Pavel Pepperstein

22 Apr - 25 Jun 2016

© Pavel Pepperstein

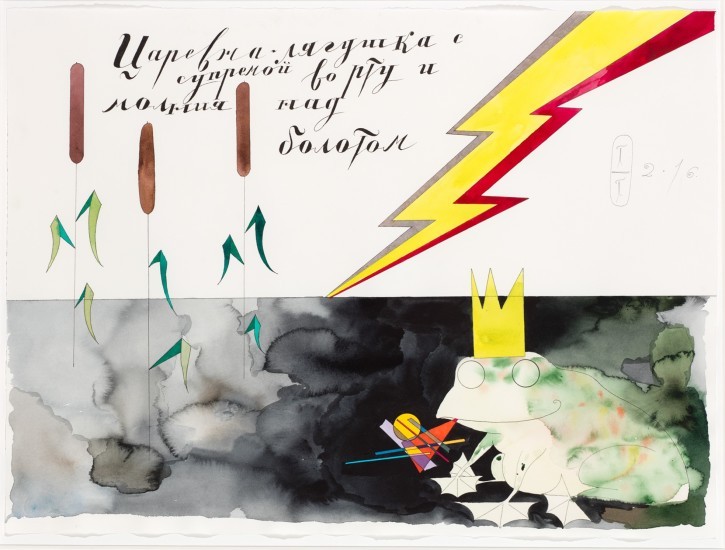

Tsarevna-lyagushka with suprema in her mouth from the series MIRACLES IN THE SWAMP, 2016

Tsarevna-lyagushka with suprema in her mouth from the series MIRACLES IN THE SWAMP, 2016

PAVEL PEPPERSTEIN

Miracles In The Swamp

22 April - 25 June 2016

It is Kafka’s hate towards history that Walter Benjamin variously discussed in his book «On Kafka». Indeed, distaste in history (historiophobia) is an interesting phenomenon which deserves closer scrutiny. Today this subject is of serious matter given by the fact that “the End of History” manifested by postmodernist ideology did not come off – anyway, it didn’t happen in the sense intended by postmodernists.

Postmodernist Utopia regarded “the End of History” as the triumph of museum, of museumification principle. In recent years we observe the omnipresent death-blow of that principle –barbarian destruction of ancient heritage that miraculously survived to our unthankful days. This destruction is carried out in different spheres: one has only to compare ISIS or Taliban performance with the actions of art-vandals that, with delight, rough in maggots and other attributes of decay to canvases of Bruegel (Chapman brothers), shiver vintage Chinese vases etc. Thus, history continues in rude and coarse forms that seemed to have been gone forever. Ironically, it is historiophobia that guarantees the continuation of history. If the past still stimulates aggressive actions of this kind – then it is alive.

History goes on; then there is a place for Kafka’s feelings. Nevertheless the writer of Prague suggested that there is power, able to confront history. Kafka defined this force as a “swamp” (or “dibloto” in Yiddish). A swamp is counter-historical by nature; all the challenging projects of reinvention, colonizing and emancipatory impulses – roughly speaking, everything sinks and sticks within it. In everyday and political language this word is generally used in negative sense, but Kafka, a profound post-judaical mystic, is absolutely right: a swamp is our only hope, as the events of our days again and again show us that “there is nothing more disgusting than history” (in words). Prague hypochondriac’s wisdom is in a state of radical opposition to every perspective discourse – for example, discourse of suprematism. That is why, if we seek for a pair of opponents, it will be Malevich and Kafka. The exhibition makes up a phantom dialogue, or скорее, a dispute between these uncompromising concerns. There will be supremas, architects, political figures, managers and other agents of active abstraction behind the back of Malevich. Behind the back of Kafka stand the flowering of swamp lotus (and swamp logos), fagots, gollums, magister Yoda, swamp fairies, agrarians, books, mushrooms, museum collections and so on. Who wins?

