted realities that can never be completely realized.

In all these cases, as in those mentioned above, Pfeiffer situates us in an event/monologue-inprogress, which is above all an experience without a finished narrative and without feeling, because both of them —the narrative and the feeling respectively— belong to the domain of the manifest and the sensitive, whereas Pfeiffer’s ventriloquist event is but a driving force and guide that, conversely, is only manifested in its symptoms; as a representation and as feeling. In other words, the work explores a way of approaching what we cannot see through what we see, while it indefinitely postpones the resolution in a swaying to and fro that constantly shifts perception, and our perception, in a game that speculates between reality and fiction, by way of sophisticated references and invisibilities, obsessions and absences.

A brief biography of the artist

Born in 1966 in Honolulu, Hawaii (U.S.A.), Paul Pfeiffer spent most of his childhood in the Philippines, until he settled in New York in 1990. There, he studied at Hunter College, and later participated in the Whitney Independent Study Program. Since the beginning of his career, Pfeiffer has won numerous awards —including the first Bucksbuam Award (2000) at the Whitney Biennial— and scholarships —Massachusetts Institute of Technology and ArtPace. His work has been shown in numerous one-person shows, most noteworthy among which are those organized by the MIT List Visual Arts Center of Cambridge, Massachusetts; the Museum of Contemporary Art of Chicago; Artangel of London; K21 of Düsseldorf and the Kunst-Werke of Berlin. Pfeiffer was selected for the 49th Venice Biennale and more recently for the Sydney Biennial, 2008.

The publication

The exhibition is accompanied by a monographic publication, which also reviews Paul Pfeiffer’s artistic production over the past decade. The book, which is edited by the curator Octavio Zaya for MUSAC, is published by ACTAR Barcelona/New York, and designed by Li, Inc., New York. In addition to introducing us to the extensive work of this influential artist, the original essays by Lawrence Chua (writer and professor at the Architecture Department of Cornell University, New York), Jessica Hagedorn (writer, Philippines), Niklas Maak (critic and columnist for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) and Katy Siegel (Professor of Art History at Hunter College, and critic for Artforum), and other writings selected by the artist from among the works of Don Delillo, Ellias Canetti, Gary Indiana and Roger Caillois, shed light on the intricate universe in which Paul Pfeiffer’s complex mental process unfolds.

"Paul Pfeiffer. Monologue"

September 28, 2008 – January 11, 2009

MUSAC presents Paul Pfeiffer. Monologue . The acclaimed American artist’s first solo show in Spain

Exhibition title: Paul Pfeiffer. Monologue

Artist: Paul Pfeiffer

Curators: Octavio Zaya

Coordinator: Kristine Guzmán

Place: Halls 2.1 and 2.2

Dates: September 28, 2008 – January 11, 2009

MUSAC, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, presents Paul Pfeiffer. Monologue, the acclaimed American artist’s first one-person exhibition held in Spain. Through this show, and the monographic publication that accompanies it, MUSAC re-examines the complex and sophisticated work of a creator who represents an essential referent in the international art scene of the past decade.

MUSAC, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, holds Paul Pfeiffer’s first solo show at a Spanish institution. Conceived as a select overview of the artist’s production from the past decade, this exhibition, which also includes recently produced projects, examines some of the fundamental pillars of a body of work that is outstanding in the United States art scene, where it is among the most recognized and influential of its generation.

Paul Pfeiffer belongs to a generation of artists who have explored and experimented with the use of new technologies in a creative process that unfolds in media as diverse as video, installation, sculpture and photography. For his most widely recognized work, the artist digitally alters old film footage or T.V. sports events from which he eventually erases the main characters of the scenes, dissecting the role played by the mass media in the contemporary obsession and cult of celebrity. His installations are often unexpectedly small, and their technical means perfectly designed and conceived as part of the artwork. But what is striking is not only the elimination of the icon/star, but also the mass of spectators and the void upon which we project our anxieties and desires, especially those related to invisibility or the rejection represented by what we cannot attain, what escapes us. Hence, those references also point to the nearly religious spectacle of professional sports.

