Objects of Wonder

British Sculpture from the Tate Collection 1950s – Present

01 Feb - 27 May 2019

Comprising around seventy masterpieces from Tate’s collection, Objects of Wonder shows how British artists have revolutionized contemporary sculpture since the middle of the twentieth century. The spectrum ranges from icons of postwar modernism like Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, to stars of the Young British Artists generation, including Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin, who is represented with a provocative neon sculpture. The show, conceived exclusively for the PalaisPopulaire, examines important modern and contemporary art movements. A leitmotif that runs through the exhibition is the transformation of everyday objects. Through distortion, recombination, and dramatic staging they become Objects of Wonder that tell stories and put things that were forgotten or only fleetingly perceived in a completely new light.

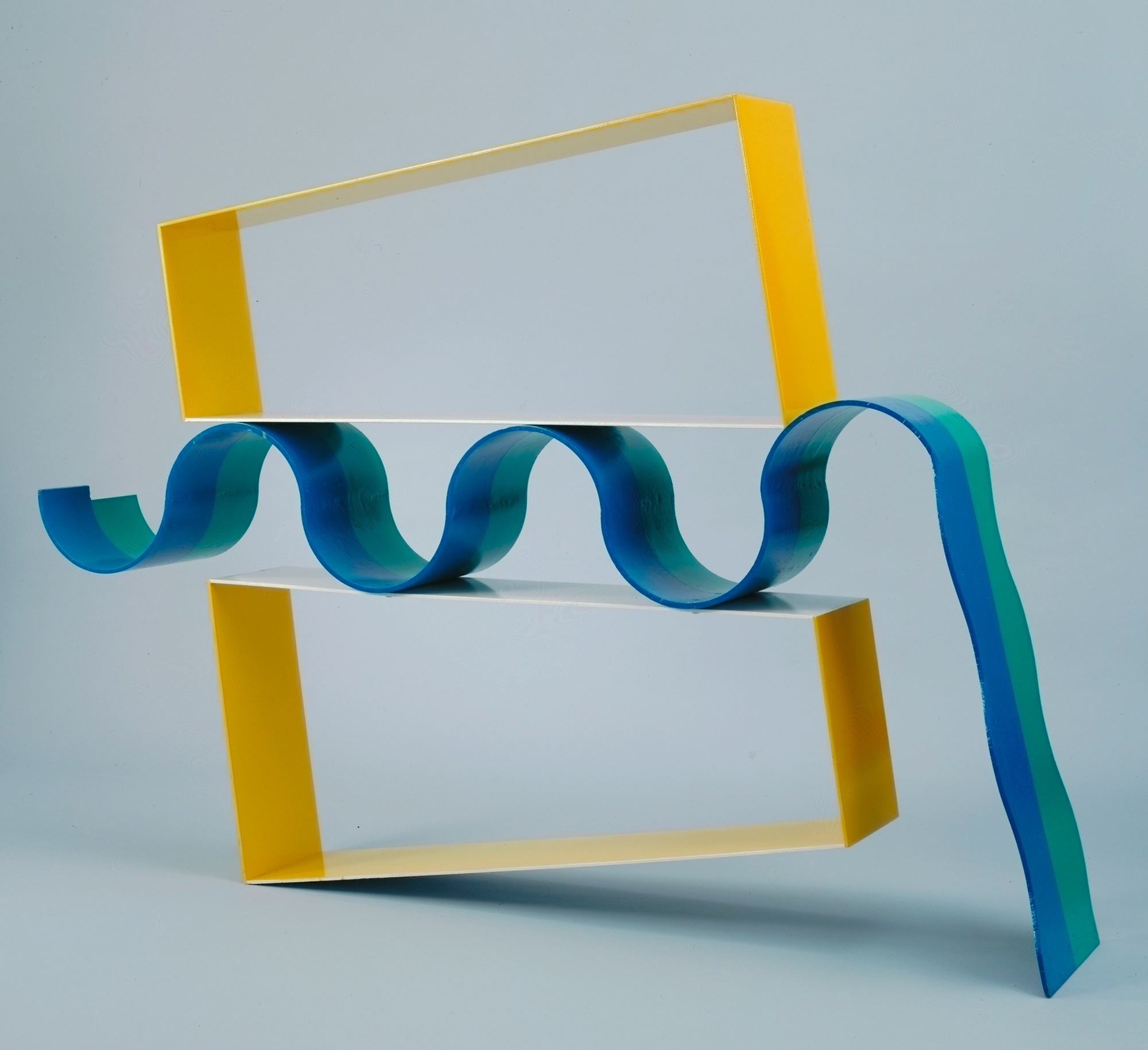

The exhibition begins with Hepworth and Moore as well as the most important sculptors of postwar Britain, including Kenneth Armitage and Elisabeth Frink. All of these artists ushered in the international success of 1950s British sculpture. It continues with the rise of Anthony Caro in the 1960s, whom critics described as the “leading sculptor” of his time. The erstwhile assistant of Moore took sculpture down from its pedestal and onto the floor and created objects by welding together industrial found pieces, steel, and scrap. One example, Yellow Swing (1965), is on view in Objects of Wonder. As a tutor at St. Martin’s School of Art, Caro had a lasting influence on the artists of the so-called New Generation. But in the late 1960s, as a reaction to his formalism, a new movement of young artists emerged that sought to forge stronger links between sculpture and everyday life. Gilbert & George and Richard Long viewed sculpture as an event. It could be a series of postcards, a temporary installation in nature, or a stroll in the landscape. Other artists opposed the formalism in the work of the so-called New Generation sculptors. Phyllida Barlow built giant sculptures and installations from everyday materials such as floor cloths, tarpaulins, timber, and plaster. Paul Neagu, who moved to London from Bucharest in 1970, postulated that sculpture was something that could be apprehended with all the senses. As a teacher Neagu influenced such sculptors as Antony Gormley. And Barlow also taught many artists who would become influential beyond Britain. So too did Richard Wentworth, who instructed a number of the artists counted among the Young British Artists in the 1990s.

