David Ratcliff

13 Nov - 23 Dec 2010

© David Ratcliff

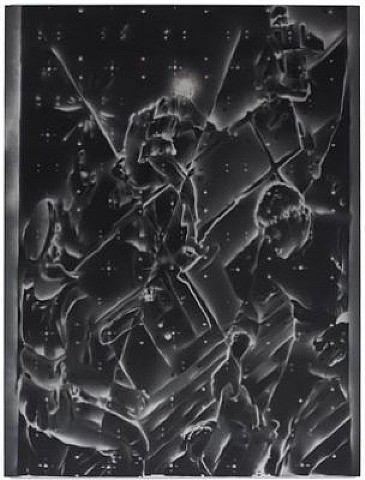

Untitled Ghost Painting (titanic), 2010

Spray paint on canvas

163 x 122 cm / 64.2 x 48 in

Untitled Ghost Painting (titanic), 2010

Spray paint on canvas

163 x 122 cm / 64.2 x 48 in

DAVID RATCLIFF

"Ghost Paintings"

Nov 13 - Dec 23, 2010

Vernissage le 13.11.2010 de 18:00 à 21:00 h

Opening: Saturday 13.11.2010 from 2 to 8 pm

English version. Scroll down for French and Dutch versions

Giving Up the Ghost: A Conversation With David Ratcliff

BN: An apparition, a spectral image of a figure, seems by now central to all your work. The sense that you conjure images that are haunting, and sometimes terrifying, or recur in memory, pervades your practice. Even the earliest, more pop-inflected paintings are like after-images: representations and fragments that are layered and collide to suggest that seeing is not always believing, that sometimes all we have is a trace that is about to vanish into thin air. With these new works, explicitly referred to as Ghost Paintings, once again by means of a particular de-composition, you haunt the image to even greater effect.

DR: The Ghost Paintings started out as a way to bring drawing into the paintings, to move outside of the photographic forms. I had started using, and still often use, photos of drawings from online sources, but at some point I began to re-trace them, or trace the edges of photographic elements with a narrower line. So while they have become fainter, less concrete entities, they've simultaneously bridged the distance my hand has traditionally had from the work. As you said, I haunt the images in a way I'd previously resisted. The tracings are then re-traced with a knife on paper, and it is this knife tracing that is ultimately transferred to the canvas.

BN: I didn't know that you use a knife. In fact, I was going to say that the line in these new paintings reminds me of the cut paper silhouettes of Kara Walker, as well as the slicing of paper "screens" or curtains in the videos of Alex Hubbard. These works are either clearly figurative or abstract, but your paintings are always hybridized, hovering between abstraction and the representation. It's curious to think of your work as related to experimental film, particularly to color and light studies. As befits their overall designation, the paintings do seem dream-like, as if recalled from the unconscious. Who are some of the artists haunting your studio lately?

DR: On my desk right now I've got books and catalogs by Wolfgang Tillmans, Joan Didion, and Sigmar Polke, all of whom trace the layered contours of contemporary society in four dimensions, and all of whom deal with different "ghost" manifestations.

BN: That's an artist who makes photographs, a writer who is one of our keenest observers, and a great alchemist — recently departed. Polke, with whom all your work clearly resonates, is a painter whose sensibility comes to bear much more on a younger generation of American artists than on Europeans, probably because of the convergence of Pop and the psychedelic. But Tillmans, who I admire, isn't someone I associate with your image investigation. And I'm not sure I follow the "four dimensions" remark. Can you talk about that, and about how it is that you are choosing the imagery your work with.

DR: Tillmans's installations are probably the most complete expressions of personal and public life in contemporary society, and I view them similarly to my experience of the internet ... mainly in their astounding combinations of elements that in no way discourages viewer inclusion. He's on par with Joan Didion in how they're both, as you say, keen observers, taking in the world around them over time rather than in an instant. That's another thing I love about Tillmans — how his installations include time in a way that feels important. And of course looming behind it all is "history," which is like a phantom.

