Wifredo Lam

30 Sep 2015 - 15 Feb 2016

Wifredo Lam

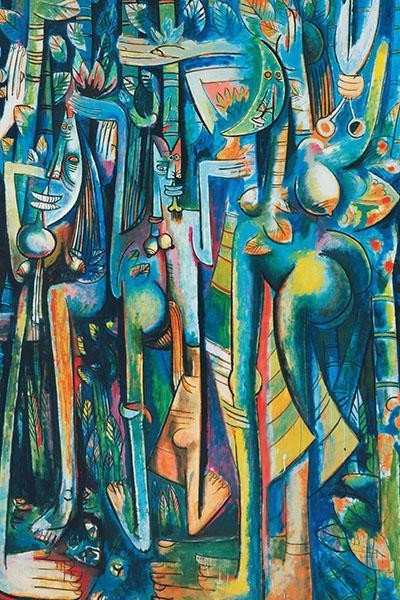

La Jungla, 1943, (détail)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2015

Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

© SDO Wifredo Lam - DR, Adagp, Paris 2015

La Jungla, 1943, (détail)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2015

Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

© SDO Wifredo Lam - DR, Adagp, Paris 2015

WIFREDO LAM

30 September 2015 - 15 February 2016

Curator : Mnam/Cci, Catherine David

For the first time, the Centre Pompidou is devoting a retrospective to the work of Wifredo Lam, with a circuit of nearly 300 works – paintings, drawings, engravings and ceramics – enriched with archives, documents and photographs that illustrate a committed approach in a century full of radical change. Lam's work occupies a singular and paradoxical position in 20th century art. It reflects the diverse movements of forms and ideas in the context of avant-gardes, exchanges and cultural movements – both within themselves and across national borders – that embodied the "broader modernism" described by Andreas Huyssen, but in a different way from the question of globalisation that emerged in the 1990s, and long before it.

Recognised and present from 1940 onwards in private collections and museums, and famous the world over, Lam's work is still subject to considerable misunderstanding and simplistic enthusiasm. While it received attention, encouragement and comments from the key figures he met in Paris during the late Thirties (Picasso, Michel Leiris and André Breton), then in the West Indies, Cuba and Haiti during the Forties (including Aimé Césaire, Fernando Ortiz, Alejo Carpentier, Lydia Cabrera and Pierre Mabille), certain culturalist approaches have altered the perception of a complex output that was invented and structured between several different physical and cultural locations, in conflict with the supposed centre(s) and peripheries of modernity. This exhibition looks back at not only the origins of his work, but also the various stages and situations in which a body of work, patiently constructed between Spain, Paris/Marseille and Cuba, was gradually acknowledged and absorbed into the corpus of canonic modern art.

Found in Spain after the artist's death, the works he produced in the cities where he lived or spent time, abandoned with friends when he hurriedly fled to France after the victory of Franco's armies in the Spanish Civil War, bear witness to a long, hard learning period (1923-1938) in the former colonial metropolis of Madrid, where the young Cuban had gone on a scholarship. He studied the works of the masters in the Prado, together with contemporary, academic and more innovative Spanish painters. His formal choices were eclectic, echoing first fin de siècle and Expressionist aesthetics, then late Cubism: a transnational "syntax" adopted in the Twenties and Thirties by artists all over the world in order to challenge and transform dominant forms and orders. This was an approach where the critical act did not necessarily advocate a formal revolution – at least, according to the terms of a modern canon that claimed to be "universal".

