Atlas

26 Oct 2010 - 28 Mar 2011

How to carry the world on one’s back?

Curator: Georges Didi-Huberman

26 November, 2010 - 28 March, 2011

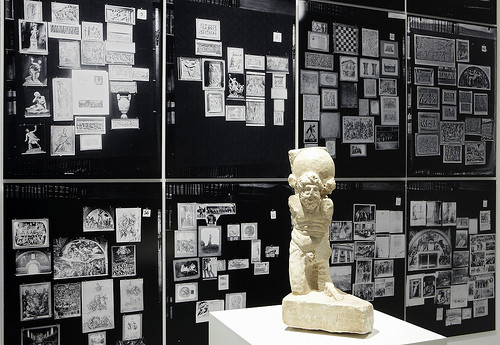

Starting from the Mnemosyne Atlas

Atlas is the name given in Greek mythology to a titan who, along with his brother Prometheus, contested the power of the gods of Olympus in order to make that power available to man. Legend has it that while Prometheus had his liver torn out by a vulture in the far East, Atlas was forced (in the West, between Andalusia and Morocco), to bear on his shoulders the weight of the celestial vault. It is also said, that from this weight he gained an unsurpassable knowledge of the world and an – albeit hopeless – wisdom. He is the ancestor of astronomers and geographers; some even say he was the first philosopher. He gave his name to a mountain (Mount Atlas), to an ocean (the Atlantic), and to an anthropomorphic architectural form (an atlas or atlantes) which is designed to support an entablature.

Atlas, finally, gave his name to a visual form of knowledge: a gathering of geographical maps in a volume, and more generally, a collection of images intended to bring before our eyes, in a systematic or problematic way – even a poetic way, at the risk of being erratic, if not surrealist – a whole multiplicity of things gathered there through elective affinities, to use the words of Goethe. The atlas of images became a scientific genre in itself in the 18th century (we can think of the plates of l’Encyclopèdie) and it developed considerably in the

19th and 20th centuries. There are very serious atlases, very useful atlases – which are often very beautiful – in the life sciences (for example, the collections by Ernst Haeckel on jelly fish and other marine animals); there are more hypothetical atlases (for example, in the domain of archaeology); there are absolutely detestable atlases in the fields of anthropology and psychology (for example, L’Atlas de l’homme criminel [The Atlas of the Criminal Man] by Cesare Lombroso, or certain collections of “racial” photographs made by some pseudo-scholars in the 19th century).

In the visual arts, the Mnemosyne Atlas of images, composed by Aby Warburg between 1924 and 1929, and yet left unfinished, remains for any art historian – and even for any artist today – a reference and an absolutely fascinating case-study. Warburg completely renewed our way of understanding images. He is to art history what Freud, his contemporary, is to psychology: he opened the understanding of art to radically new questions, those concerning unconscious memory in particular. Mnemosyne is his paradoxical masterpiece and his methodological testament: it gathers all of the objects of his research in an apparatus that is also a reaction to two fundamental experiences: that of madness, and that of war. It can therefore be considered a documentary history of the Western imagination (as such, the inheritor of the Disparates and the Caprichos of Goya) and as a tool for understanding the political violence of images in history (comparable, as such, to a collection of Desastres).

At the montage table

ATLAS. How to carry the world on one’s back? is an interdisciplinary exhibition which crosses the 20th and 21st centuries by taking the Mnemosyne Atlas as its point of departure. In spite of the differences of method and content which might separate the research of a historian-philosopher from the work of a visual artist, what is striking is their common heuristic — or experimental — method when based on a montage of heterogeneous images. We discover that Warburg shares with the artists of his time the same passion for an operating visual affinity, which makes him the contemporary of avant-garde artists (Kurt Schwitters or László Moholy-Nagy), of photographers of the “documentary style” (August Sander or Karl Blossfeldt), of avant- garde filmmakers (Dziga Vertov or Sergei Eisenstein), of writers who employed literary montage (Walter Benjamin or Benjamin Fondane), or even surrealist poets and artists (Georges Bataille or Man Ray).

