Nanna Elvin Hansen

Groundings

27 May - 06 Aug 2023

Nanna Elvin Hansen: Groundings, Installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Nanna Elvin Hansen: Groundings, Installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Nanna Elvin Hansen: Groundings, Installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Nanna Elvin Hansen: Groundings, Installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Nanna Elvin Hansen: Groundings, Installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

Nanna Elvin Hansen: Groundings, Installation view. O – Overgaden, 2023. Photo: David Stjernholm / @david_stjernholm

The practice of the young Danish artist Nanna Elvin Hansen moves in the gray between art, research, and grassroots activism. Building audio and film projects through collaborative processes, her works unveil how structural violence and historical inequality impact human rights and material extraction, as well as human and non-human migration, and displacement.

For her first grand-scale institutional show, Hansen has created the major new film and sound installation Groundings, collaborating with sound artist Eliza Bożek, among others. Based on long-term research on the quartzite quarry at the Giemaš mountain in the Sápmi region of northern Norway, Hansen’s investigation digs into questions of the manmade structures that control Earth’s raw materials and ground—hence the title Groundings. How technology amplifies the mapping, analysis, extraction, and profitability of natural resources and how the core resources employed in these new technologies and shifting geopolitics are the Earth’s raw materials themselves (just think of the chip in your smartphone).

Hansen’s forensic project takes as its point of departure the optical mirrors (also called SiC-optics) used in the satellites that orbit Earth daily. In the filmic prologue, co-produced with data engineer Halfdan Mouritzen, shown on a grand table in the exhibition’s first space, the artist navigates satellite imagery taken from this technology of optics—kind of extreme, augmented ‘eyes’—that makes it possible to ‘see’, surveille, and remotely register the Earth’s soil layers, landmasses, and migrations. The optical mirrors are formed of silicon carbide, an extremely hard material used in heat shields for space rockets. Hansen tracks the silicon carbide optics via the satellite industry’s hi-tech chains of production to their ground substance: the stone quartzite. (In fact, she requested permission from various producers to film the making of the optical mirrors but was refused.) It turns out that one of the world’s largest quartzite quarries, extracting around 850,000 megatons annually, is situated in the former Danish-controlled area of Sápmi in northernmost Norway, by the depopulated village Austertana, close to the Russian and Finnish border. Moreover, it turns out that the largest stockholder of the extraction company is China National BlueStar which plans to expand the mine sixfold. In brief, this is a geopolitical minefield, not least since the local, indigenous Sámi population is still, in part, supported by reindeer herds migrating through the area.

