The Marvelous Real

14 Sep 2013 - 05 Jan 2014

THE MARVELOUS REAL

The MUSAC Collection in the Dual Year Spain-Japan

14 September 2013 - 5 January 2014

Curatorship: Kristine Guzmán, Yuko Hasegawa, Hikari Odaka

Coordination: Koré Escobar

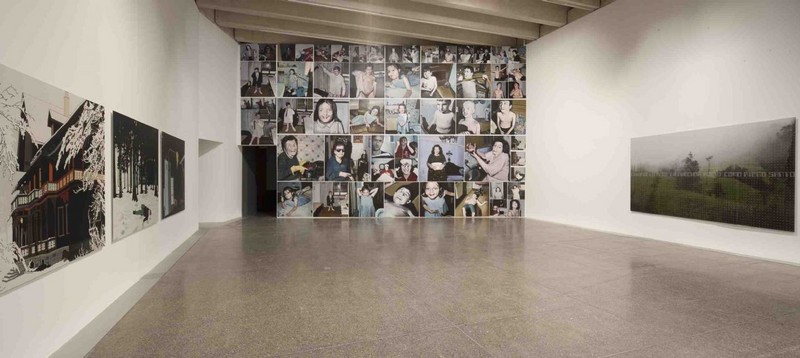

The Marvelous Real is an exhibition of works from the MUSAC Collection in collaboration with the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT). The show is within the framework of activities organized on occasion of the “Dual Year Spain–Japan” commemorating the 4th Centenary of the Keicho Embassy—first Japanese diplomatic mission to Spain—that left the Sendai region on October 1613 and arrived at Seville 12 months later. With the aim of fostering understanding between Japan and Spain and open new horizons in bilateral relations in the future, the dual year was inaugurated last June 11 in Madrid and will end in Tokyo on July 2014.

The title of the exhibition comes from the text On the Marvelous Real in America which Alejo Carpentier wrote in 1943 after a trip to Haiti, as a prologue to his novel The Kingdom of this World. In it, the author reflects on the richness of the Latin American continent and contrasts it with the rest of the world, where he discovers a complex and contradictory geography, where traditions, myths and heritage come together. And in this intent to search for this reality, Carpentier finds “the marvelous.”

The surrealists of the European Vanguards of those years searched for the magical in the artificial as something real. Carpentier, however, noted that in Latin America, the marvellous is present in daily life. It is in nature, in mankind, in history and does not require a conscious assault of a reality but an amplification of perceived reality. A reality that is expressed through mixed or reversed values and perspectives, which are characteristics of Latin America. The word “surrealismo” [“surrealism”] could be analyzed and reconstructed into “realismo del sur” [“southern realism”]; the surreal in north/west could be real in south. It is the case of Spain with the rest of Europe, or Latin America with the rest of the world.

That sort of reality derives from the desire to have a dialogue with the supernatural or the magical, by dragging them down to the earth as if they are tangible like some quotidian items. The expression often takes form of “exaggeration” of mundane scenery or things: “esperpento,” in the words of Ramón del Valle Inclán. It could even appear as a space filled with signs of reality, lacking any minute description of a subject.

And although this idea of “realismo del sur” is widely associated to Latin American cultures—after Carpentier, a new generation of writers emerged such as Gabriel García Márquez or Miguel Ángel Asturias—, it rarely finds its way into a country’s popular culture as it has in Japan. From centuries back, Shinto myths, legends or folktales often talk about the real and the supernatural, with the concept of “kami,” or gods, as a fundamental part of the Shinto religion. Through the passing of the years, however, traditional values in Japan have changed and with it, artistic expression. Thus, the changing modern values are expressed in this tension between reality and unreality, as can be seen in the works of authors Haruki Murakami or Banana Yoshitomo, or the filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki.

