Ellsworth Kelly

Windows

27 Feb - 27 May 2019

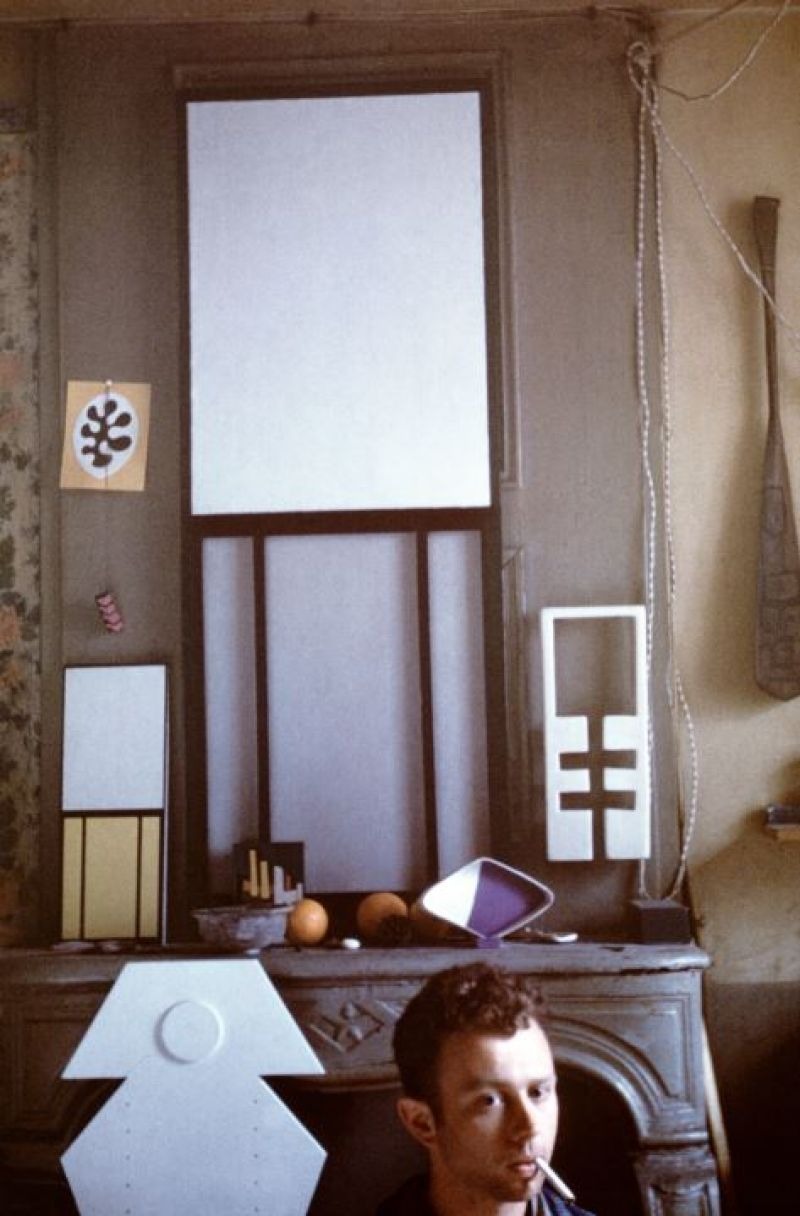

Ellsworth Kelly dans son atelier à l’Hôtel de Bourgogne, 1949 © Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, Spencertown

ELLSWORTH KELLY

Windows

27 February - 27 May 2019

Discover Ellsworth Kelly, a major figure in 20th and 21st century abstract art, through the six Windows made in France between 1949 and 1950, along with a number of paintings, drawings, sketches and photographs. The artist's French years were a period of perpetual invention to which he returned regularly throughout his career.

CURATOR'S POINT OF VIEW

Ellsworth Kelly is one of the major figures of 20th and 21st century abstract art. A few months before his death at 92 years of age on 27 December 2015, the artist donated his most famous work, Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris (1949), to the Centre Pompidou. The work thus returned to the city where it had been created and, in the form of its most recent avatar, the institution whose architecture served as its inspiration. The current exhibition, made possible thanks to close collaboration with the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation (Spencertown, New York), pays tribute to Kelly’s generous gesture by bringing together, for an exceptional event, the six Windows created in France between 1949 and 1950, in addition to a series of related paintings, drawings, sketches and photographs.

