Monique Prieto

26 Jan - 08 Mar 2008

MONIQUE PRIETO

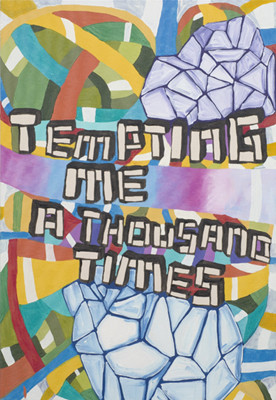

In the decade following her emergence from CalArts in 1994, Monique Prieto started a succesful early career founded on colurful abstraction and computer-based painting. In 2003, introducing text in her painting, she proceeded to a radical turn in her work and starts to use language as an image. Those text paintings, which can be described as messy pictures with letters made up of hand-drawn, black-and-white blocks that spell out phrases from the diary of Samuel Pepys.

« I wanted to bring black back into the paintings, which was a color I had completely left out for the previous ten years. And then I wanted to reflect the historical moment, I wanted to let my very conscious awareness of the times be reflected in the work», Prieto explained in a conversation with Thomas Lawson. There are many ways to be political and to act political, sharing the personal through the use of language is her option. « I knew I was going to use words, and I wanted to keep it personal... but outside of myself. » Then Prieto happened upon the diary of Samuel Pepys. An seventeenth-century administrator in the British navy and a member of Parliament, Pepys is best known today for his detailed, firsthand accounts of major historic events, as well as his private and often mundane accounts of his everyday life. « It’s completely banal, it’s personal on a level that transcends the centuries and the genders and the class issues. »

The right words being found, the manner to represent them wasn’t long to wait for. On the freeway, stuck in the traffic, a graffiti appears to her on the side of the road but she’s unable to read it. « I wanted to read it, I tried to read it, I kept trying to read it.» She came back a few days later, but it was gone. « It disappeared. But it engaged me for that moment very intensely. Anyway, that inspired me to come home and just make some drawings with words. » Like the graffiti, the words in the prints are difficult to decipher and can be experienced both as abstract form and readable text. The awkwardly thick and blocky letters and the wild layout make the text intentionaly hard to read so that the viewer stumbles and stutters from top to bottom. One is forced to sound out the words, like a child learning to read. The meanings that emerge requires the participation of the viewer.

With the utilisation of a technique inspired by street art, Prieto is bringing Pepys’ words into the 21st century, and is giving his thoughts a form helping them to find a new potential for meaning. Anyway the process of interpretation couldn’t be completely fulfilled, as the fragmentary nature of a quotation isolated from its contexts causes disorientation. The disconcerting aspect of her work being very important to her, she inflicts it to herself. In the most recents paintings, showed in the exhibition, the freely painted area gains in importance and changes appearance. She tells that in an effort to move outside of her usual range of command, she resorted to purposely difficult and unnatural color choices, brushwork and paint consistency, creating herself formal problems. And even if those areas are the place where she wants to paint thoughts about the words, she engaged herself to represent a content which, like the word’s meanings, is fragmentary and can’t be fixed. This enigmatic aspect with regards to both content and form contributes to situate the work in a space halfway between representation and abstraction. Something is pictured, but it’s not clear what. Language becomes the ultime form of abstraction.

In the decade following her emergence from CalArts in 1994, Monique Prieto started a succesful early career founded on colurful abstraction and computer-based painting. In 2003, introducing text in her painting, she proceeded to a radical turn in her work and starts to use language as an image. Those text paintings, which can be described as messy pictures with letters made up of hand-drawn, black-and-white blocks that spell out phrases from the diary of Samuel Pepys.

« I wanted to bring black back into the paintings, which was a color I had completely left out for the previous ten years. And then I wanted to reflect the historical moment, I wanted to let my very conscious awareness of the times be reflected in the work», Prieto explained in a conversation with Thomas Lawson. There are many ways to be political and to act political, sharing the personal through the use of language is her option. « I knew I was going to use words, and I wanted to keep it personal... but outside of myself. » Then Prieto happened upon the diary of Samuel Pepys. An seventeenth-century administrator in the British navy and a member of Parliament, Pepys is best known today for his detailed, firsthand accounts of major historic events, as well as his private and often mundane accounts of his everyday life. « It’s completely banal, it’s personal on a level that transcends the centuries and the genders and the class issues. »

The right words being found, the manner to represent them wasn’t long to wait for. On the freeway, stuck in the traffic, a graffiti appears to her on the side of the road but she’s unable to read it. « I wanted to read it, I tried to read it, I kept trying to read it.» She came back a few days later, but it was gone. « It disappeared. But it engaged me for that moment very intensely. Anyway, that inspired me to come home and just make some drawings with words. » Like the graffiti, the words in the prints are difficult to decipher and can be experienced both as abstract form and readable text. The awkwardly thick and blocky letters and the wild layout make the text intentionaly hard to read so that the viewer stumbles and stutters from top to bottom. One is forced to sound out the words, like a child learning to read. The meanings that emerge requires the participation of the viewer.

With the utilisation of a technique inspired by street art, Prieto is bringing Pepys’ words into the 21st century, and is giving his thoughts a form helping them to find a new potential for meaning. Anyway the process of interpretation couldn’t be completely fulfilled, as the fragmentary nature of a quotation isolated from its contexts causes disorientation. The disconcerting aspect of her work being very important to her, she inflicts it to herself. In the most recents paintings, showed in the exhibition, the freely painted area gains in importance and changes appearance. She tells that in an effort to move outside of her usual range of command, she resorted to purposely difficult and unnatural color choices, brushwork and paint consistency, creating herself formal problems. And even if those areas are the place where she wants to paint thoughts about the words, she engaged herself to represent a content which, like the word’s meanings, is fragmentary and can’t be fixed. This enigmatic aspect with regards to both content and form contributes to situate the work in a space halfway between representation and abstraction. Something is pictured, but it’s not clear what. Language becomes the ultime form of abstraction.