His subjects during those years were conventional (commissioned portraits, landscapes and still lifes). The work of Gris, Miró and Picasso, which Lam discovered in Madrid in March 1929, together with photos of pictures by Gauguin, the German Expressionists and Matisse, which he studied in catalogues and reviews, helped him to simplify his forms and develop a broad brushstroke technique in solid colours. The sudden loss of his wife Eva Piris and his young son to tuberculosis in 1931 and the subsequent ordeals of the Civil War led to a series of mothers-and-children and imploring figures, and a large war scene. During this period he produced many works on paper for economic and practical reasons, but this medium was to remain one of the artist's favourites, and a large number of these pieces were mounted on canvas. With many of the figures executed in 1937 and 1938, at the end of this period in Spain and during his first few months in Paris, faces are replaced by masks (empty, monochrome ovals, or with features reduced to a few geometric lines). These had more to do with a rejection of psychology and forms of Expressionist dramatisation than the arts of Africa, which he discovered in Paris in Picasso's studio and the Musée de l’Homme (which opened in 1938). Two self-portraits are exceptions to this rule: one shows the bust of a mulatto man with bare torso (Autoportrait II, 1938); the other (Autoportrait I, 1937 – not in the exhibition, but reproduced in the catalogue on page 57) shows the face and silhouette of a figure of uncertain gender, with mixed-race features, wearing a flowery kimono. Although simplified, the facial features echo photos of the artist taken at the same period. This play on roles and photographic images provided the first elements in the construction of a self-representation and its successive transformations throughout his life and career, whether he is represented by his own hand or through the lens of photographers (friends like Jesse Fernandez, or famous figures like John Miller and Man Ray). These images helped to build up his figure as a modern artist – Cuban, Latin American and international – according to different periods, perceptions and circumstances.

With a Chinese father from Canton and a mulatto mother descended from slaves and Spaniards, Wifredo Lam became aware very young of the racial question and its social and political implications in Cuba, Europe and later the United States. In his letters from Spain to his family and his friend Balbina Barrera, on top of the daily problems due to an often precarious life and anxiety due to the increasing danger, he expressed a persistent, vague unease that he soon identified directly with the colonial condition, particularly through his friendship and exchanges with Aimé Césaire, who published his Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (illustrated by Lam) in 1940. However, his Marxist readings and the convictions he developed during the Spanish war, together with European anti-fascism, focused his attention – probably as much as his Sino-African origins – on the links between class and domination more than on racial thinking and "Negritude". He became integrated into various national, social and cultural realms, though not without friction, but always maintained a distance without ever being deceived by the roles and projections in terms of identity imposed on him by well-intentioned friends and admirers. For example, Picasso's famous joke, when he exclaimed, seeing the pictures Lam showed him on his arrival in Paris – "He has the right; he's a Negro!" – instantly equated his work with primitivism/authenticity and a supposed "African" heritage hastily associated with the colour of his skin.

In the same way as the friendship and support of Picasso, of whom he was never the "pupil", the friendship of André Breton and the Surrealist movement led to simplistic interpretations of Lam's work. When he met André Breton and Benjamin Péret in late 1939, Surrealism's heyday, in terms of heroism and theory, was now past; the movement, worn out by polemics and internal divisions, was seeking a new lease of life, which it would find in the Americas (Mexico, the West Indies and New York) and the arts of Oceania. The arrival of German troops in Paris and the group's flight to Marseille intensified the bonds of friendship, and fostered the revival of collective activities, such as cadavres exquis and the creation of new playing cards for the "Jeu de Marseille". Lam took part in these sessions and produced numerous Indian ink drawings in notebooks that were subsequently broken up. These line drawings borrowed various elements from the worlds of humans, animals and plants and recomposed them into hybrid figures, prefiguring the works of his return to Cuba. In this period of uncertainty and anxiety, which brought short the "new beginning" in Paris, automatic practices also liberated his psychic and formal energies while he was awaiting a visa and a boat to take him into exile. After twenty years spent in Europe and two flights, Lam saw his forced return to his "native land" as a painfully frustrating exile. He rediscovered a country he had left when he was very young, where corruption, racism and poverty were rife in the police-led reign of terror under Gerardo Machado. This was Hemingway's Cuba: the paradise of gambling, prostitution and cigars. The island had been independent since 1982, but centuries of colonial exploitation had wrecked a culture now struggling to resist, beneath the folklore of cheap trash encouraged by a cynical power.