Some of the Ghost Paintings are composed using groups of images I'd collected years ago. At the time, I was engaged in very hands-off random searches, and to a degree my image-gathering process has remained deliberately loose because there's no way to anticipate what you come across. Over the past year, I've found myself more drawn to images that tend to highlight the rapidly changing world. Very recent images, as well as those from the past, that contrast with how we want to see things now. I've started using coloring book images from bible stories or from historical events. In coloring-book form, these stories and events tend to empty themselves out and simultaneously open up to a broader spectrum of society. There's something in the simplicity of the outline that I'm drawn to. In searching for images for these new paintings I'm really looking at outlines, at the edges of forms. The interior becomes less important since I'm not even sure it will be made visible. I've used an image from the Vietnam war, for example, a snapshot taken in 1966, of American soldiers posing in front of a group of terrified monks. The soldiers have praying hands and V-for-victory signs, while the monks look really shit-scared. Behind them, a tank has "I'm the god of hell fire!" hand-written on the front.

BN: This is the painting you titled I'm the God of Hell Fire? I don't see almost any of what you're describing.

DR: Right, because in the final painting all you can see is the outline. You can't tell that they're Buddhist monks, and you can't tell that they're American soldiers. They're obviously a group of young men, and they're shirtless, but that's about all that's visible. They're not just from the past. They're gone.

BN: Vietnam makes me think of the painting Swimsuit Napalm. It looks like many images that have been carved and compressed into a single block of milky marble that is somehow melting. The painting is action-packed but elusive, as if the density is an apparition: here, you've converged all-over composition with the monochrome.

DR: Like many people, I tend to experience memory in monochrome. Maybe it's partly my generation, when a lack of color signified the past. Growing up we still had a black-and-white TV in the house. Late night on all the channels, when the programs were finished, there were only color-bars or dense and airy static fuzz. An attraction to the past is something that I need to resist in my work since I'm afraid I'll get it all wrong, but then there is that phantom, that continuum. The paintings tend to look like afterimages of events gone by more than premonitions of events to come. The work you're talking about formally resembles Cubism, but as you said, it's like an apparition, so instead of coming up against hard aggression you enter a more anemic version, as if it's seen through water, or a gravestone rubbing.

BN: At first glance, your work doesn't seem to embody a new form of history painting, and yet it does, certainly in terms of an artist engaged in a "coming to grips" with the presence of the past. In your case, the idea of painting history becomes a recording of something that is happening again: history as a revolving door in which figures and events get jammed up and spun around and ejected. Which is how they appear in the appropriately titled Payday.

DR: Absolutely. Whenever I find myself responding to events from the past it's because I'm responding to them now. If they're not happening currently, in the present day in some form, past events don't really register for me. I don't remember what I just read unless it's got that trigger, that flash of recognition. It might be a by-product of the fact that all the images I use come from online sources, and in shifting through the pool you tend to see the same things over and over again, copies of copies of copies, and with the prevalence of facebook, these repeats are showing up in "real life." Not to say that copies don't work. Payday has it's roots in an eastern-Eurpoean cartoon dealing with immigration and migrant labor. But who is getting paid, and what pay means, is difficult to say when it looks like a massacre.

BN: You might have identified the source of the image as a press photo of a bombing in Iraq, and I wouldn't have any reason not to believe you. Or a bombing image overlaid with figures from a bible story in a coloring-book, which wouldn't be that bizarre, actually, and would offer a perfect example of how you visually articulate feelings that otherwise leave the viewer speechless. Many artists have offered us "the horrors of war" — Thomas Hirschhorn being an obvious recent example — and yet these are almost always mere representations. Your images don't show us how things look so much as how they are absorbed and persist on a visceral and emotional level. I find that the poetics and politics of art overlap in the notion that, as the confessional poet and suicide Anne Sexton once remarked, "Misery from a distance resembles beauty." This coincides with Breton's now-famous declaration: "Beauty will be convulsive or not at all." In a painting like Pharaoh Plague, you animate and complicate these issues: are we witness to a revery or a nightmare?