In fact, this whole gladiator fight is fictional. There is more in common between Malevich and Kafka than it seems at a first glance. A swamp is a territory (including territory of thought) where the surface and the depth change places. In Kurt Vonnegut’s novel “Cat’s Cradle” high military executives set a task for scientists – to invent a universal remedy for swamps in which the battalions are sticking within. A researcher called Honicker invents the sought-for substance – so-called «ice-nine» that momentarily freezes any liquid viscidity. In the end «ice-nine» freezes the Earth: life itself happens to be a swamp, and anti-swamp remedy automatically destroys life. «Ice-nine» is a kind of hyper-suprema, and Honicker somehow resembles Malevich or British colonists in India who plumed themselves with the anti-swamp program. But still, while history is no more than a swamp phantom, its swampy essence wouldn’t undergo any changes.

Pavel Pepperstein 29.03.2016

Miracles In The Swamp

22 April - 25 June 2016

It is Kafka’s hate towards history that Walter Benjamin variously discussed in his book «On Kafka». Indeed, distaste in history (historiophobia) is an interesting phenomenon which deserves closer scrutiny. Today this subject is of serious matter given by the fact that “the End of History” manifested by postmodernist ideology did not come off – anyway, it didn’t happen in the sense intended by postmodernists.

Postmodernist Utopia regarded “the End of History” as the triumph of museum, of museumification principle. In recent years we observe the omnipresent death-blow of that principle –barbarian destruction of ancient heritage that miraculously survived to our unthankful days. This destruction is carried out in different spheres: one has only to compare ISIS or Taliban performance with the actions of art-vandals that, with delight, rough in maggots and other attributes of decay to canvases of Bruegel (Chapman brothers), shiver vintage Chinese vases etc. Thus, history continues in rude and coarse forms that seemed to have been gone forever. Ironically, it is historiophobia that guarantees the continuation of history. If the past still stimulates aggressive actions of this kind – then it is alive.

History goes on; then there is a place for Kafka’s feelings. Nevertheless the writer of Prague suggested that there is power, able to confront history. Kafka defined this force as a “swamp” (or “dibloto” in Yiddish). A swamp is counter-historical by nature; all the challenging projects of reinvention, colonizing and emancipatory impulses – roughly speaking, everything sinks and sticks within it. In everyday and political language this word is generally used in negative sense, but Kafka, a profound post-judaical mystic, is absolutely right: a swamp is our only hope, as the events of our days again and again show us that “there is nothing more disgusting than history” (in words). Prague hypochondriac’s wisdom is in a state of radical opposition to every perspective discourse – for example, discourse of suprematism. That is why, if we seek for a pair of opponents, it will be Malevich and Kafka. The exhibition makes up a phantom dialogue, or скорее, a dispute between these uncompromising concerns. There will be supremas, architects, political figures, managers and other agents of active abstraction behind the back of Malevich. Behind the back of Kafka stand the flowering of swamp lotus (and swamp logos), fagots, gollums, magister Yoda, swamp fairies, agrarians, books, mushrooms, museum collections and so on. Who wins?

In fact, this whole gladiator fight is fictional. There is more in common between Malevich and Kafka than it seems at a first glance. A swamp is a territory (including territory of thought) where the surface and the depth change places. In Kurt Vonnegut’s novel “Cat’s Cradle” high military executives set a task for scientists – to invent a universal remedy for swamps in which the battalions are sticking within. A researcher called Honicker invents the sought-for substance – so-called «ice-nine» that momentarily freezes any liquid viscidity. In the end «ice-nine» freezes the Earth: life itself happens to be a swamp, and anti-swamp remedy automatically destroys life. «Ice-nine» is a kind of hyper-suprema, and Honicker somehow resembles Malevich or British colonists in India who plumed themselves with the anti-swamp program. But still, while history is no more than a swamp phantom, its swampy essence wouldn’t undergo any changes.

Pavel Pepperstein 29.03.2016