Otto Freundlich

Cosmic Communism

18 Feb - 14 May 2017

Installation view "Otto Freundlich: Cosmic Communism", Museum Ludwig Köln, Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Cologne / Britta Schlier

Installation view "Otto Freundlich: Cosmic Communism", Museum Ludwig Köln, Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Cologne / Britta Schlier

Installation view "Otto Freundlich: Cosmic Communism", Museum Ludwig Köln, Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Cologne / Britta Schlier

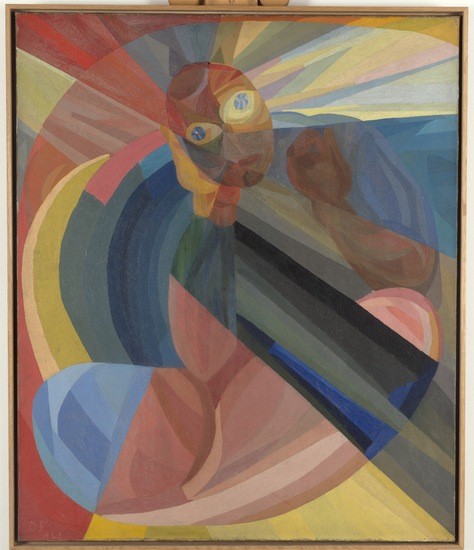

Otto Freundlich, The Mother, 1921, oil on canvas (cotton), Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, Photo: Kai-Annet Becker

Otto Freundlich, Rosette II (La Rosace II), 1941, gouache on cardboard, Musées de Pontoise, Photo: Donation Freundlich, Musées de Pontoise

Otto Freundlich, Composition, 1930, oil on canvas, Musées de Pontoise, Photo: Donation Freundlich, Musées de Pontoise

OTTO FREUNDLICH

Cosmic Communism

18 February – 14 May 2017

Curator: Julia Friedrich

He is one of the most original abstract artists of the twentieth century. Nearly forty years after the large retrospective, the Museum Ludwig will now present the oeuvre of Otto Freundlich (1878–1943). With around eighty objects, the exhibition traces the work, thought, and life of an artist who produced not only paintings and sculptures but also stained-glass windows and mosaics, and who in a searching reflection on the leading art movements of his time found his own path to abstraction—before being marginalized by the Nazis, denounced as “degenerate,” and ultimately murdered as a Jew.

This discrimination and eradication of both Freundlich and his work have marked the artist’s reception to this day. Many of his works were destroyed in Germany under National Socialism. His Großer Kopf (Large Head), which the Nazis reproduced on the cover of their guide to the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition in 1938, remains his most famous work even today. This retrospective demonstrates that the Nazis not only falsified the title of the work (they gave it the title “The New Man” by which it is still known today), but even the sculpture itself: at least at one venue on the Degenerate Art touring exhibition they presented a crude copy in place of the original. The Museum Ludwig is now providing visitors a chance to encounter Freundlich’s entire oeuvre and places it at the center of contemporaneous art-historical developments. It begins with the heads he drew and sculpted around 1910 and features his little-known applied artworks alongside his sculptures, paintings, and gouaches. Moreover, it offers insights into Freundlich’s writings, in which he positioned his work in its social and artistic context.

Freundlich, who lived in Paris from 1924 onward, was friends with many of the leading artists of his time. An appeal to the French state to buy one of his works in 1938 was signed by Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Alfred Döblin, Wassily Kandinsky, Pablo Picasso, and many others. His singular development was characterized by his initial close engagement with the applied arts. Through carpets, mosaics, and painted glass he continued the medieval tradition of the guilds, which he linked with a collective art of the future. In the luminous flat surfaces of old church windows, he saw a way to overcome the limitations of a plastic art conceived of in terms of the contours of the objects.

With his own applied artworks and above all his abstract pieces, Freundlich took this approach even further. For him, abstraction expressed a radical renewal that went far beyond art. For instance, the curved patches of color in his paintings reflect the concept of space in Einsteinian physics, with which he was familiar from an early age. Still, overcoming representationalism also had a social dimension for him. As he saw it, every form of material perception was permeated with possessiveness and thus outdated: “The object as the antithesis to the individual will disappear, and with it the state of one person being an object for another.” He always viewed the harmony of the colors in his paintings in the context of the greater whole. The Communism, for which he fought, sought to abolish all boundaries “between the world and the cosmos, between human beings, between mine and yours, between all things that we see.”