DR: With fiction, in order for it to make sense, I have to somehow understand what I'm reading before the fact, and I believe this is what separates poetry from representation. In my work the visual experience is a foremost concern: the paintings are paintings and they are meant to be looked at. That visual experience is poetic, which is to say the misery or beauty includes the viewer and isn't just a report. Revery or nightmare? Given the choice I'd go with nightmare to be on the safe side, but I hope there isn't too much distance for the beauty not to convulse.

BN: A painting like Titanic, even with that title, is incredibly dreamy, as if whatever is happening in that velvety space is unfolding under so many glittering stars. What's going on here?

DR: This painting primarily grew out of formal interests. I wanted to see what a composition with a unified space would do, compared to compositions with more loosely related elements on different planes. Those usually appear as scratches and tears in a surface barely holding together. I also knew that it would be silver on black, and when I found this image with the tilted deck and frozen figures, I was really struck by an almost comforting sense of resignation. The addition of stars in the distance, or softly falling snow or ash just made sense, and contributed to the silence.

BN: The idea of silence puts me in the mind of a beautiful white-on-white painting you made recently, Void Detached. Obviously a void can be filled, but set loose? Because I don't believe you mean detached in the sense of disinterest. How we reconcile the impossibility of the title with this painting is a matter of negotiating how it was put together and how it was painted. On a purely visual level, if it weren't for the white that blankets the image we might see that it's actually quite densely constructed as well as spatially irrational — an unreal Cubism. We aren't sure what we're seeing, but vision appears to be from all sides at once. How do you see this painting, perhaps as it relates to all your recent work? Because painting seems to be the ghost that you've been after.

DR: This was the first Ghost Painting I completed that wasn't on a black ground. What had previously appeared as a kind of fantastic illumination from behind suddenly resembled the paper-mask source of the image with far greater clarity than anything I'd made before. Going from candle-light to a klieg light glare in one switch. I look at that painting and feel that the forms are loose and could still be shifted, that I could peel it apart. It's very much a stream-of-consciousness composition, and with this sort of work we're more exposed to evidence that the emptiness is real, while at the same time susceptible to the belief that it's not. Even while it appears to be fading away before our eyes.

"Ghost Paintings"

Nov 13 - Dec 23, 2010

Vernissage le 13.11.2010 de 18:00 à 21:00 h

Opening: Saturday 13.11.2010 from 2 to 8 pm

English version. Scroll down for French and Dutch versions

Giving Up the Ghost: A Conversation With David Ratcliff

BN: An apparition, a spectral image of a figure, seems by now central to all your work. The sense that you conjure images that are haunting, and sometimes terrifying, or recur in memory, pervades your practice. Even the earliest, more pop-inflected paintings are like after-images: representations and fragments that are layered and collide to suggest that seeing is not always believing, that sometimes all we have is a trace that is about to vanish into thin air. With these new works, explicitly referred to as Ghost Paintings, once again by means of a particular de-composition, you haunt the image to even greater effect.

DR: The Ghost Paintings started out as a way to bring drawing into the paintings, to move outside of the photographic forms. I had started using, and still often use, photos of drawings from online sources, but at some point I began to re-trace them, or trace the edges of photographic elements with a narrower line. So while they have become fainter, less concrete entities, they've simultaneously bridged the distance my hand has traditionally had from the work. As you said, I haunt the images in a way I'd previously resisted. The tracings are then re-traced with a knife on paper, and it is this knife tracing that is ultimately transferred to the canvas.

