Melanie Kitti

Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue

27 May - 06 Aug 2023

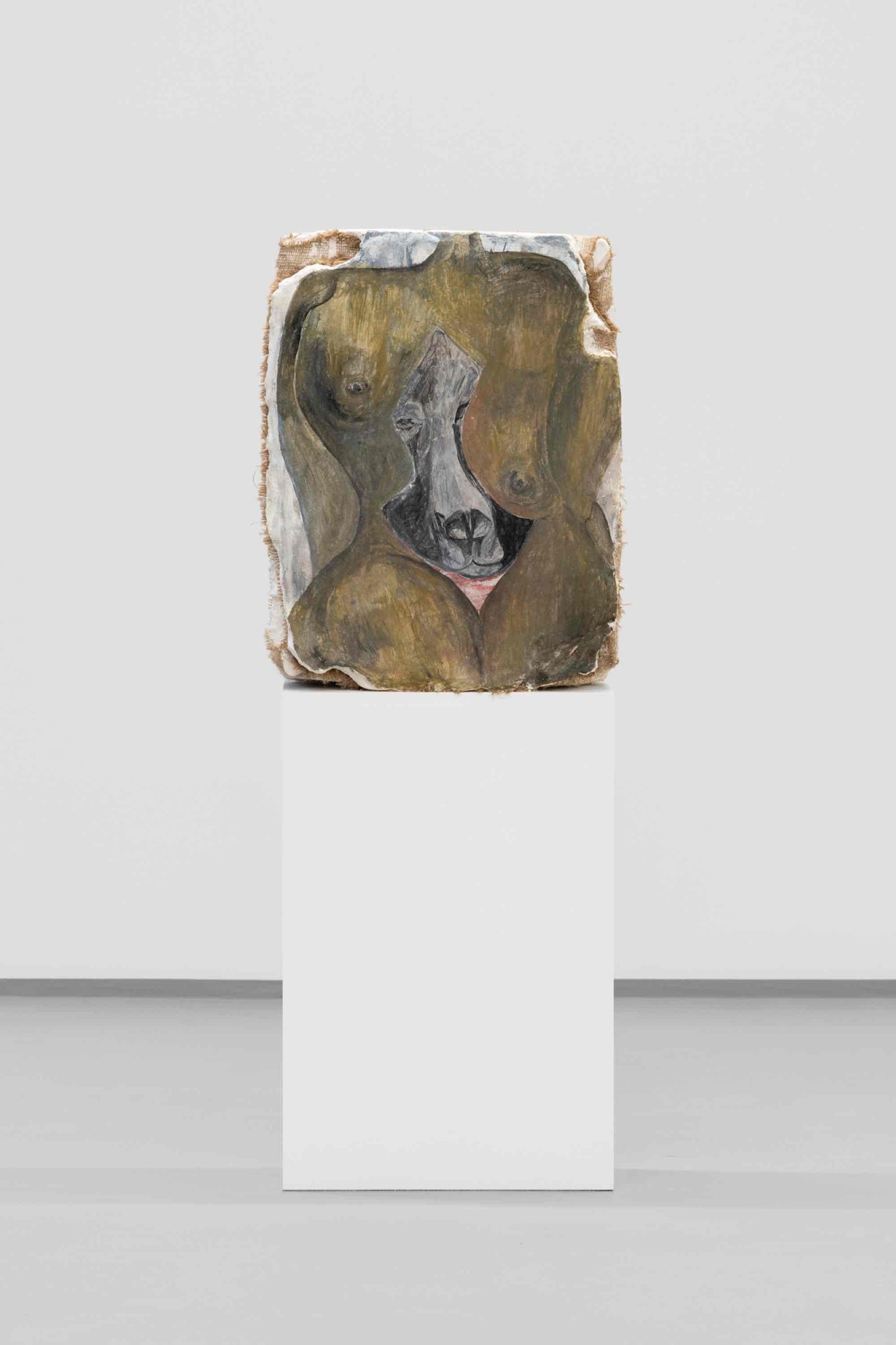

Melanie Kitti: Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue, installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Melanie Kitti: Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue, installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Melanie Kitti: Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue, installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Melanie Kitti: Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue, installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Melanie Kitti: Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue, installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Melanie Kitti: Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue, installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Melanie Kitti: Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue, installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Melanie Kitti: Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue, installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Melanie Kitti: Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue, installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

The young Swedish artist Melanie Kitti’s writing and visual arts practice stems from a place of disruption, fragmentation, and discontinuity. Her acclaimed literary debut, Halvt urne, halvt gral (Half Urn, Half Grail, Gyldendal, 2022), collects succinct and fleeting notes on a family—and consequently a mental state—about to dissolve. Her painterly practice employs DIY fresco techniques on bulks created from, for instance, plaster. Using materials impossible to preserve, she creates a frailty always at risk of imploding.

