Anna Rettl

Laocoön Loop

26 Aug - 29 Oct 2023

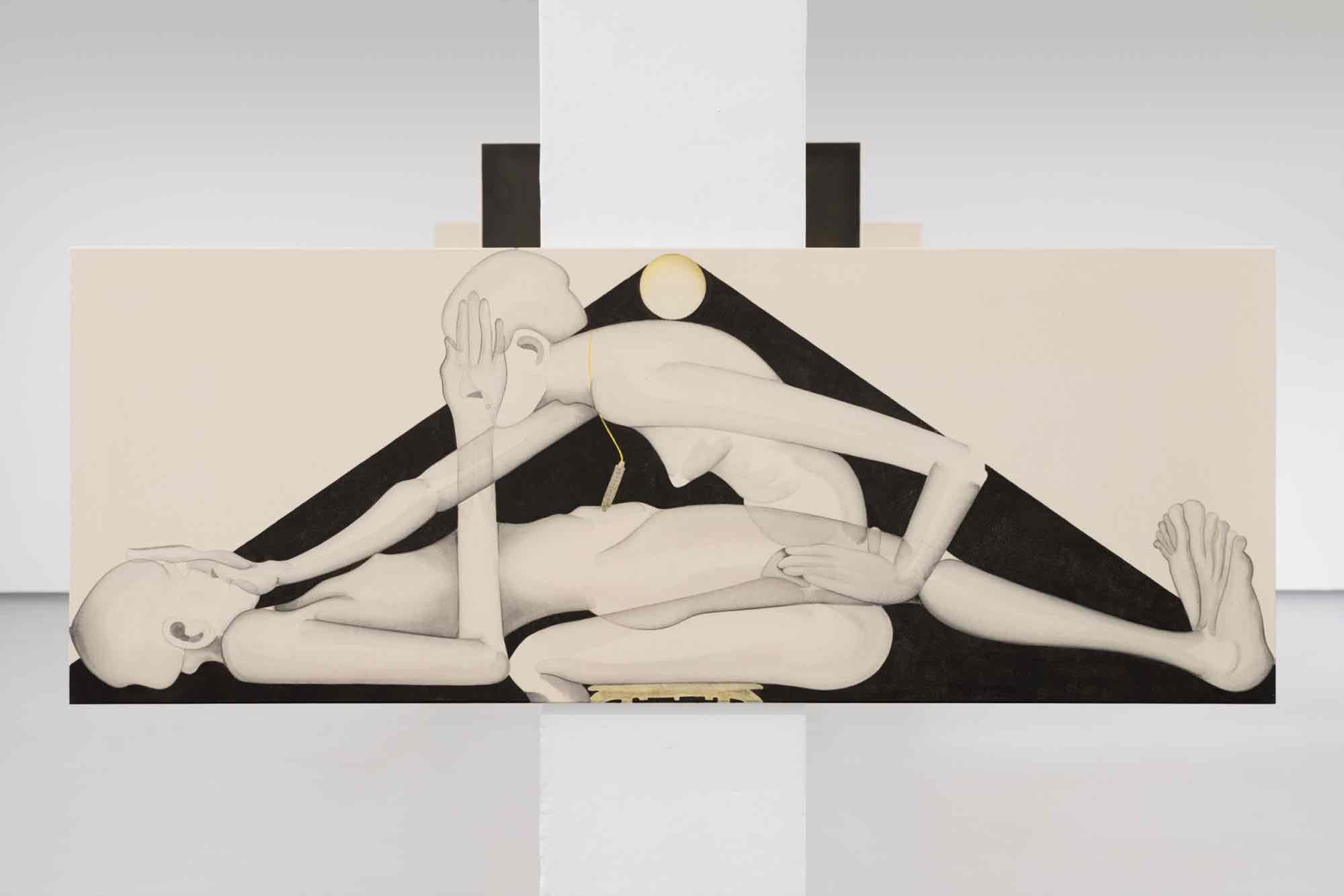

Anna Rettl: The Best Doctor, after Alfred Kubin, 2023. Watercolor and ink on cotton canvas primed with rabbit skin clue, 70 x 185 cm. Photo: David Stjernholm

