Oxidation - Recent Work by Xu Ruotao

28 Jul - 02 Sep 2007

On July 28th, Platform China is pleased to present the exhibition of Xu Ruotao's most recent work, Oxidation, in our main space located in the Caochangdi Art Village, curated by Karen Smith.

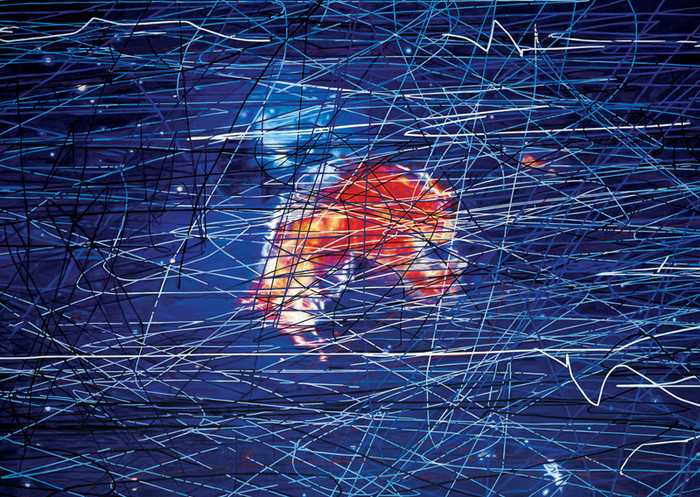

Oxidation is the process of one material reacting to an external force (oxygen), which triggers a (chemical) reaction and, as a result, a change in nature such as burning or rusting. It is an irreversible process.

As a metaphor this signifies the retreat, development or rebirth of the artist himself whether long ago or in recent days. This is the need invoked by one’s heart: to totally submit to one’s inner voice, voluntarily and consciously. It correlates with the Daoist idea of release, of letting go of self, of the ego, which is certainly closer to Xu Ruotao's modus operandi—complying with one’s later change and altered altitude brought about by transformation.

Xu’s artistic past is complexly manifold. Though he began to engage in art at a very young age, one could describe this intermediate period as complicated to the extreme. The countless times that his art has faded in and out of the public eye, encountering many changes throughout this cycle, he’s experienced deeply inherent doubt when discussing his point of view that lead to his many changes of mind.

His earliest doubt came at the beginning of middle school, when he came into contact with the "85 New Wave" art movement. Hence, at that time, he began to turn against traditional art school education. He then left the Luxun Art Academy after having studied there for some years, and later on became one of the first in a group of artists to reside in Yuanmingyuan, which very soon became a village specifically for artists. At that time two main artistic camps had formed, Political Pop and Cynical Realism. As far as the influence that inspired him in those first years as an independent artist, his impulses were evidently less avant-garde than those of many of his peers. Instead, he chose to search in a place that was deeper and more personal for him, if only to discover the answer to a question which he continued to ask himself: what was the reason for the existence of art itself? Unexpectedly, in the winter of 1998, Xu Ruotao returned to the frontlines in his curatorial debut as the co-organizer of the seminal exhibition Corruptionists. It broke the mold of any exhibitions in China that had come before, no matter the form, the space setting, or the concept. Then Xu receded into anonymity again until his 2005 solo exhibition in the China Art and Archives Warehouse curated by Ai Weiwei.