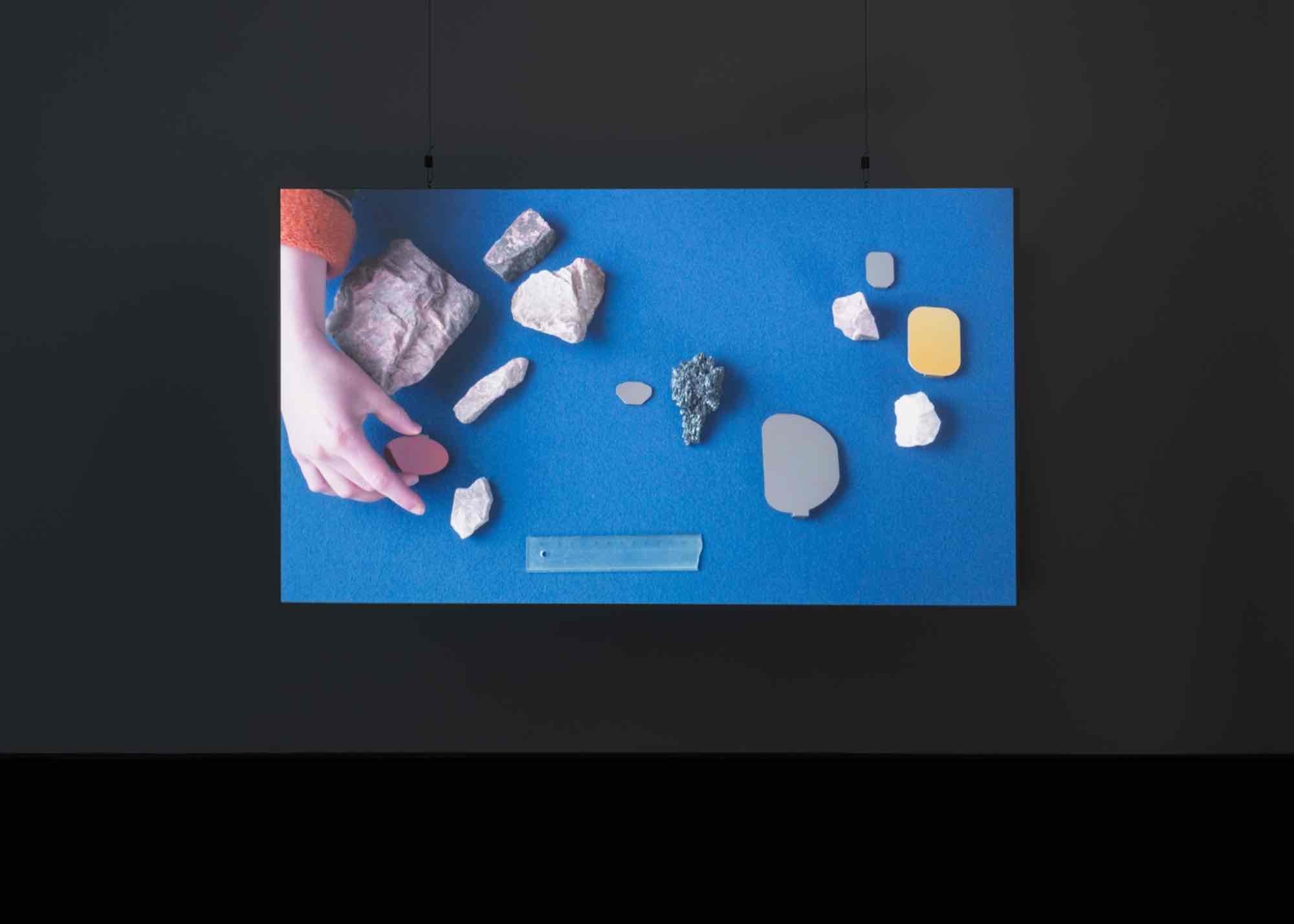

In the main space of the exhibition the quartzite stone is the focal point of an engulfing audiovisual collage. Following the stone as a material witness to the extraction cycle, three grand screens transport the visitor from quartzite to silicon carbide to optical mirrors; from sailing around the quarry at the mountain Giemaš by boat and entering the quarry (right, grand upright screen) via a drone view of migrating reindeer tracks where the company is planning to expand the quarry (grand screen on ground), to a close up of the artist and Bożek’s hands sorting quartzite, silicon carbide, and optical mirrors (left, smaller upright screen). Hansen thus creates a material cross-section of the globally controlled extraction of resources and related questions of consequences for the local ecology, the indigenous population, economic profit, and a wider industry of transnational (satellite) surveillance. The quartzite becomes a point of departure for a forensic and poetic journey, considering how this stone can bear witness to geopolitical exploitation. The exhibition thus asks who—human or non-human—gets to pose political demands and control a landscape?

For her first grand-scale institutional show, Hansen has created the major new film and sound installation Groundings, collaborating with sound artist Eliza Bożek, among others. Based on long-term research on the quartzite quarry at the Giemaš mountain in the Sápmi region of northern Norway, Hansen’s investigation digs into questions of the manmade structures that control Earth’s raw materials and ground—hence the title Groundings. How technology amplifies the mapping, analysis, extraction, and profitability of natural resources and how the core resources employed in these new technologies and shifting geopolitics are the Earth’s raw materials themselves (just think of the chip in your smartphone).

Hansen’s forensic project takes as its point of departure the optical mirrors (also called SiC-optics) used in the satellites that orbit Earth daily. In the filmic prologue, co-produced with data engineer Halfdan Mouritzen, shown on a grand table in the exhibition’s first space, the artist navigates satellite imagery taken from this technology of optics—kind of extreme, augmented ‘eyes’—that makes it possible to ‘see’, surveille, and remotely register the Earth’s soil layers, landmasses, and migrations. The optical mirrors are formed of silicon carbide, an extremely hard material used in heat shields for space rockets. Hansen tracks the silicon carbide optics via the satellite industry’s hi-tech chains of production to their ground substance: the stone quartzite. (In fact, she requested permission from various producers to film the making of the optical mirrors but was refused.) It turns out that one of the world’s largest quartzite quarries, extracting around 850,000 megatons annually, is situated in the former Danish-controlled area of Sápmi in northernmost Norway, by the depopulated village Austertana, close to the Russian and Finnish border. Moreover, it turns out that the largest stockholder of the extraction company is China National BlueStar which plans to expand the mine sixfold. In brief, this is a geopolitical minefield, not least since the local, indigenous Sámi population is still, in part, supported by reindeer herds migrating through the area.

In the main space of the exhibition the quartzite stone is the focal point of an engulfing audiovisual collage. Following the stone as a material witness to the extraction cycle, three grand screens transport the visitor from quartzite to silicon carbide to optical mirrors; from sailing around the quarry at the mountain Giemaš by boat and entering the quarry (right, grand upright screen) via a drone view of migrating reindeer tracks where the company is planning to expand the quarry (grand screen on ground), to a close up of the artist and Bożek’s hands sorting quartzite, silicon carbide, and optical mirrors (left, smaller upright screen). Hansen thus creates a material cross-section of the globally controlled extraction of resources and related questions of consequences for the local ecology, the indigenous population, economic profit, and a wider industry of transnational (satellite) surveillance. The quartzite becomes a point of departure for a forensic and poetic journey, considering how this stone can bear witness to geopolitical exploitation. The exhibition thus asks who—human or non-human—gets to pose political demands and control a landscape?