The ATLAS exhibition was not conceived to bring together beautiful artifacts, but rather to understand how certain artists work – beyond the question of any masterpieces – and how this work can be considered from the perspective of an authentic method, and, even, a non-standard transverse knowledge of our world. You will not see, therefore, Paul Klee’s beautiful watercolours, but instead his modest herbarium and the graphic or theoretical ideas which came of it; you will not see Josef Albers’ modern squares, but instead his photographic album devoted to pre-Columbian architecture; you will not see Robert Rauschenberg’s immense tableaux, but instead a series of photographs uniting objects both modest and heterogeneous; you will not see the coloured splendours of Gerhard Richter, but a section of montages created for his ongoing Atlas; you will not see Sol LeWitt’s cubic structures, but instead his photographs of the walls of New York. In preference to the tableaux (the result of work) we have chosen, for this occasion, tables (as operating spaces, surfaces for play or for getting down to work). And we will have discovered in this way that the so-called “moderns” are no less subversive than the “post-moderns”, and that the latter are no less methodical and concerned with form than the “moderns”... This is a way of recounting the history of the visual arts outside academic art criticism’s historical and stylistic outlines.

Piecing together the order of things

When we arrange different images or different objects — playing cards, for example — on a table, we are free to modify constantly their configuration. We can make piles or constellations. We can discover new analogies, new trajectories of thought. By modifying the order, we can arrange things so that images take positions.

A table is not made for definitively classifying, for exhaustively making an inventory, or for cataloguing once and for all – as in a dictionary, an archive or an encyclopaedia – but instead for gathering segments, or parcelling out the world, while respecting its multiplicity and its heterogeneity — and for giving a legibility to the underlying relations.

This is why ATLAS shows the game to which numerous artists have given themselves, this “infinite natural history” (according to Paul Klee) or that “atlas of the impossible” (according to Michel Foucault regarding the disconcerting erudition of Jorge Luis Borges). We can discover, then, in what sense contemporary artists are “scholars” or inventors of a special genre: they gather the scattered pieces of the world as would a child or a rag-and- bone man – two figures to whom Walter Benjamin compared the authentic materialist scholar. They bring together things outside of normal classifications, and glean from these affinities a new kind of knowledge which opens our eyes to certain unperceived aspects of our world and to the unconscious of our vision.

Piecing together the order of places

To make an atlas is to reconfigure space, to redistribute it, in short, to redirect it: to dismantle it where we thought it was continuous; to reunite it where we thought there were boundaries. Arthur Rimbaud once cut up a geographical atlas in order to record, on the pieces obtained, his personal iconography. Later, Marcel Broodthaers, On Kawara and Guy Debord invented several forms of alternative geographies. Warburg, for his part, had already understood that every image – every production of culture in general – is the crossing of numerous migrations: it is to Baghdad, for example, that he went to find unperceived meanings of certain frescoes of the Italian Renaissance.

There are many contemporary artists who are not content to rely solely on the landscape to tell us about a country: this is why they bring together, on the same surface – or plate of an atlas – different ways of representing space. It is a way of seeing the world and of going through it according to heterogeneous viewpoints combined with one another, as we see in the works of Alighiero e Boetti, Dennis Oppenheim or, more generally, in the way that the urban metropolis was envisaged, from Man with a Movie Camera by Dziga Vertov to recent installations by Harun Farocki.

Piecing together the order of time

If the atlas appears as an incessant work of re-composing of the world, it is first of all because the world itself does not cease to undergo decomposition upon decomposition. Bertolt Brecht said of the “dismantling of the world” that it is “the true subject of art” (it should be enough, to understand this, to think of Guernica). Warburg, by contrast, saw cultural history as a genuine field of conflict, a “psychomachia”, a “titanomachia”, and a perpetual “tragedy”. We could say that many artists adopted this point of view by reacting against the historical tragedies of their time with a work in which montage, once again, played the central role: we can think of the photomontages of John Heartfield in the 1930’s, or more recently, Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma, and the work of artists like Walid Raad or Pascal Convert.

It is therefore time itself which becomes visible in the montage of images. It is up to everyone – artist or scholar, thinker or poet – to make such a visibility into a power to see the times: a resource for observing history, for undertaking its archaeology and its political critique, for “dismantling” it in order to imagine alternative models.

Georges Didi-Huberman