Christa Näher

10 Dec 2013 - 08 Feb 2014

CHRISTA NÄHER

El Amor

10 December 2013 - 8 February 2014

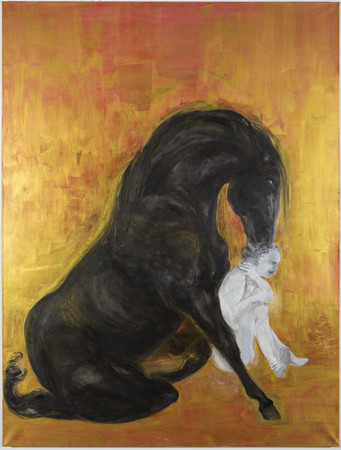

Christa Näher does not merely expect an artwork to disclose itself - she says it should wish to disclose itself. This freedom of art, considered and felt dialogically and implemented with a refusal to take a stranglehold of the work until the very last, requires that great attention be given to relationships. In extended phases in Christa Näher’s work animals have proven as indispensable as mirror images: in the work, these function as open spaces of enquiry. As it turns out, horses in particular did not eventually die away, but manifested themselves time and again, confided in her. She not only associates these with a recurrent genesis but also with regeneration. Näher paints her first horse, „Rotes Pferd“, in 1973. Even when these animals like in the „Schwarze Serie“ („Black series“ 1984) - baretoothed horses in bold strokes - appear to have been thieved from the very teeth of horror, volition as well as transformation are always present. In the wake of the large-sized „Schweinebild“ („Pigs painting“) works developed depicting dark clearly cast spaces and landscapes, black columns, castles under a deep glistening light, as though several notions of time had been displaced or merged into one. This eventually led Christa Näher at the end of the 1980s to the group of works called “Abraum Vorort“, to the archetype of the „Schacht“1 (German for a shaft, that the artist dedicates to a ‘state’) and to the abstract series „Bluthusten salonfähig” (“Coughing Blood Respectably“) which lightly and in luminous ink visualises a movement on paper, namely a movement from the entrails. The titles comprise medical specifications (e.g. “Coughing Blood Respectably No 2 blue-blooded“, „No 4 leuko-variant“, „No 6 vinegar thinned“, „No 1 foxed and dry“) and deal metaphorically also with the artist’s angle on intellectualism. It only becomes apparent with the benefit of hindsight that the spaces - reduced to walls, stairs, chasms and to corridors in which even the movement of breathing in and out has dissipated, or is merely a single and eternal breath - urge for enlivenment and relaxation in order to make the dances of death become merrier. In 1994, Näher exhibits her „Engelordnungen“ in the Trinitatiskirche in Cologne. The superintendent of the church, Kock, starts his preamble with the question „What makes angels dwell in the minds of humans?“ The iconic life-size photo collages with the head of Freddy Mercury are marked by a strong human presence of flesh and blood, yet at the time, as ensouled as they are, were mostly not understood.

Near the end of the 20th century, horses once again are instrumental in leading the painter towards the baroque: at first in figures of equestrian dressage in white-black-grey glazes (amongst which is „Carceri“, 1998, after Piranesi) and in portraits, the names of which stem from the history of ideas and thus localise impulses of the subjects of the paintings: Job, Nero, Vermeuil, Deleuze etc. Näher once quoted Deleuze's sentence „Not everyone is permitted to pose the question of art“. Along with these figures, sensitive, self-forgetful boys enter the work, as does the patient cavalry master of Louis XIII called Antoine de Pluvinel, the travelling thirty year old singer Rudolph who springs from a deeply-felt past, as well as the snow king with tender feelings towards the living, who returns time and again to the horses and roams with them through the ages. Written and oral narrative, encounter and contact increasingly come to the fore. Christa Näher's paintings remain an attempt to look behind memories. If she writes today „to want to remember is a longing for reconciliation“, she is only speaking about an increase in awareness or about the perception of art when one takes this sentence at face value. What she in fact addresses is that recollections of an infinite memory make all reasons turn into one and will dissolve all the antagonisms of time immemorial.

