Fresh Window. The Art of Display & Display of Art

04 Dec 2024 - 11 May 2025

For decades, there have been close links between the histories of art and shop window display. Besides Jean Tinguely, many other artists have designed pioneering window displays. Conversely, window displays frequently feature as a motif in artworks or serve as a stage for performances and actions. The exhibition explores this eventful relationship from its beginnings to the present day, while >> artistic interventions in shop windows in Basel extend the show into public space.

Art and shop windows may seem like unusual partners, but if one takes a look at their shared history of shop window displays, one finds a long tradition. In the late nineteenth century, when window displays developed into a central element of modern consumer culture, people soon began to think about the potential for presenting commodities in aesthetic ways. With surprising and creative displays, such windows were the store’s street-facing calling card, inviting people to stop and look, around the clock, as well as informing passersby about special offers, always with the aim of generating sales.

Artists soon began exploring this new phenomenon. Following his absurd take on the window’s functions and meanings in his 1920 work Fresh Widow, Marcel Duchamp designed his first shop window display in 1945 for the launch of a book by André Breton in New York. By then, Jean Tinguely was already working as a professional window dresser in Basel. Having begun his apprenticeship at the Globus department store in 1941, he was fired in 1943 for lack of discipline. He completed his training in 1944 with the freelance window dresser Joos Hutter, who encouraged him to attend Basel’s school of applied arts. Often made out of wire, his window designs – for clients including the opticians Ramstein Iberg Co., the bookstore Tanner, and the furniture store Wohnbedarf Jehle – anticipated the signature style of his later artworks.

In 1950s New York, too, artists supplemented their income with regular jobs in this field. An important role here was played by Gene Moore, who fostered the talent of young, unknown artists in his position as art director for the department store Bonwit Teller and the jeweller Tiffany & Co., where he would select works by Sari Dienes or Susan Weil for window displays, or commission elaborate designs from Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns or Andy Warhol before they became established in the art world. Some of these shop window designs are documented in the exhibition in the form of photographs, while others have been faithfully reconstructed, allowing them to be rediscovered some 70 years later.