The resemblance in the grasp of this type of realism that can be perceived between the Japanese culture and ours is what has led to the idea of “the marvelous real” as the conductive thread of an exhibition of works that seek to reflect on the notions of the marvelous, the supernatural, the fantastic, fiction, parody, play and radical imagination as important ingredients of an artistic, social and political discourse. The role and understanding of the notion as well as the fluid relation between fiction and reality have undergone constant changes in the last few years, reflecting the new conditions of conflictive times and giving way to a series of pertinent, radical and necessary questions such as: What is the transformative power of fantasy and fiction? How do forms of playfulness affect or help manifestations of economic and political problems? What indeed constitutes imagination and reality? What part of reality is fantastic? What part of the fantasy is real? Are they so different?

The MUSAC Collection in the Dual Year Spain-Japan

14 September 2013 - 5 January 2014

Curatorship: Kristine Guzmán, Yuko Hasegawa, Hikari Odaka

Coordination: Koré Escobar

The Marvelous Real is an exhibition of works from the MUSAC Collection in collaboration with the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT). The show is within the framework of activities organized on occasion of the “Dual Year Spain–Japan” commemorating the 4th Centenary of the Keicho Embassy—first Japanese diplomatic mission to Spain—that left the Sendai region on October 1613 and arrived at Seville 12 months later. With the aim of fostering understanding between Japan and Spain and open new horizons in bilateral relations in the future, the dual year was inaugurated last June 11 in Madrid and will end in Tokyo on July 2014.

The title of the exhibition comes from the text On the Marvelous Real in America which Alejo Carpentier wrote in 1943 after a trip to Haiti, as a prologue to his novel The Kingdom of this World. In it, the author reflects on the richness of the Latin American continent and contrasts it with the rest of the world, where he discovers a complex and contradictory geography, where traditions, myths and heritage come together. And in this intent to search for this reality, Carpentier finds “the marvelous.”

The surrealists of the European Vanguards of those years searched for the magical in the artificial as something real. Carpentier, however, noted that in Latin America, the marvellous is present in daily life. It is in nature, in mankind, in history and does not require a conscious assault of a reality but an amplification of perceived reality. A reality that is expressed through mixed or reversed values and perspectives, which are characteristics of Latin America. The word “surrealismo” [“surrealism”] could be analyzed and reconstructed into “realismo del sur” [“southern realism”]; the surreal in north/west could be real in south. It is the case of Spain with the rest of Europe, or Latin America with the rest of the world.

That sort of reality derives from the desire to have a dialogue with the supernatural or the magical, by dragging them down to the earth as if they are tangible like some quotidian items. The expression often takes form of “exaggeration” of mundane scenery or things: “esperpento,” in the words of Ramón del Valle Inclán. It could even appear as a space filled with signs of reality, lacking any minute description of a subject.

And although this idea of “realismo del sur” is widely associated to Latin American cultures—after Carpentier, a new generation of writers emerged such as Gabriel García Márquez or Miguel Ángel Asturias—, it rarely finds its way into a country’s popular culture as it has in Japan. From centuries back, Shinto myths, legends or folktales often talk about the real and the supernatural, with the concept of “kami,” or gods, as a fundamental part of the Shinto religion. Through the passing of the years, however, traditional values in Japan have changed and with it, artistic expression. Thus, the changing modern values are expressed in this tension between reality and unreality, as can be seen in the works of authors Haruki Murakami or Banana Yoshitomo, or the filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki.

The resemblance in the grasp of this type of realism that can be perceived between the Japanese culture and ours is what has led to the idea of “the marvelous real” as the conductive thread of an exhibition of works that seek to reflect on the notions of the marvelous, the supernatural, the fantastic, fiction, parody, play and radical imagination as important ingredients of an artistic, social and political discourse. The role and understanding of the notion as well as the fluid relation between fiction and reality have undergone constant changes in the last few years, reflecting the new conditions of conflictive times and giving way to a series of pertinent, radical and necessary questions such as: What is the transformative power of fantasy and fiction? How do forms of playfulness affect or help manifestations of economic and political problems? What indeed constitutes imagination and reality? What part of reality is fantastic? What part of the fantasy is real? Are they so different?