Born in Newburgh, New York State in 1923, Ellsworth Kelly studied art at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn from 1941 to 1942, before being enlisted by the US army. He was assigned to special troops, known today as a ghost army, to carry out camouflage operations. He landed in Normandy in June 1944 and participated in the Allied liberation of France, which led him to discover Paris. In 1945, he returned to the USA and attended classes at the Boston Museum of Fine Art, also visiting various major museums on the East coast. His painting at that time was figurative in style. Thanks to a scholarship granted to demobilized soldiers, Kelly moved to Paris in October 1948 and remained there until June 1954. He travelled throughout France, visited the Isenheim altarpiece by Grünewald in Colmar, the Romanesque churches in Poitou-Charentes and became a regular visitor to Parisian museums, in particular the Louvre.

His work rapidly took on an increasingly abstract dimension and during his stay in Belle-Île in 1949, Kelly painted Window 1, a small format in black and white, where the idea of a window exists simply as a structure, an orthogonal intersection, combined elsewhere with the observation of telegraph poles, as a parallel ink-on-paper sketch demonstrates. On his return to Paris, which he explored endlessly, guided by his taste for architecture and its details, the American artist produced Window II, in October/November, a variation of the previous work tinted with a certain anthropomorphism; Window III, an impressive white monochrome for which the drawing, hastily sketched on the back of an envelope, was produced with string sewn onto the canvas, and Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris, a painted construction in wood and canvas which recalls the structure and proportions of a window of the then Musée National d’Art Moderne (the Palais de Tokyo today). This object-painting of almost 1m30 in height marked an aesthetic milestone for Kelly, which he named already made (very different to Duchamp’s ready-made, in that it supposed a duplication with a more or less high ratio of transformation in terms of material, sizes and colours, and not just a simple removal of the object), and was to become the principle behind much of his later production. On this subject, Kelly wrote in his 1969 Notes: ‘After creating Window with two canvases and a wooden frame, I realised that, from now on, painting as I knew it was over for me. Future works should be unsigned, anonymous objects. Everywhere I looked, everything I saw became something to produce; everything had to be exactly as it was, with nothing superfluous. This was a new freedom; I no longer needed to compose. The subject was there, already made and everything was a subject. Everything belonged to me, the glass roof of a factory with its broken and patched up panes, the lines on a road map, the corner of a Braque painting, litter in the street. Everything was the same, everything was suitable.’

A hint of its nature as an object, here the window loses all the connotations of transparency which have been associated with it since the early 15th century and Alberti's De pictura, in which it was assimilated to the painting itself. Kelly makes us consider, and above all see, the window in terms of opacity. This makes his work an essential episode in the consideration of the meaning of abstract art, its particular form of representation and the new relationship it supposes with its viewer. In the first half of 1950, Kelly produced Window V, an oil on wood inspired by the shadows observed through a hotel window and initially designed to be hung, then Window VI, the largest of this sextet of windows. This work was also made of two panels of canvas and wood and was specifically inspired by the window of a Parisian building (the Swiss Pavilion of the University campus, designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in 1930). Kelly’s French years, as the pioneering exhibition at the Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume in 1992-1993 demonstrated, represented a period of perpetual invention which the artist revisited regularly throughout his career. At the heart of the Centre Pompidou, Ellsworth Kelly:Windows brings together some fifty works for the first time and offers a new vision of this milestone period, by focusing on the motif which, so to speak, set the predominant tone. The exhibition includes one exception to the chronology of Kelly’s time in France (1948-1954), with the last, unfinished painting left in his studio on his death, White over Black III (2015). This large-format black and white painting, made up of two elements joined together, is an obvious evocation of the Museum Window, alongside which it will hang for the first time.

In Code couleur n°33, january-april 2019, 28-31

Windows

27 February - 27 May 2019

Discover Ellsworth Kelly, a major figure in 20th and 21st century abstract art, through the six Windows made in France between 1949 and 1950, along with a number of paintings, drawings, sketches and photographs. The artist's French years were a period of perpetual invention to which he returned regularly throughout his career.