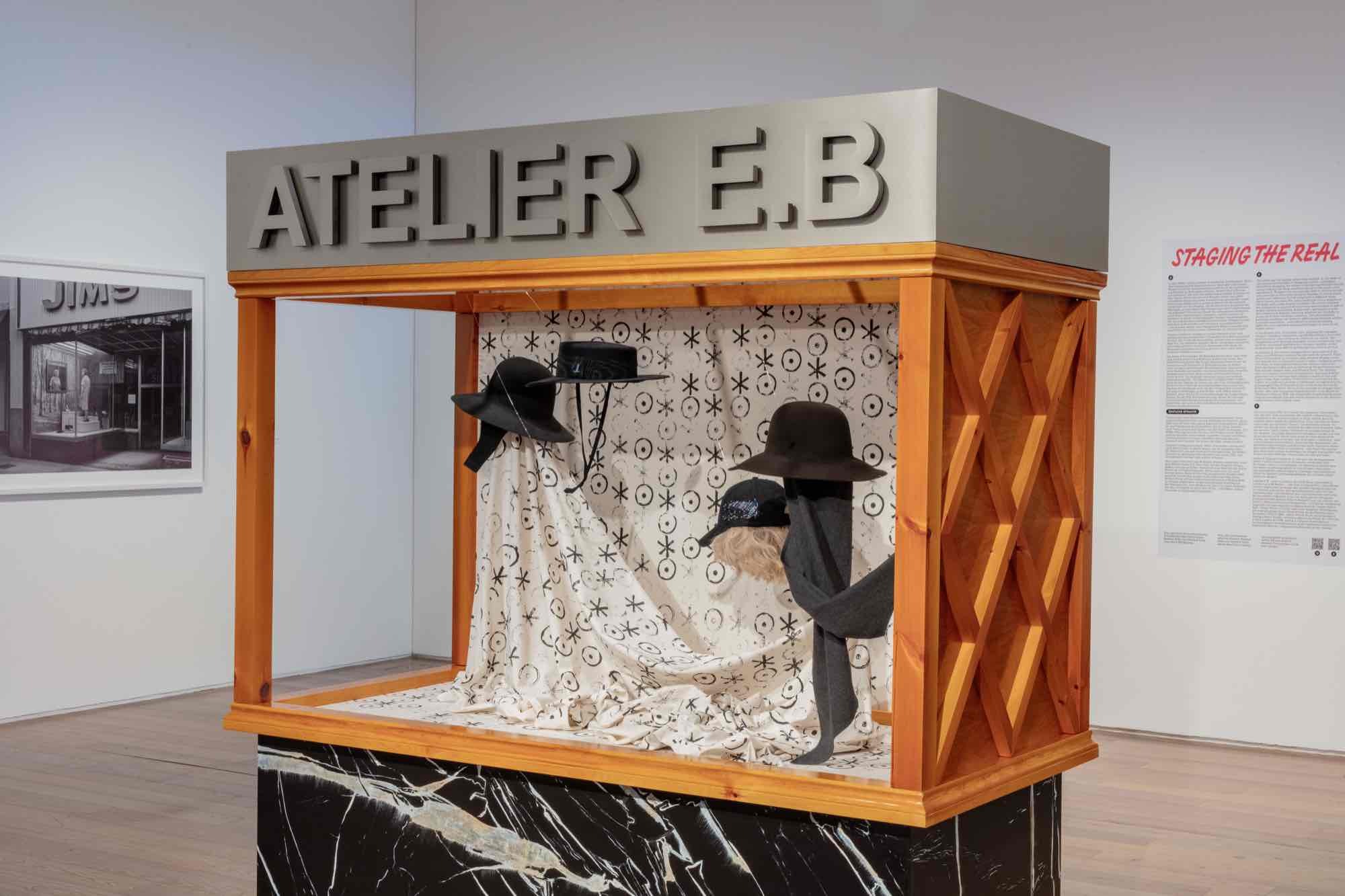

Conversely, such displays featured as motifs in many paintings, installations, sculptures, video works and series of photographs – works that deal with the qualities and associative potential inherent in shop windows. In the 1960s and ‘70s, Richard Estes, Peter Blake and Ion Grigorescu addressed the colourful, exuberant world of capitalism. The seductive function of window displays was highlighted in Lèche Vitrines (2020), a performance by Martina Morger who acted out the title (French for “window shopping”) by licking shop windows in Paris. With the veiled windows of his Store Fronts (1964–68), Christo played on the aspect of voyeurism and on the sculptural properties of shop displays. The scenographic mastery of traditional window dressing is referred to in the Street Vitrines (2020) by Atelier E.B (Beca Lipscombe & Lucy McKenzie) and in Anna Franceschini’s video work Did you know you have a broken glass in the window? (2020).

As highly visible spaces in prominent locations, shop windows also proved interesting for performance artists. With the aim of reaching the largest, most diverse audience possible, social and political issues have often been addressed on this stage. In October 1969, Tinguely’s Rotozaza III was activated in the window of the Bern department store Loeb: by smashing crockery in front of a crowd of onlookers, it playfully criticized the western world’s excessive consumerism. Vlasta Delimar and María Teresa Hincapié used shop windows to draw attention to conventional role models for women. In her 1976 performance Role Exchange, Marina Abramović swapped workplaces with a prostitute in Amsterdam and spent two hours sitting in the window of a brothel. In this way, she questioned not only the value attributed to different activities, but also the moral connotations of the display window.

In 1976, Lynn Hershman Leeson used the windows at the Bonwit Teller department store for a portrait of New York City in the form of a multimedia installation. Rather than presenting objects for sale, the sequence of narratively interlinked scenes offered food for thought. In 1980, Sherrie Rabinowitz and Kit Galloway used cutting-edge technology to allow people walking past a shop window in New York to communicate with people walking around Los Angeles via a kind of video telephony. This work, Hole in Space, is a wonderful illustration of the roles a shop window can play: a place for interactions, discussions and encounters.