The exhibition closes with Turner Prize winner Helen Marten, an artist who combines British sculpture’s traditional interest in the object with twenty-first-century philosophical discourse.

Elena Crippa, Curator of Modern & Contemporary British Art / Daniel Slater, Head of International Collections Exhibitions, Tate London

Alongside the exhibition a catalogue is published.

Organized in collaboration with Tate London.

The exhibition begins with Hepworth and Moore as well as the most important sculptors of postwar Britain, including Kenneth Armitage and Elisabeth Frink. All of these artists ushered in the international success of 1950s British sculpture. It continues with the rise of Anthony Caro in the 1960s, whom critics described as the “leading sculptor” of his time. The erstwhile assistant of Moore took sculpture down from its pedestal and onto the floor and created objects by welding together industrial found pieces, steel, and scrap. One example, Yellow Swing (1965), is on view in Objects of Wonder. As a tutor at St. Martin’s School of Art, Caro had a lasting influence on the artists of the so-called New Generation. But in the late 1960s, as a reaction to his formalism, a new movement of young artists emerged that sought to forge stronger links between sculpture and everyday life. Gilbert & George and Richard Long viewed sculpture as an event. It could be a series of postcards, a temporary installation in nature, or a stroll in the landscape. Other artists opposed the formalism in the work of the so-called New Generation sculptors. Phyllida Barlow built giant sculptures and installations from everyday materials such as floor cloths, tarpaulins, timber, and plaster. Paul Neagu, who moved to London from Bucharest in 1970, postulated that sculpture was something that could be apprehended with all the senses. As a teacher Neagu influenced such sculptors as Antony Gormley. And Barlow also taught many artists who would become influential beyond Britain. So too did Richard Wentworth, who instructed a number of the artists counted among the Young British Artists in the 1990s.

The exhibition closes with Turner Prize winner Helen Marten, an artist who combines British sculpture’s traditional interest in the object with twenty-first-century philosophical discourse.

Elena Crippa, Curator of Modern & Contemporary British Art / Daniel Slater, Head of International Collections Exhibitions, Tate London

Alongside the exhibition a catalogue is published.

Organized in collaboration with Tate London.