1942 was a year of intense work, and La Jungle, completed in January 1943, was exhibited in June 1944 in the second show devoted to Lam by the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York. It was then bought by James Johnson Sweeney for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The fact that the painting was hung for many years in the corridor leading to the museum's cloakroom, before it joined the Demoiselles d’Avignon in the exhibition rooms, illustrates the resistance of the modern canon laid down by the great Western institutions, and maintained in them. Because even if La Jungle was immediately acknowledged as a major work, it was unable to find a place in the linear discourse of a "modern art" limited to the work of Euro-American metropolises. In contrast, the work's acceptance in Cuba was immediate and remarkable, in a period that was politically tense but highly active in cultural and intellectual terms. On his return to the island, Lam lived in relative "insilio" (internal exile) in the house/studio in Marianao, where he found his friends Pierre Loeb and Pierre Mabille again, together with Alejo Carpentier, Lydia Cabrera, Fernando Ortiz, Virgilio Piñera and José Lezama Lima. His long stay in Europe had distanced him from the groups and issues of the island's avant-gardes during the Twenties and Thirties, but the friendly instruction of Lydia Cabrera, who was continuing to collect the traditions and rituals of Santería (which she published in El Monte in 1954), and his reading of Fernando Ortiz, who had recently published Contrepoint cubain du tabac et du sucre (1940) inventing the fundamental concept of "transculturation" long before the idea of "tout-monde" and other multicultural generalities, helped him to (re-)discover Afro-Cuban culture and the extraordinary tropical plant life. These explorations were part of a broader context of cultural resistance to the strategies of internal domination ("dictatorship") and external domination (Americanisation), and the search for an essential "Cubanity" – though one lacking essentialism, because with no "origin" (after the destruction of the indigenous populations during the conquest), this was a sociological, historical and political matter rather than an aesthetic one.

In his first monograph on the artist, Fernando Ortiz puts forward an iconographic interpretation of La Jungle and the works of the 1940s, clarifying their formal and symbolic references to Afro-Cuban beliefs and exuberant tropical vegetation, together with the symbols borrowed from the occultist tradition, in which Lam shared an interest with his wife Helena Holzer and Pierre Mabille. He also emphasises a "hermetic style" and certain "dealings" with the invisible, and things remaining watchful beneath appearances. In a text written in Rome in 1954, María Zambrano evokes the "secrecy" and disturbing silence emanating from the highly singular, almost kinetic luminosity of Lam's works in the Forties: "For in tropical nature, everything moves beneath an apparent tranquillity; only the night reveals the hidden festivities and the dance that seem to permeate the private life of all creatures. The world of the tropics is not visual; it is musical and Orphic. Lam's painting reveals this secret; his pictures have a musical, rhythmic distribution. The space is the void displaced by subtle bodies as they whirl around."

Wifredo Lam knew that there was no jungle in Cuba, only the manigua: a dense and thorny scrub. And the figures watching at the entrance to this dark wood belong to the monte, the symbolic and sacred space that encapsulates the historical memory of the "Cimarrones" (runaway black slaves) who escaped from plantations in the times of slavery, for whom it was a refuge, the eternal abode of spirits, as well as the future of rebellion. Political experience as much as poetic intuition told Lam that it "would take time" for his work to circulate and reach (in every sense of the term) all those for whom he intended it.

30 September 2015 - 15 February 2016

Curator : Mnam/Cci, Catherine David

For the first time, the Centre Pompidou is devoting a retrospective to the work of Wifredo Lam, with a circuit of nearly 300 works – paintings, drawings, engravings and ceramics – enriched with archives, documents and photographs that illustrate a committed approach in a century full of radical change. Lam's work occupies a singular and paradoxical position in 20th century art. It reflects the diverse movements of forms and ideas in the context of avant-gardes, exchanges and cultural movements – both within themselves and across national borders – that embodied the "broader modernism" described by Andreas Huyssen, but in a different way from the question of globalisation that emerged in the 1990s, and long before it.

Recognised and present from 1940 onwards in private collections and museums, and famous the world over, Lam's work is still subject to considerable misunderstanding and simplistic enthusiasm. While it received attention, encouragement and comments from the key figures he met in Paris during the late Thirties (Picasso, Michel Leiris and André Breton), then in the West Indies, Cuba and Haiti during the Forties (including Aimé Césaire, Fernando Ortiz, Alejo Carpentier, Lydia Cabrera and Pierre Mabille), certain culturalist approaches have altered the perception of a complex output that was invented and structured between several different physical and cultural locations, in conflict with the supposed centre(s) and peripheries of modernity. This exhibition looks back at not only the origins of his work, but also the various stages and situations in which a body of work, patiently constructed between Spain, Paris/Marseille and Cuba, was gradually acknowledged and absorbed into the corpus of canonic modern art.