The exhibition is curated by Adrian Dannatt, freelance curator and art critic, Tabea Panizzi, curator at Museum Tinguely, and Andres Pardey, vice director at Museum Tinguely. Assistant: Melanie Keller.

Art and shop windows may seem like unusual partners, but if one takes a look at their shared history of shop window displays, one finds a long tradition. In the late nineteenth century, when window displays developed into a central element of modern consumer culture, people soon began to think about the potential for presenting commodities in aesthetic ways. With surprising and creative displays, such windows were the store’s street-facing calling card, inviting people to stop and look, around the clock, as well as informing passersby about special offers, always with the aim of generating sales.

Artists soon began exploring this new phenomenon. Following his absurd take on the window’s functions and meanings in his 1920 work Fresh Widow, Marcel Duchamp designed his first shop window display in 1945 for the launch of a book by André Breton in New York. By then, Jean Tinguely was already working as a professional window dresser in Basel. Having begun his apprenticeship at the Globus department store in 1941, he was fired in 1943 for lack of discipline. He completed his training in 1944 with the freelance window dresser Joos Hutter, who encouraged him to attend Basel’s school of applied arts. Often made out of wire, his window designs – for clients including the opticians Ramstein Iberg Co., the bookstore Tanner, and the furniture store Wohnbedarf Jehle – anticipated the signature style of his later artworks.

In 1950s New York, too, artists supplemented their income with regular jobs in this field. An important role here was played by Gene Moore, who fostered the talent of young, unknown artists in his position as art director for the department store Bonwit Teller and the jeweller Tiffany & Co., where he would select works by Sari Dienes or Susan Weil for window displays, or commission elaborate designs from Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns or Andy Warhol before they became established in the art world. Some of these shop window designs are documented in the exhibition in the form of photographs, while others have been faithfully reconstructed, allowing them to be rediscovered some 70 years later.

Conversely, such displays featured as motifs in many paintings, installations, sculptures, video works and series of photographs – works that deal with the qualities and associative potential inherent in shop windows. In the 1960s and ‘70s, Richard Estes, Peter Blake and Ion Grigorescu addressed the colourful, exuberant world of capitalism. The seductive function of window displays was highlighted in Lèche Vitrines (2020), a performance by Martina Morger who acted out the title (French for “window shopping”) by licking shop windows in Paris. With the veiled windows of his Store Fronts (1964–68), Christo played on the aspect of voyeurism and on the sculptural properties of shop displays. The scenographic mastery of traditional window dressing is referred to in the Street Vitrines (2020) by Atelier E.B (Beca Lipscombe & Lucy McKenzie) and in Anna Franceschini’s video work Did you know you have a broken glass in the window? (2020).

As highly visible spaces in prominent locations, shop windows also proved interesting for performance artists. With the aim of reaching the largest, most diverse audience possible, social and political issues have often been addressed on this stage. In October 1969, Tinguely’s Rotozaza III was activated in the window of the Bern department store Loeb: by smashing crockery in front of a crowd of onlookers, it playfully criticized the western world’s excessive consumerism. Vlasta Delimar and María Teresa Hincapié used shop windows to draw attention to conventional role models for women. In her 1976 performance Role Exchange, Marina Abramović swapped workplaces with a prostitute in Amsterdam and spent two hours sitting in the window of a brothel. In this way, she questioned not only the value attributed to different activities, but also the moral connotations of the display window.

In 1976, Lynn Hershman Leeson used the windows at the Bonwit Teller department store for a portrait of New York City in the form of a multimedia installation. Rather than presenting objects for sale, the sequence of narratively interlinked scenes offered food for thought. In 1980, Sherrie Rabinowitz and Kit Galloway used cutting-edge technology to allow people walking past a shop window in New York to communicate with people walking around Los Angeles via a kind of video telephony. This work, Hole in Space, is a wonderful illustration of the roles a shop window can play: a place for interactions, discussions and encounters.

The exhibition is curated by Adrian Dannatt, freelance curator and art critic, Tabea Panizzi, curator at Museum Tinguely, and Andres Pardey, vice director at Museum Tinguely. Assistant: Melanie Keller.