So Pfeiffer’s work is not limited to some kind of game of hide and-seek. The references and links in this work are sometimes as sophisticated as they are inscrutable. Horror films and Hitchcock’s movies are among Paul Pfeiffer’s main interests, and they serve as references for certain aspects of his creation. In pieces like 24 Landscapes (2000), the extensive beaches of the photographic series work as silent scenes that arouse our curiosity, perhaps because they are mute and empty images. We become archaeologists in search of traces and vestiges, in an effort to find something familiar. The photographs convey nothing about the invisibility or absence of the character, and we will only realize that there is something missing if we are familiar with the famous photographs George Barris took of Marilyn Monroe at the beach. Through digital imaging Pfeiffer meticulously retouched those photographs, displacing the true subject of the image –the star’s iconic body— and turning the background into the main theme, compelling us to concentrate on the dunes, the footprints and the cloud formations that we would otherwise have ignored or overlooked. Similarly, his series Three Studies of Figures at the Base of the Crucifixion (2001) –in the MUSAC collection—and Caryatid (2000) —whose respective departure points are the deletion of the leading players of a basketball game, and the isolation of one of its protagonists, with neither ball nor opponent— simultaneously address and situate us somewhere between suspense and virtually religious veneration, perhaps in order to provoke an experience that is never quite cathartic or completely comprehensible because its meaning, in silence, has already been lost, or we can only find it or recognize it in the frozen image that — as in the series The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (2004) desperately wishes to be, to be something more than a wax figure on the Olympus of obsolescence.

Pfeiffer undoubtedly finds expression for his obsessions among the recurrent myths of the United States, in the icons of mass culture that represent the “American dream” —basketball, boxing, Michael Jackson and Marilyn Monroe, the old and new promises of redemption and transcendence—, but in order to eliminate them, to express himself with their absence and through it. The erasure of the iconic body is predominant in his work. At first glance, when we no longer feel captivated by the omnipresence of that iconic image, what is manifested is an unexpected moment, of anxiety and doubt, as a mirror reflecting our own loss. We become part of the erased, absent image. Instead of captivatingly observing the icon, as viewers we look directly at the crowd watching the game in the sports stadium. At the same time, then, the spectator sees the very act of seeing. By “erasing” the icon Pfeiffer is therefore seeking to erase us, perhaps to liberate our identity and push us into the shapeless plural background of the crowd.

There is another aspect in Pfeiffer’s work wherein image and reality are transformed, but this time by probing the relation between appearance and real space. In this case, the appearance of reality seems more authentic than reality itself; or the copy is more likely than the original. Vertical Corridor (2005) oscillates between possibility and dystopia, in a sort of middle ground where the unbearable phantom of irresolution or of continual postponement of certainty may be lurking. An almost imperceptible opening in the wall enables us to look down an aseptic and unadorned corridor lit by neon lights, which seems to extend beyond the wall. We are actually looking through a periscope that affords us the illusion of seeing a space that stretches before us. The reality and the image we see both cancel each other out with no continuity and devoid of the hope they could have insinuated. In a certain way, this piece not only works as the ironic flipside of the modern less-is-more paradigm but also reflects the transformed appearance of Pfeiffer’s artwork: there is something missing; there is something that appears to be what it is not. As if the work always occupied two spaces that simultaneously complement and contradict each other.

Live from Neverland (2006) unmistakably operates in this doubling. Indeed, the piece consists of two elements. Through a screen, one of the two parts of the piece shows the statements from the famous televised interview in which Michael Jackson admits to having shared his bed with a group of children. The celebrated singer granted the interview after he was arrested and accused of sexual abuse, and during one of the most famous and widely reported trials in the United States. The second part is a large projection displaying the chorus of 80 students accurately reciting Michael Jackson’s confession in the manner of a Greek choir, organized and carefully arranged by the artist in the Philippines. The two videos are synchronized so that the voices of the chorus precisely coincide with the monologue that Jackson is gesturing on the mute, soundless monitor. In this piece, the transference and twist that the artist reveals to us openly demonstrate the ventriloquist nature Pfeiffer traces between the audience and celebrity, underscoring the exchanges, repetitions and substitutions that never fully capture the complex universe of recognitions, identifications and projections wherein the visual culture Pfeiffer reflects on is unfolding.

In contrast to the elaborate artifice of these works, the exhibition includes two documentary pieces, Sunset Flash (2004) and Empire (2004). That contrast is made even more evident by the dominating presence of the projectors in both pieces, which somehow establish a certain amount of objectivity and distance in these works by Pfeiffer. Sunset Flash is like a homemade movie, shot in 16 mm film and projected via an elaborate looping mechanism. This piece can be considered an autobiographical work; the reunion of Paul Pfeiffer’s large family in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Its members —of German, Philippine and Navaho descent— are barely visible in the lower part of the frame while a spectacular sunset dominates the whole field of vision of the work. From time to time we see flashes going off when the relatives take snapshots of each other, as they come on and off screen, and one of them organizes the arrangement of the family group for the photo. At the end of the thirty-minute projection, the artist appears with his mother.