Found in Spain after the artist's death, the works he produced in the cities where he lived or spent time, abandoned with friends when he hurriedly fled to France after the victory of Franco's armies in the Spanish Civil War, bear witness to a long, hard learning period (1923-1938) in the former colonial metropolis of Madrid, where the young Cuban had gone on a scholarship. He studied the works of the masters in the Prado, together with contemporary, academic and more innovative Spanish painters. His formal choices were eclectic, echoing first fin de siècle and Expressionist aesthetics, then late Cubism: a transnational "syntax" adopted in the Twenties and Thirties by artists all over the world in order to challenge and transform dominant forms and orders. This was an approach where the critical act did not necessarily advocate a formal revolution – at least, according to the terms of a modern canon that claimed to be "universal".

His subjects during those years were conventional (commissioned portraits, landscapes and still lifes). The work of Gris, Miró and Picasso, which Lam discovered in Madrid in March 1929, together with photos of pictures by Gauguin, the German Expressionists and Matisse, which he studied in catalogues and reviews, helped him to simplify his forms and develop a broad brushstroke technique in solid colours. The sudden loss of his wife Eva Piris and his young son to tuberculosis in 1931 and the subsequent ordeals of the Civil War led to a series of mothers-and-children and imploring figures, and a large war scene. During this period he produced many works on paper for economic and practical reasons, but this medium was to remain one of the artist's favourites, and a large number of these pieces were mounted on canvas. With many of the figures executed in 1937 and 1938, at the end of this period in Spain and during his first few months in Paris, faces are replaced by masks (empty, monochrome ovals, or with features reduced to a few geometric lines). These had more to do with a rejection of psychology and forms of Expressionist dramatisation than the arts of Africa, which he discovered in Paris in Picasso's studio and the Musée de l’Homme (which opened in 1938). Two self-portraits are exceptions to this rule: one shows the bust of a mulatto man with bare torso (Autoportrait II, 1938); the other (Autoportrait I, 1937 – not in the exhibition, but reproduced in the catalogue on page 57) shows the face and silhouette of a figure of uncertain gender, with mixed-race features, wearing a flowery kimono. Although simplified, the facial features echo photos of the artist taken at the same period. This play on roles and photographic images provided the first elements in the construction of a self-representation and its successive transformations throughout his life and career, whether he is represented by his own hand or through the lens of photographers (friends like Jesse Fernandez, or famous figures like John Miller and Man Ray). These images helped to build up his figure as a modern artist – Cuban, Latin American and international – according to different periods, perceptions and circumstances.

With a Chinese father from Canton and a mulatto mother descended from slaves and Spaniards, Wifredo Lam became aware very young of the racial question and its social and political implications in Cuba, Europe and later the United States. In his letters from Spain to his family and his friend Balbina Barrera, on top of the daily problems due to an often precarious life and anxiety due to the increasing danger, he expressed a persistent, vague unease that he soon identified directly with the colonial condition, particularly through his friendship and exchanges with Aimé Césaire, who published his Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (illustrated by Lam) in 1940. However, his Marxist readings and the convictions he developed during the Spanish war, together with European anti-fascism, focused his attention – probably as much as his Sino-African origins – on the links between class and domination more than on racial thinking and "Negritude". He became integrated into various national, social and cultural realms, though not without friction, but always maintained a distance without ever being deceived by the roles and projections in terms of identity imposed on him by well-intentioned friends and admirers. For example, Picasso's famous joke, when he exclaimed, seeing the pictures Lam showed him on his arrival in Paris – "He has the right; he's a Negro!" – instantly equated his work with primitivism/authenticity and a supposed "African" heritage hastily associated with the colour of his skin.