BN: I didn't know that you use a knife. In fact, I was going to say that the line in these new paintings reminds me of the cut paper silhouettes of Kara Walker, as well as the slicing of paper "screens" or curtains in the videos of Alex Hubbard. These works are either clearly figurative or abstract, but your paintings are always hybridized, hovering between abstraction and the representation. It's curious to think of your work as related to experimental film, particularly to color and light studies. As befits their overall designation, the paintings do seem dream-like, as if recalled from the unconscious. Who are some of the artists haunting your studio lately?

DR: On my desk right now I've got books and catalogs by Wolfgang Tillmans, Joan Didion, and Sigmar Polke, all of whom trace the layered contours of contemporary society in four dimensions, and all of whom deal with different "ghost" manifestations.

BN: That's an artist who makes photographs, a writer who is one of our keenest observers, and a great alchemist — recently departed. Polke, with whom all your work clearly resonates, is a painter whose sensibility comes to bear much more on a younger generation of American artists than on Europeans, probably because of the convergence of Pop and the psychedelic. But Tillmans, who I admire, isn't someone I associate with your image investigation. And I'm not sure I follow the "four dimensions" remark. Can you talk about that, and about how it is that you are choosing the imagery your work with.

DR: Tillmans's installations are probably the most complete expressions of personal and public life in contemporary society, and I view them similarly to my experience of the internet ... mainly in their astounding combinations of elements that in no way discourages viewer inclusion. He's on par with Joan Didion in how they're both, as you say, keen observers, taking in the world around them over time rather than in an instant. That's another thing I love about Tillmans — how his installations include time in a way that feels important. And of course looming behind it all is "history," which is like a phantom.

Some of the Ghost Paintings are composed using groups of images I'd collected years ago. At the time, I was engaged in very hands-off random searches, and to a degree my image-gathering process has remained deliberately loose because there's no way to anticipate what you come across. Over the past year, I've found myself more drawn to images that tend to highlight the rapidly changing world. Very recent images, as well as those from the past, that contrast with how we want to see things now. I've started using coloring book images from bible stories or from historical events. In coloring-book form, these stories and events tend to empty themselves out and simultaneously open up to a broader spectrum of society. There's something in the simplicity of the outline that I'm drawn to. In searching for images for these new paintings I'm really looking at outlines, at the edges of forms. The interior becomes less important since I'm not even sure it will be made visible. I've used an image from the Vietnam war, for example, a snapshot taken in 1966, of American soldiers posing in front of a group of terrified monks. The soldiers have praying hands and V-for-victory signs, while the monks look really shit-scared. Behind them, a tank has "I'm the god of hell fire!" hand-written on the front.

BN: This is the painting you titled I'm the God of Hell Fire? I don't see almost any of what you're describing.

DR: Right, because in the final painting all you can see is the outline. You can't tell that they're Buddhist monks, and you can't tell that they're American soldiers. They're obviously a group of young men, and they're shirtless, but that's about all that's visible. They're not just from the past. They're gone.

BN: Vietnam makes me think of the painting Swimsuit Napalm. It looks like many images that have been carved and compressed into a single block of milky marble that is somehow melting. The painting is action-packed but elusive, as if the density is an apparition: here, you've converged all-over composition with the monochrome.

DR: Like many people, I tend to experience memory in monochrome. Maybe it's partly my generation, when a lack of color signified the past. Growing up we still had a black-and-white TV in the house. Late night on all the channels, when the programs were finished, there were only color-bars or dense and airy static fuzz. An attraction to the past is something that I need to resist in my work since I'm afraid I'll get it all wrong, but then there is that phantom, that continuum. The paintings tend to look like afterimages of events gone by more than premonitions of events to come. The work you're talking about formally resembles Cubism, but as you said, it's like an apparition, so instead of coming up against hard aggression you enter a more anemic version, as if it's seen through water, or a gravestone rubbing.