CURATOR'S POINT OF VIEW

Ellsworth Kelly is one of the major figures of 20th and 21st century abstract art. A few months before his death at 92 years of age on 27 December 2015, the artist donated his most famous work, Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris (1949), to the Centre Pompidou. The work thus returned to the city where it had been created and, in the form of its most recent avatar, the institution whose architecture served as its inspiration. The current exhibition, made possible thanks to close collaboration with the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation (Spencertown, New York), pays tribute to Kelly’s generous gesture by bringing together, for an exceptional event, the six Windows created in France between 1949 and 1950, in addition to a series of related paintings, drawings, sketches and photographs.

Born in Newburgh, New York State in 1923, Ellsworth Kelly studied art at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn from 1941 to 1942, before being enlisted by the US army. He was assigned to special troops, known today as a ghost army, to carry out camouflage operations. He landed in Normandy in June 1944 and participated in the Allied liberation of France, which led him to discover Paris. In 1945, he returned to the USA and attended classes at the Boston Museum of Fine Art, also visiting various major museums on the East coast. His painting at that time was figurative in style. Thanks to a scholarship granted to demobilized soldiers, Kelly moved to Paris in October 1948 and remained there until June 1954. He travelled throughout France, visited the Isenheim altarpiece by Grünewald in Colmar, the Romanesque churches in Poitou-Charentes and became a regular visitor to Parisian museums, in particular the Louvre.

His work rapidly took on an increasingly abstract dimension and during his stay in Belle-Île in 1949, Kelly painted Window 1, a small format in black and white, where the idea of a window exists simply as a structure, an orthogonal intersection, combined elsewhere with the observation of telegraph poles, as a parallel ink-on-paper sketch demonstrates. On his return to Paris, which he explored endlessly, guided by his taste for architecture and its details, the American artist produced Window II, in October/November, a variation of the previous work tinted with a certain anthropomorphism; Window III, an impressive white monochrome for which the drawing, hastily sketched on the back of an envelope, was produced with string sewn onto the canvas, and Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris, a painted construction in wood and canvas which recalls the structure and proportions of a window of the then Musée National d’Art Moderne (the Palais de Tokyo today). This object-painting of almost 1m30 in height marked an aesthetic milestone for Kelly, which he named already made (very different to Duchamp’s ready-made, in that it supposed a duplication with a more or less high ratio of transformation in terms of material, sizes and colours, and not just a simple removal of the object), and was to become the principle behind much of his later production. On this subject, Kelly wrote in his 1969 Notes: ‘After creating Window with two canvases and a wooden frame, I realised that, from now on, painting as I knew it was over for me. Future works should be unsigned, anonymous objects. Everywhere I looked, everything I saw became something to produce; everything had to be exactly as it was, with nothing superfluous. This was a new freedom; I no longer needed to compose. The subject was there, already made and everything was a subject. Everything belonged to me, the glass roof of a factory with its broken and patched up panes, the lines on a road map, the corner of a Braque painting, litter in the street. Everything was the same, everything was suitable.’

A hint of its nature as an object, here the window loses all the connotations of transparency which have been associated with it since the early 15th century and Alberti's De pictura, in which it was assimilated to the painting itself. Kelly makes us consider, and above all see, the window in terms of opacity. This makes his work an essential episode in the consideration of the meaning of abstract art, its particular form of representation and the new relationship it supposes with its viewer. In the first half of 1950, Kelly produced Window V, an oil on wood inspired by the shadows observed through a hotel window and initially designed to be hung, then Window VI, the largest of this sextet of windows. This work was also made of two panels of canvas and wood and was specifically inspired by the window of a Parisian building (the Swiss Pavilion of the University campus, designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in 1930). Kelly’s French years, as the pioneering exhibition at the Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume in 1992-1993 demonstrated, represented a period of perpetual invention which the artist revisited regularly throughout his career. At the heart of the Centre Pompidou, Ellsworth Kelly:Windows brings together some fifty works for the first time and offers a new vision of this milestone period, by focusing on the motif which, so to speak, set the predominant tone. The exhibition includes one exception to the chronology of Kelly’s time in France (1948-1954), with the last, unfinished painting left in his studio on his death, White over Black III (2015). This large-format black and white painting, made up of two elements joined together, is an obvious evocation of the Museum Window, alongside which it will hang for the first time.

In Code couleur n°33, january-april 2019, 28-31