In the same way as the friendship and support of Picasso, of whom he was never the "pupil", the friendship of André Breton and the Surrealist movement led to simplistic interpretations of Lam's work. When he met André Breton and Benjamin Péret in late 1939, Surrealism's heyday, in terms of heroism and theory, was now past; the movement, worn out by polemics and internal divisions, was seeking a new lease of life, which it would find in the Americas (Mexico, the West Indies and New York) and the arts of Oceania. The arrival of German troops in Paris and the group's flight to Marseille intensified the bonds of friendship, and fostered the revival of collective activities, such as cadavres exquis and the creation of new playing cards for the "Jeu de Marseille". Lam took part in these sessions and produced numerous Indian ink drawings in notebooks that were subsequently broken up. These line drawings borrowed various elements from the worlds of humans, animals and plants and recomposed them into hybrid figures, prefiguring the works of his return to Cuba. In this period of uncertainty and anxiety, which brought short the "new beginning" in Paris, automatic practices also liberated his psychic and formal energies while he was awaiting a visa and a boat to take him into exile. After twenty years spent in Europe and two flights, Lam saw his forced return to his "native land" as a painfully frustrating exile. He rediscovered a country he had left when he was very young, where corruption, racism and poverty were rife in the police-led reign of terror under Gerardo Machado. This was Hemingway's Cuba: the paradise of gambling, prostitution and cigars. The island had been independent since 1982, but centuries of colonial exploitation had wrecked a culture now struggling to resist, beneath the folklore of cheap trash encouraged by a cynical power.

1942 was a year of intense work, and La Jungle, completed in January 1943, was exhibited in June 1944 in the second show devoted to Lam by the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York. It was then bought by James Johnson Sweeney for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The fact that the painting was hung for many years in the corridor leading to the museum's cloakroom, before it joined the Demoiselles d’Avignon in the exhibition rooms, illustrates the resistance of the modern canon laid down by the great Western institutions, and maintained in them. Because even if La Jungle was immediately acknowledged as a major work, it was unable to find a place in the linear discourse of a "modern art" limited to the work of Euro-American metropolises. In contrast, the work's acceptance in Cuba was immediate and remarkable, in a period that was politically tense but highly active in cultural and intellectual terms. On his return to the island, Lam lived in relative "insilio" (internal exile) in the house/studio in Marianao, where he found his friends Pierre Loeb and Pierre Mabille again, together with Alejo Carpentier, Lydia Cabrera, Fernando Ortiz, Virgilio Piñera and José Lezama Lima. His long stay in Europe had distanced him from the groups and issues of the island's avant-gardes during the Twenties and Thirties, but the friendly instruction of Lydia Cabrera, who was continuing to collect the traditions and rituals of Santería (which she published in El Monte in 1954), and his reading of Fernando Ortiz, who had recently published Contrepoint cubain du tabac et du sucre (1940) inventing the fundamental concept of "transculturation" long before the idea of "tout-monde" and other multicultural generalities, helped him to (re-)discover Afro-Cuban culture and the extraordinary tropical plant life. These explorations were part of a broader context of cultural resistance to the strategies of internal domination ("dictatorship") and external domination (Americanisation), and the search for an essential "Cubanity" – though one lacking essentialism, because with no "origin" (after the destruction of the indigenous populations during the conquest), this was a sociological, historical and political matter rather than an aesthetic one.

In his first monograph on the artist, Fernando Ortiz puts forward an iconographic interpretation of La Jungle and the works of the 1940s, clarifying their formal and symbolic references to Afro-Cuban beliefs and exuberant tropical vegetation, together with the symbols borrowed from the occultist tradition, in which Lam shared an interest with his wife Helena Holzer and Pierre Mabille. He also emphasises a "hermetic style" and certain "dealings" with the invisible, and things remaining watchful beneath appearances. In a text written in Rome in 1954, María Zambrano evokes the "secrecy" and disturbing silence emanating from the highly singular, almost kinetic luminosity of Lam's works in the Forties: "For in tropical nature, everything moves beneath an apparent tranquillity; only the night reveals the hidden festivities and the dance that seem to permeate the private life of all creatures. The world of the tropics is not visual; it is musical and Orphic. Lam's painting reveals this secret; his pictures have a musical, rhythmic distribution. The space is the void displaced by subtle bodies as they whirl around."

Wifredo Lam knew that there was no jungle in Cuba, only the manigua: a dense and thorny scrub. And the figures watching at the entrance to this dark wood belong to the monte, the symbolic and sacred space that encapsulates the historical memory of the "Cimarrones" (runaway black slaves) who escaped from plantations in the times of slavery, for whom it was a refuge, the eternal abode of spirits, as well as the future of rebellion. Political experience as much as poetic intuition told Lam that it "would take time" for his work to circulate and reach (in every sense of the term) all those for whom he intended it.