For her grand solo show at O—Overgaden, Kitti presents two new work series. One consists of frescoes painted on clunky sculptural surfaces: lumpy plaster molded with hessian cloth, the traditional method for creating portrait busts. The other is a series of wall-hung painted plaster surfaces that zoom in on the upper human torso, throat, and neck, the place from which we try to utter stuff, but also the place where anxiety and depression can form blockages and arrest or (self)censor the intended word flow, as lumps in the throat or bumps on the tongue: Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue.

In the first part of the exhibition is an odd forest of plaster lumps placed on pedestals—a collective of painted bodies that mushroom among O—Overgaden’s existing columns and architecture. The theatrical scene of plaster bulks or heads on stands, partly human-size, echoes the classic stand-in or face double of ‘white power’: the bust, but here the feverishly freewheeling or eccentric motifs refer to fractions of Kitti’s own surroundings, body, and life as a woman of color. The busts are thus nothing like heroic portraiture. The squared chunks are sunken, rough, semi-barren plaster corpses; as if the artistic personae itself has been exploded, scattered, parceled out, and distributed into multiple metaphorical bodies of a fragmented self.

The second part of the exhibition contains works mounted on the wall in O—Overgaden’s historic columned hall. Hung on the wooden panels, aligned with the artist’s upper body, the works function almost as serial self-portraits intermixing jawlines, heads and collar bones with a series of animal and phantasmagoric motifs. This is the stuff of children’s dreams or, equally, of art history, such as a rabbit, a horse, an egg that seemingly grow out of the human physicality or vice versa. As if entering a transgressive state of non-distinction between the human and the animal, reality and dream, the motifs are rough, abstracted and fluid, and drift back and forth. Here seeing is not just seeing. It’s like the old black-and-white duck-rabbit drawings that sway between the two animal motifs if you observe them long enough. Finding the rabbit is potentially difficult; supposedly enhanced creative skills make the shift easier. In Kitti’s case, the distinction is gone. Unplanned and intuitively created, the motifs have merged; a maddening energy has knitted together the haunting childhood fantasies or images from early trauma with the head and the body in which they formed. It is as if the works are asking: how can a human mind or body contain the trauma, the sickness, the disorder—or even, how can society?

For her grand solo show at O—Overgaden, Kitti presents two new work series. One consists of frescoes painted on clunky sculptural surfaces: lumpy plaster molded with hessian cloth, the traditional method for creating portrait busts. The other is a series of wall-hung painted plaster surfaces that zoom in on the upper human torso, throat, and neck, the place from which we try to utter stuff, but also the place where anxiety and depression can form blockages and arrest or (self)censor the intended word flow, as lumps in the throat or bumps on the tongue: Lumps, lumps, lumps become bumps on my tongue.

In the first part of the exhibition is an odd forest of plaster lumps placed on pedestals—a collective of painted bodies that mushroom among O—Overgaden’s existing columns and architecture. The theatrical scene of plaster bulks or heads on stands, partly human-size, echoes the classic stand-in or face double of ‘white power’: the bust, but here the feverishly freewheeling or eccentric motifs refer to fractions of Kitti’s own surroundings, body, and life as a woman of color. The busts are thus nothing like heroic portraiture. The squared chunks are sunken, rough, semi-barren plaster corpses; as if the artistic personae itself has been exploded, scattered, parceled out, and distributed into multiple metaphorical bodies of a fragmented self.

The second part of the exhibition contains works mounted on the wall in O—Overgaden’s historic columned hall. Hung on the wooden panels, aligned with the artist’s upper body, the works function almost as serial self-portraits intermixing jawlines, heads and collar bones with a series of animal and phantasmagoric motifs. This is the stuff of children’s dreams or, equally, of art history, such as a rabbit, a horse, an egg that seemingly grow out of the human physicality or vice versa. As if entering a transgressive state of non-distinction between the human and the animal, reality and dream, the motifs are rough, abstracted and fluid, and drift back and forth. Here seeing is not just seeing. It’s like the old black-and-white duck-rabbit drawings that sway between the two animal motifs if you observe them long enough. Finding the rabbit is potentially difficult; supposedly enhanced creative skills make the shift easier. In Kitti’s case, the distinction is gone. Unplanned and intuitively created, the motifs have merged; a maddening energy has knitted together the haunting childhood fantasies or images from early trauma with the head and the body in which they formed. It is as if the works are asking: how can a human mind or body contain the trauma, the sickness, the disorder—or even, how can society?