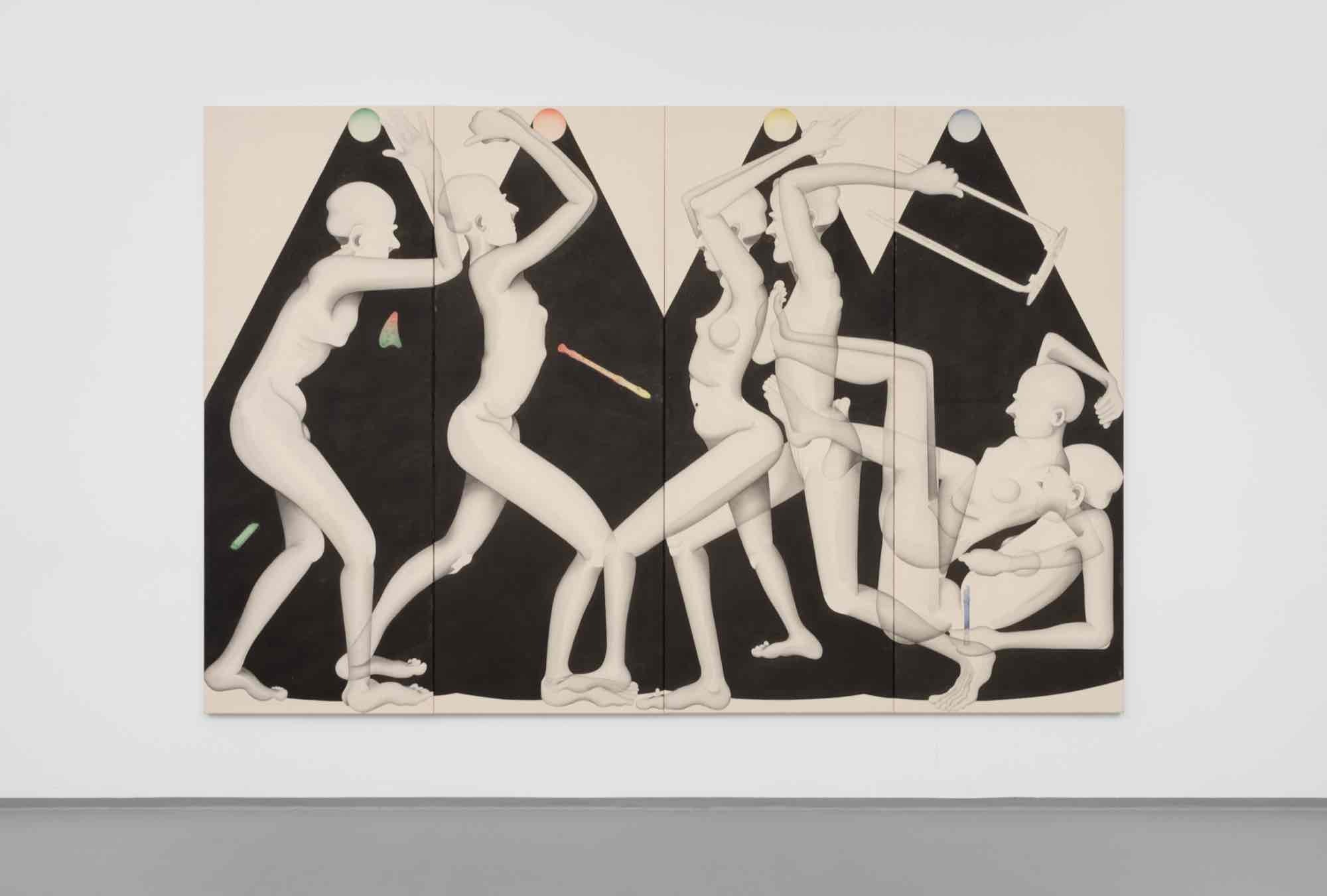

Anna Rettl: The Brawl, after Fortunato Depero, 2023. Watercolor and ink on cotton canvas primed with acrylic binder, 185 x 280 cm. Photo: David Stjernholm

Anna Rettl: Man, after Alfred Kubin, 2023. Installation view, O—Overgaden. Watercolor and ink on linen, canvas primed with gesso, 185 x 140 cm. Photo: David Stjernholm

The work of the young painter Anna Rettl is deeply rooted in art history—think human figures adorned in attire indicating social rank by masters such as Hieronymus Bosch, Eugène Delacroix, and Peter Paul Rubens. Specializing in large-scale watercolors on canvas, Rettl expands existing characters from the annals of painting while stripping their bodies bare. Removing all markers or clothing, as if depicting the naked truth of an era, Rettl’s works come close to anatomical studies inherent to a certain time and ideology.

For O—Overgaden, Rettl has produced a new series of watercolors referencing early 20th-century modernist paintings, created during the rise of fascism in central Europe. Influences are obscure waves of early abstraction, Viennese modernism, and the technological, machinic fascination associated with Italian futurism in Rettl’s region of origin: the crux between Austria, Italy, and Slovenia. In her new series, lean and distorted bodies in states of agitation stretch to combat a new industrial, capitalist, and war-ridden world, hanging as a cabinet of corpses crawling off the wall, across the exhibition spaces.

