On the Square

08 Jan - 13 Feb 2010

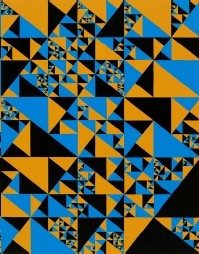

© James Siena

Untitled, 2009

(iterative grid, second version), (19-1/4" x 15-1/8"), both enamel on aluminum

Untitled, 2009

(iterative grid, second version), (19-1/4" x 15-1/8"), both enamel on aluminum

ON THE SQUARE

January 8, 2010 — February 13, 2010

PW 57

More than half a century of artists' meditations on

art history's most elemental form

New York, January 8, 2010—PaceWildenstein is pleased to present a group exhibition that brings together works by some of the most significant artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, paying homage to the square, an elemental form that has helped to define and shape the practice of modern and contemporary art. The exhibition features sculptures and paintings by 16 artists, including Josef Albers, Tara Donovan, Tony Feher, Dan Flavin, Alfred Jensen, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Robert Mangold, Agnes Martin, Louise Nevelson, Ad Reinhardt, Lucas Samaras, Joel Shapiro, James Siena, Keith Tyson, and Corban Walker. On the Square will be on view at the 32 East 57th Street gallery from January 8 through February 13, 2010.

In the late 1960s, Sol LeWitt famously articulated the value of the square’s (or the cube’s) “uninteresting” form: “Released from the necessity of being significant in themselves, they can be better used as grammatical devices from which the work may proceed. The use of a square or cube obviates the necessity of inventing other forms and reserves their use for invention.” Indeed, “the square,” perhaps the most stabile, enduring, and neutral form, a New York art critic argued in her homage to this elemental form in 1967, provides a universal standard that is as attractive in its precision and neutrality to the space age as it was to early philosophers and theologians.”

From deconstruction to reconstruction, creation and re-dissolution[1], for the artists included in this exhibition, the square and its permutations have served as a frame for formal invention. Josef Albers, Alfred Jensen, and Ad Reinhardt used the square as the basic organizing framework for their systems of color theory. Albers once explained that he “prefer[red] to think of the square as a stage on which colors play as actors influencing each other—a visual excitement called interaction.” The arrangement of squares within Albers’Homage to the Squarepaintings and prints were “a convenient carrier” for his color “instrumentation”—a “container for and a dish to serve [his] cooking in.”

The square was an important defining unit for Minimalists and Conceptualists, who used more objective methodologies with mathematical and logic-based systems. Artists such as Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt focusing on spatial organization through sculpture, used the box as the basic unit with which to define real space. “The problem is for any artist to find the concatenation that will grow,” Judd once explained. He emptied space of its inessentials and then re-articulated it with carefully placed objects: closed or open, stacked—vertically or horizontally, placed on the floor, hung on the wall, colored in one or multiple colors; the spacing of the units became as important as the pieces themselves.

The square remains an important element for artists working today. The square enables Joel Shapiro to move fluidly between figuration and abstraction, as he conjoins elongated boxes into evocative constructions. With a nod to minimalism, Tony Feher articulates the repetition of the form in stacked plastic beverage crates (Century Plant, 2002), revealing beauty in the simplest gesture.

The exhibition also includes works by James Siena, Tara Donovan, and Keith Tyson, who use subunits to create works resulting in multiple variations. In pieces such as Tyson’s Geno Pheno Sculpture: “Automata No. 2,” the cube serves as the fundamental component for the phenotype generated by the base. The square is the foundation for James Siena’s enamel on aluminum paintings from 2009, as his visual algorithms cascade into dizzying, pulsating patterns. With the square, a jumble of straight pins finds order and clarity in Tara Donovan’s shimmering Untitled (Pins), 2004.

[1] Ad Reinhardt, “25 Lines of Words on Art Statement,” from It Is (New York), Spring 1958.

January 8, 2010 — February 13, 2010

PW 57

More than half a century of artists' meditations on

art history's most elemental form

New York, January 8, 2010—PaceWildenstein is pleased to present a group exhibition that brings together works by some of the most significant artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, paying homage to the square, an elemental form that has helped to define and shape the practice of modern and contemporary art. The exhibition features sculptures and paintings by 16 artists, including Josef Albers, Tara Donovan, Tony Feher, Dan Flavin, Alfred Jensen, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Robert Mangold, Agnes Martin, Louise Nevelson, Ad Reinhardt, Lucas Samaras, Joel Shapiro, James Siena, Keith Tyson, and Corban Walker. On the Square will be on view at the 32 East 57th Street gallery from January 8 through February 13, 2010.

In the late 1960s, Sol LeWitt famously articulated the value of the square’s (or the cube’s) “uninteresting” form: “Released from the necessity of being significant in themselves, they can be better used as grammatical devices from which the work may proceed. The use of a square or cube obviates the necessity of inventing other forms and reserves their use for invention.” Indeed, “the square,” perhaps the most stabile, enduring, and neutral form, a New York art critic argued in her homage to this elemental form in 1967, provides a universal standard that is as attractive in its precision and neutrality to the space age as it was to early philosophers and theologians.”

From deconstruction to reconstruction, creation and re-dissolution[1], for the artists included in this exhibition, the square and its permutations have served as a frame for formal invention. Josef Albers, Alfred Jensen, and Ad Reinhardt used the square as the basic organizing framework for their systems of color theory. Albers once explained that he “prefer[red] to think of the square as a stage on which colors play as actors influencing each other—a visual excitement called interaction.” The arrangement of squares within Albers’Homage to the Squarepaintings and prints were “a convenient carrier” for his color “instrumentation”—a “container for and a dish to serve [his] cooking in.”

The square was an important defining unit for Minimalists and Conceptualists, who used more objective methodologies with mathematical and logic-based systems. Artists such as Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt focusing on spatial organization through sculpture, used the box as the basic unit with which to define real space. “The problem is for any artist to find the concatenation that will grow,” Judd once explained. He emptied space of its inessentials and then re-articulated it with carefully placed objects: closed or open, stacked—vertically or horizontally, placed on the floor, hung on the wall, colored in one or multiple colors; the spacing of the units became as important as the pieces themselves.

The square remains an important element for artists working today. The square enables Joel Shapiro to move fluidly between figuration and abstraction, as he conjoins elongated boxes into evocative constructions. With a nod to minimalism, Tony Feher articulates the repetition of the form in stacked plastic beverage crates (Century Plant, 2002), revealing beauty in the simplest gesture.

The exhibition also includes works by James Siena, Tara Donovan, and Keith Tyson, who use subunits to create works resulting in multiple variations. In pieces such as Tyson’s Geno Pheno Sculpture: “Automata No. 2,” the cube serves as the fundamental component for the phenotype generated by the base. The square is the foundation for James Siena’s enamel on aluminum paintings from 2009, as his visual algorithms cascade into dizzying, pulsating patterns. With the square, a jumble of straight pins finds order and clarity in Tara Donovan’s shimmering Untitled (Pins), 2004.

[1] Ad Reinhardt, “25 Lines of Words on Art Statement,” from It Is (New York), Spring 1958.