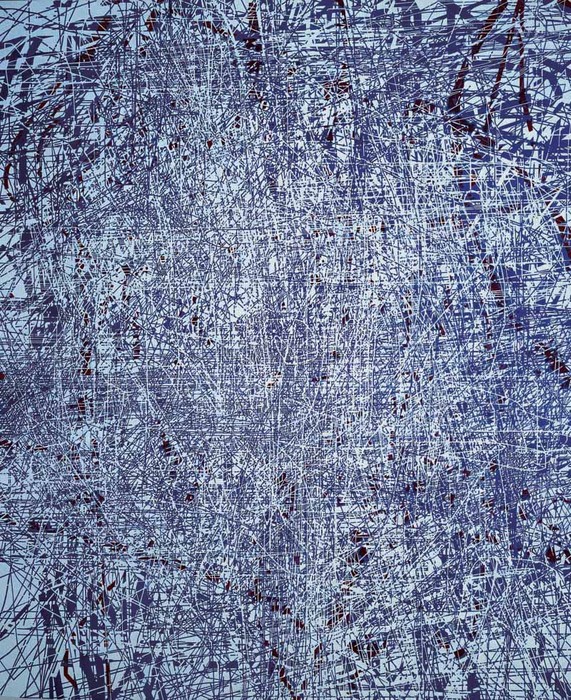

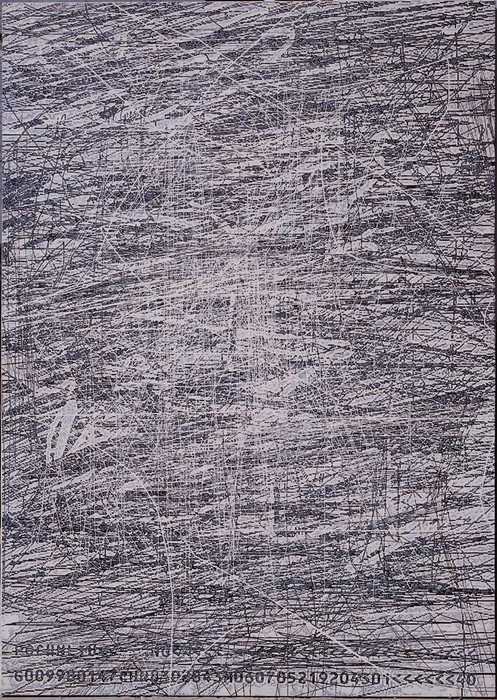

The primary significance of that series was that it helped Xu Ruotao break free of conventional attitudes toward the idea of ‘content’—the self-referencing tendencies of the Chinese avant-garde to create ‘content’ by tying themselves to ‘Chinese’ symbols. Instead, he chose to explore the concept of ‘random’ content, in which space itself serves as the content of the artwork. This allows for a broader discussion about his work, even if that discussion hinges predominantly upon the visual consciousness and abstract mental processes required to explore form and, thus, the formal issues of artistic expression.

Looking back, in one way or another, the groundwork for this group of works has been laid throughout Xu Ruotao’s career, as invisible at the time as the birth of a super nova to the naked eye, and is only revealed in due course, through the passage of time, and to those prepared to look, and watch for the signs. This, too, is not dissimilar to the satisfaction we take in viewing the work: specifically the transformation in visual sensation that is experienced when we first see the work from afar, and then discover a whole new world of content as we draw near and become caught in the web he has woven to entrap us. To date, no other period of creative endeavor has proved so rewarding: none other of his works have allowed him to feel the satisfaction that these paintings achieve. The works are the result of an inspired aesthetic innovation. For the time being at least, the concept stands strong and immutable, and we can only hope, will remain so regardless of what comes next or evolves in the future. The question of furthering the idea could well be problematic: are the lines a clever gimmick and, if overused, might they not assume the role of signifying the artist’s brand? Xu Ruotao does not fear question, nor should he. He has overcome greater challenges in the past. These works are truly worthy of his new-found confidence, and sense of achievement that had previously eluded him far too long.

Oxidation is the process of one material reacting to an external force (oxygen), which triggers a (chemical) reaction and, as a result, a change in nature such as burning or rusting. It is an irreversible process.

As a metaphor this signifies the retreat, development or rebirth of the artist himself whether long ago or in recent days. This is the need invoked by one’s heart: to totally submit to one’s inner voice, voluntarily and consciously. It correlates with the Daoist idea of release, of letting go of self, of the ego, which is certainly closer to Xu Ruotao's modus operandi—complying with one’s later change and altered altitude brought about by transformation.

Xu’s artistic past is complexly manifold. Though he began to engage in art at a very young age, one could describe this intermediate period as complicated to the extreme. The countless times that his art has faded in and out of the public eye, encountering many changes throughout this cycle, he’s experienced deeply inherent doubt when discussing his point of view that lead to his many changes of mind.

His earliest doubt came at the beginning of middle school, when he came into contact with the "85 New Wave" art movement. Hence, at that time, he began to turn against traditional art school education. He then left the Luxun Art Academy after having studied there for some years, and later on became one of the first in a group of artists to reside in Yuanmingyuan, which very soon became a village specifically for artists. At that time two main artistic camps had formed, Political Pop and Cynical Realism. As far as the influence that inspired him in those first years as an independent artist, his impulses were evidently less avant-garde than those of many of his peers. Instead, he chose to search in a place that was deeper and more personal for him, if only to discover the answer to a question which he continued to ask himself: what was the reason for the existence of art itself? Unexpectedly, in the winter of 1998, Xu Ruotao returned to the frontlines in his curatorial debut as the co-organizer of the seminal exhibition Corruptionists. It broke the mold of any exhibitions in China that had come before, no matter the form, the space setting, or the concept. Then Xu receded into anonymity again until his 2005 solo exhibition in the China Art and Archives Warehouse curated by Ai Weiwei.

The primary significance of that series was that it helped Xu Ruotao break free of conventional attitudes toward the idea of ‘content’—the self-referencing tendencies of the Chinese avant-garde to create ‘content’ by tying themselves to ‘Chinese’ symbols. Instead, he chose to explore the concept of ‘random’ content, in which space itself serves as the content of the artwork. This allows for a broader discussion about his work, even if that discussion hinges predominantly upon the visual consciousness and abstract mental processes required to explore form and, thus, the formal issues of artistic expression.

Looking back, in one way or another, the groundwork for this group of works has been laid throughout Xu Ruotao’s career, as invisible at the time as the birth of a super nova to the naked eye, and is only revealed in due course, through the passage of time, and to those prepared to look, and watch for the signs. This, too, is not dissimilar to the satisfaction we take in viewing the work: specifically the transformation in visual sensation that is experienced when we first see the work from afar, and then discover a whole new world of content as we draw near and become caught in the web he has woven to entrap us. To date, no other period of creative endeavor has proved so rewarding: none other of his works have allowed him to feel the satisfaction that these paintings achieve. The works are the result of an inspired aesthetic innovation. For the time being at least, the concept stands strong and immutable, and we can only hope, will remain so regardless of what comes next or evolves in the future. The question of furthering the idea could well be problematic: are the lines a clever gimmick and, if overused, might they not assume the role of signifying the artist’s brand? Xu Ruotao does not fear question, nor should he. He has overcome greater challenges in the past. These works are truly worthy of his new-found confidence, and sense of achievement that had previously eluded him far too long.