Formally, Rettl employs two different types of canvas: cheap cotton and the more expensive, darker linen while working with three different primers—ancient “rabbit skin glue”, the more modern “white gesso”, and the recently fashionable “acrylic primer”. Hence, despite the series’ coherent appearance, the experiment of creating oversized watercolors is risk-taking, stretching the medium far beyond its typical use on paper. Each piece requires repeated layering to produce the saturated, dense, but still vital, fresh, ephemeral watercolor look of the figures.

In terms of motifs, an army of stereotypical bodies repeat. Hunched backs, kicking legs, tight fists, giant feet, crooked noses, exaggerated skulls, praying hands, contoured, shadowy skeletal limbs, and bulky thin bellies are placed on symmetrical black ink backgrounds. Taking a cue from Adolescence by Elena Luksch-Makowsky (Rettl’s remake hangs on the back space’s left wall), the figures are fluid, many androgynously undefined on the threshold of adulthood—in part referencing the artist’s own sister as model. Meanwhile other eclectic sources for the motifs span Alfred Kubin’s nightmarish visions (referenced in the show’s first diptych) and other little-known painters including futurist Gino Severini and Austrian Albin Egger-Lienz’s painting of soldiers The Nameless 1914, here repeated with clarinets instead of munitions.

Beyond the human depictions, rubbings or “frottages” of brass instruments—the military-type horns of marching bands—occur in Rettl’s series, sometimes as substitutes for weaponry in the original paintings, as just exemplified. In Rettl’s words, these constitute “Ordnungselemente”: systematic elements creating rhythmic recognition throughout. A rubbing of an IKEA stool also repeats. This motif directly quotes a photograph of a well-used work chair in the artist’s studio, and thus intermixes Rettl’s ongoing investigation into a particular time period, its physical compositions, and historical painting techniques with contemporary life, not least her own work and family (employed as models). This serves as a reminder of how the militant disciplining of the individual human body stemming from the early 20th-century is far from ancient history but rather a persistent, potentially even growing, strenuous condition. As with the antique sculpture Laocoön, famously rediscovered in the renaissance, our darkest history is looping, and deeply inscribed in contemporary culture, as alluded to in the title: Laocoön Loop.

For O—Overgaden, Rettl has produced a new series of watercolors referencing early 20th-century modernist paintings, created during the rise of fascism in central Europe. Influences are obscure waves of early abstraction, Viennese modernism, and the technological, machinic fascination associated with Italian futurism in Rettl’s region of origin: the crux between Austria, Italy, and Slovenia. In her new series, lean and distorted bodies in states of agitation stretch to combat a new industrial, capitalist, and war-ridden world, hanging as a cabinet of corpses crawling off the wall, across the exhibition spaces.

Formally, Rettl employs two different types of canvas: cheap cotton and the more expensive, darker linen while working with three different primers—ancient “rabbit skin glue”, the more modern “white gesso”, and the recently fashionable “acrylic primer”. Hence, despite the series’ coherent appearance, the experiment of creating oversized watercolors is risk-taking, stretching the medium far beyond its typical use on paper. Each piece requires repeated layering to produce the saturated, dense, but still vital, fresh, ephemeral watercolor look of the figures.

In terms of motifs, an army of stereotypical bodies repeat. Hunched backs, kicking legs, tight fists, giant feet, crooked noses, exaggerated skulls, praying hands, contoured, shadowy skeletal limbs, and bulky thin bellies are placed on symmetrical black ink backgrounds. Taking a cue from Adolescence by Elena Luksch-Makowsky (Rettl’s remake hangs on the back space’s left wall), the figures are fluid, many androgynously undefined on the threshold of adulthood—in part referencing the artist’s own sister as model. Meanwhile other eclectic sources for the motifs span Alfred Kubin’s nightmarish visions (referenced in the show’s first diptych) and other little-known painters including futurist Gino Severini and Austrian Albin Egger-Lienz’s painting of soldiers The Nameless 1914, here repeated with clarinets instead of munitions.

Beyond the human depictions, rubbings or “frottages” of brass instruments—the military-type horns of marching bands—occur in Rettl’s series, sometimes as substitutes for weaponry in the original paintings, as just exemplified. In Rettl’s words, these constitute “Ordnungselemente”: systematic elements creating rhythmic recognition throughout. A rubbing of an IKEA stool also repeats. This motif directly quotes a photograph of a well-used work chair in the artist’s studio, and thus intermixes Rettl’s ongoing investigation into a particular time period, its physical compositions, and historical painting techniques with contemporary life, not least her own work and family (employed as models). This serves as a reminder of how the militant disciplining of the individual human body stemming from the early 20th-century is far from ancient history but rather a persistent, potentially even growing, strenuous condition. As with the antique sculpture Laocoön, famously rediscovered in the renaissance, our darkest history is looping, and deeply inscribed in contemporary culture, as alluded to in the title: Laocoön Loop.