The retrospective brings together numerous loans. One of the finest objects—and a centerpiece of the exhibition—comes from Cologne: the impressive mosaic Geburt des Menschen (Birth of Man, 1919), which miraculously survived National Socialism and World War II hidden away in a shed. In 1957 the City of Cologne installed it in the newly constructed opera house. Yet although the piece was always accessible to the public, it gradually drifted into obscurity. Now it will be on view at the Museum Ludwig as a major work by the artist, and for the first time in the context of his entire oeuvre. The exhibition was conceived by Julia Friedrich at the Museum Ludwig. After Cologne, it will be presented from June 10 to September 10, 2017, at the Kunstmuseum Basel. It was organized in cooperation with the Musée Tavet-Delacour in Pontoise, which holds Freundlich’s estate.

The exhibition is under the patronage of the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media Monika Grütters. It has received generous support from the Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne, the Kulturstiftung der Länder, the Landschaftsverband Rheinland, and the Freunde des Wallraf-Richartz-Museum und des Museum Ludwig e.V.

Cosmic Communism

18 February – 14 May 2017

Curator: Julia Friedrich

He is one of the most original abstract artists of the twentieth century. Nearly forty years after the large retrospective, the Museum Ludwig will now present the oeuvre of Otto Freundlich (1878–1943). With around eighty objects, the exhibition traces the work, thought, and life of an artist who produced not only paintings and sculptures but also stained-glass windows and mosaics, and who in a searching reflection on the leading art movements of his time found his own path to abstraction—before being marginalized by the Nazis, denounced as “degenerate,” and ultimately murdered as a Jew.

This discrimination and eradication of both Freundlich and his work have marked the artist’s reception to this day. Many of his works were destroyed in Germany under National Socialism. His Großer Kopf (Large Head), which the Nazis reproduced on the cover of their guide to the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition in 1938, remains his most famous work even today. This retrospective demonstrates that the Nazis not only falsified the title of the work (they gave it the title “The New Man” by which it is still known today), but even the sculpture itself: at least at one venue on the Degenerate Art touring exhibition they presented a crude copy in place of the original. The Museum Ludwig is now providing visitors a chance to encounter Freundlich’s entire oeuvre and places it at the center of contemporaneous art-historical developments. It begins with the heads he drew and sculpted around 1910 and features his little-known applied artworks alongside his sculptures, paintings, and gouaches. Moreover, it offers insights into Freundlich’s writings, in which he positioned his work in its social and artistic context.

Freundlich, who lived in Paris from 1924 onward, was friends with many of the leading artists of his time. An appeal to the French state to buy one of his works in 1938 was signed by Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Alfred Döblin, Wassily Kandinsky, Pablo Picasso, and many others. His singular development was characterized by his initial close engagement with the applied arts. Through carpets, mosaics, and painted glass he continued the medieval tradition of the guilds, which he linked with a collective art of the future. In the luminous flat surfaces of old church windows, he saw a way to overcome the limitations of a plastic art conceived of in terms of the contours of the objects.

With his own applied artworks and above all his abstract pieces, Freundlich took this approach even further. For him, abstraction expressed a radical renewal that went far beyond art. For instance, the curved patches of color in his paintings reflect the concept of space in Einsteinian physics, with which he was familiar from an early age. Still, overcoming representationalism also had a social dimension for him. As he saw it, every form of material perception was permeated with possessiveness and thus outdated: “The object as the antithesis to the individual will disappear, and with it the state of one person being an object for another.” He always viewed the harmony of the colors in his paintings in the context of the greater whole. The Communism, for which he fought, sought to abolish all boundaries “between the world and the cosmos, between human beings, between mine and yours, between all things that we see.”

The retrospective brings together numerous loans. One of the finest objects—and a centerpiece of the exhibition—comes from Cologne: the impressive mosaic Geburt des Menschen (Birth of Man, 1919), which miraculously survived National Socialism and World War II hidden away in a shed. In 1957 the City of Cologne installed it in the newly constructed opera house. Yet although the piece was always accessible to the public, it gradually drifted into obscurity. Now it will be on view at the Museum Ludwig as a major work by the artist, and for the first time in the context of his entire oeuvre. The exhibition was conceived by Julia Friedrich at the Museum Ludwig. After Cologne, it will be presented from June 10 to September 10, 2017, at the Kunstmuseum Basel. It was organized in cooperation with the Musée Tavet-Delacour in Pontoise, which holds Freundlich’s estate.

The exhibition is under the patronage of the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media Monika Grütters. It has received generous support from the Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne, the Kulturstiftung der Länder, the Landschaftsverband Rheinland, and the Freunde des Wallraf-Richartz-Museum und des Museum Ludwig e.V.