In parallel, opposite this work, Empire displays another family system, but this time without a loop. This piece records the “real time” of the creation of a wasps’ nest over the course of three months. Pfeiffer recorded the queen building her nest, laying her eggs and establishing her rule. On this occasion Pfeiffer nods to the homologous work by Warhol —in its sheer length— as well as the influential book by Hardt & Neri, which both represent different versions of hierarchal conformations in progress. But in addition to these obvious relationships, Sunset Flash and Empire differ owing to the nostalgic quality of the former, shot on 16 mm film, and the flat appearance of the webcam aesthetic of the latter. Nevertheless, considered side by side in the same exhibition space, they both irremediably allude to incompleteness and the impossibility and frustration of fulfilment; in the first case as regards its content, and in the second case relating to the unfathomable format (because we shall never be able to see the entire work).

In general, referring to Paul Pfeiffer’s work implies discussing transference, erasures and scales. In this sense, the work can be considered a sort of revelation process that leads to a reality heretofore hidden by and behind the image (icon). The trace of that image draws the eye toward what is omitted and concealed, involving the spectator who imagines a reality around an emptied, formless centre. Pfeiffer’s art dwells in that shifting of the gaze toward the sinister or the unexpected, where the camera often adopts a strange, inhuman or supernatural perspective that is always obtuse, part miniatures and part enlargements, twists and doublings. In works like Poltergeist (2001) Pfeiffer objectifies a film, and in others, such as Quod Nomen Mihi Est (1998) —which reproduces the room of Reagan, the little girl in the film The Exorcist— the object makes possible and encourages an almost filmic experience. This experience, however, become more complicated in Self-Portrait as a Fountain (2000) —which reproduces the famous shower from Hitchcock’s Pyscho. This “self-portrait” does not immediately or surreptitiously reveal the presence of the artist (as is the case of Hitchock’s furtive appearance in his films). On the contrary, it is in the gleaming between the references that summons his homage —as Pfeiffer also reflects in the book accompanying the exhibition— where we locate the distant and ever changing face of the artist, always present and always absent —like his erasures—, always everywhere and nowhere, in a constant slippage between the two. And it cannot be otherwise; Pfeiffer’s work is a monologue/portrait of absent and shifted realities that can never be completely realized.

In all these cases, as in those mentioned above, Pfeiffer situates us in an event/monologue-inprogress, which is above all an experience without a finished narrative and without feeling, because both of them —the narrative and the feeling respectively— belong to the domain of the manifest and the sensitive, whereas Pfeiffer’s ventriloquist event is but a driving force and guide that, conversely, is only manifested in its symptoms; as a representation and as feeling. In other words, the work explores a way of approaching what we cannot see through what we see, while it indefinitely postpones the resolution in a swaying to and fro that constantly shifts perception, and our perception, in a game that speculates between reality and fiction, by way of sophisticated references and invisibilities, obsessions and absences.

A brief biography of the artist

Born in 1966 in Honolulu, Hawaii (U.S.A.), Paul Pfeiffer spent most of his childhood in the Philippines, until he settled in New York in 1990. There, he studied at Hunter College, and later participated in the Whitney Independent Study Program. Since the beginning of his career, Pfeiffer has won numerous awards —including the first Bucksbuam Award (2000) at the Whitney Biennial— and scholarships —Massachusetts Institute of Technology and ArtPace. His work has been shown in numerous one-person shows, most noteworthy among which are those organized by the MIT List Visual Arts Center of Cambridge, Massachusetts; the Museum of Contemporary Art of Chicago; Artangel of London; K21 of Düsseldorf and the Kunst-Werke of Berlin. Pfeiffer was selected for the 49th Venice Biennale and more recently for the Sydney Biennial, 2008.

The publication

The exhibition is accompanied by a monographic publication, which also reviews Paul Pfeiffer’s artistic production over the past decade. The book, which is edited by the curator Octavio Zaya for MUSAC, is published by ACTAR Barcelona/New York, and designed by Li, Inc., New York. In addition to introducing us to the extensive work of this influential artist, the original essays by Lawrence Chua (writer and professor at the Architecture Department of Cornell University, New York), Jessica Hagedorn (writer, Philippines), Niklas Maak (critic and columnist for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) and Katy Siegel (Professor of Art History at Hunter College, and critic for Artforum), and other writings selected by the artist from among the works of Don Delillo, Ellias Canetti, Gary Indiana and Roger Caillois, shed light on the intricate universe in which Paul Pfeiffer’s complex mental process unfolds.