BN: At first glance, your work doesn't seem to embody a new form of history painting, and yet it does, certainly in terms of an artist engaged in a "coming to grips" with the presence of the past. In your case, the idea of painting history becomes a recording of something that is happening again: history as a revolving door in which figures and events get jammed up and spun around and ejected. Which is how they appear in the appropriately titled Payday.

DR: Absolutely. Whenever I find myself responding to events from the past it's because I'm responding to them now. If they're not happening currently, in the present day in some form, past events don't really register for me. I don't remember what I just read unless it's got that trigger, that flash of recognition. It might be a by-product of the fact that all the images I use come from online sources, and in shifting through the pool you tend to see the same things over and over again, copies of copies of copies, and with the prevalence of facebook, these repeats are showing up in "real life." Not to say that copies don't work. Payday has it's roots in an eastern-Eurpoean cartoon dealing with immigration and migrant labor. But who is getting paid, and what pay means, is difficult to say when it looks like a massacre.

BN: You might have identified the source of the image as a press photo of a bombing in Iraq, and I wouldn't have any reason not to believe you. Or a bombing image overlaid with figures from a bible story in a coloring-book, which wouldn't be that bizarre, actually, and would offer a perfect example of how you visually articulate feelings that otherwise leave the viewer speechless. Many artists have offered us "the horrors of war" — Thomas Hirschhorn being an obvious recent example — and yet these are almost always mere representations. Your images don't show us how things look so much as how they are absorbed and persist on a visceral and emotional level. I find that the poetics and politics of art overlap in the notion that, as the confessional poet and suicide Anne Sexton once remarked, "Misery from a distance resembles beauty." This coincides with Breton's now-famous declaration: "Beauty will be convulsive or not at all." In a painting like Pharaoh Plague, you animate and complicate these issues: are we witness to a revery or a nightmare?

DR: With fiction, in order for it to make sense, I have to somehow understand what I'm reading before the fact, and I believe this is what separates poetry from representation. In my work the visual experience is a foremost concern: the paintings are paintings and they are meant to be looked at. That visual experience is poetic, which is to say the misery or beauty includes the viewer and isn't just a report. Revery or nightmare? Given the choice I'd go with nightmare to be on the safe side, but I hope there isn't too much distance for the beauty not to convulse.

BN: A painting like Titanic, even with that title, is incredibly dreamy, as if whatever is happening in that velvety space is unfolding under so many glittering stars. What's going on here?

DR: This painting primarily grew out of formal interests. I wanted to see what a composition with a unified space would do, compared to compositions with more loosely related elements on different planes. Those usually appear as scratches and tears in a surface barely holding together. I also knew that it would be silver on black, and when I found this image with the tilted deck and frozen figures, I was really struck by an almost comforting sense of resignation. The addition of stars in the distance, or softly falling snow or ash just made sense, and contributed to the silence.

BN: The idea of silence puts me in the mind of a beautiful white-on-white painting you made recently, Void Detached. Obviously a void can be filled, but set loose? Because I don't believe you mean detached in the sense of disinterest. How we reconcile the impossibility of the title with this painting is a matter of negotiating how it was put together and how it was painted. On a purely visual level, if it weren't for the white that blankets the image we might see that it's actually quite densely constructed as well as spatially irrational — an unreal Cubism. We aren't sure what we're seeing, but vision appears to be from all sides at once. How do you see this painting, perhaps as it relates to all your recent work? Because painting seems to be the ghost that you've been after.

DR: This was the first Ghost Painting I completed that wasn't on a black ground. What had previously appeared as a kind of fantastic illumination from behind suddenly resembled the paper-mask source of the image with far greater clarity than anything I'd made before. Going from candle-light to a klieg light glare in one switch. I look at that painting and feel that the forms are loose and could still be shifted, that I could peel it apart. It's very much a stream-of-consciousness composition, and with this sort of work we're more exposed to evidence that the emptiness is real, while at the same time susceptible to the belief that it's not. Even while it appears to be fading away before our eyes.