Translated by Raaf van der Sman

1 Wolfgang Winkler has written a text worth reading on the exceptional and impossible nature of the “Schacht” in art, and about how this disconnected ‘state’ is sealed against representation/ reproduction and related to death. Wolfgang Winkler, „Persecution in ‚Schacht’. An essay on Christa Näher’s theoretical epic in pictures On the image as a Master of Death“, in: „Schacht“, Galerie der Stadt Stuttgart (Johann-Karl Schmidt), Ed. Cantz Ostfildern 1991, p. 147-161

El Amor

10 December 2013 - 8 February 2014

Christa Näher does not merely expect an artwork to disclose itself - she says it should wish to disclose itself. This freedom of art, considered and felt dialogically and implemented with a refusal to take a stranglehold of the work until the very last, requires that great attention be given to relationships. In extended phases in Christa Näher’s work animals have proven as indispensable as mirror images: in the work, these function as open spaces of enquiry. As it turns out, horses in particular did not eventually die away, but manifested themselves time and again, confided in her. She not only associates these with a recurrent genesis but also with regeneration. Näher paints her first horse, „Rotes Pferd“, in 1973. Even when these animals like in the „Schwarze Serie“ („Black series“ 1984) - baretoothed horses in bold strokes - appear to have been thieved from the very teeth of horror, volition as well as transformation are always present. In the wake of the large-sized „Schweinebild“ („Pigs painting“) works developed depicting dark clearly cast spaces and landscapes, black columns, castles under a deep glistening light, as though several notions of time had been displaced or merged into one. This eventually led Christa Näher at the end of the 1980s to the group of works called “Abraum Vorort“, to the archetype of the „Schacht“1 (German for a shaft, that the artist dedicates to a ‘state’) and to the abstract series „Bluthusten salonfähig” (“Coughing Blood Respectably“) which lightly and in luminous ink visualises a movement on paper, namely a movement from the entrails. The titles comprise medical specifications (e.g. “Coughing Blood Respectably No 2 blue-blooded“, „No 4 leuko-variant“, „No 6 vinegar thinned“, „No 1 foxed and dry“) and deal metaphorically also with the artist’s angle on intellectualism. It only becomes apparent with the benefit of hindsight that the spaces - reduced to walls, stairs, chasms and to corridors in which even the movement of breathing in and out has dissipated, or is merely a single and eternal breath - urge for enlivenment and relaxation in order to make the dances of death become merrier. In 1994, Näher exhibits her „Engelordnungen“ in the Trinitatiskirche in Cologne. The superintendent of the church, Kock, starts his preamble with the question „What makes angels dwell in the minds of humans?“ The iconic life-size photo collages with the head of Freddy Mercury are marked by a strong human presence of flesh and blood, yet at the time, as ensouled as they are, were mostly not understood.

Near the end of the 20th century, horses once again are instrumental in leading the painter towards the baroque: at first in figures of equestrian dressage in white-black-grey glazes (amongst which is „Carceri“, 1998, after Piranesi) and in portraits, the names of which stem from the history of ideas and thus localise impulses of the subjects of the paintings: Job, Nero, Vermeuil, Deleuze etc. Näher once quoted Deleuze's sentence „Not everyone is permitted to pose the question of art“. Along with these figures, sensitive, self-forgetful boys enter the work, as does the patient cavalry master of Louis XIII called Antoine de Pluvinel, the travelling thirty year old singer Rudolph who springs from a deeply-felt past, as well as the snow king with tender feelings towards the living, who returns time and again to the horses and roams with them through the ages. Written and oral narrative, encounter and contact increasingly come to the fore. Christa Näher's paintings remain an attempt to look behind memories. If she writes today „to want to remember is a longing for reconciliation“, she is only speaking about an increase in awareness or about the perception of art when one takes this sentence at face value. What she in fact addresses is that recollections of an infinite memory make all reasons turn into one and will dissolve all the antagonisms of time immemorial.

Translated by Raaf van der Sman

1 Wolfgang Winkler has written a text worth reading on the exceptional and impossible nature of the “Schacht” in art, and about how this disconnected ‘state’ is sealed against representation/ reproduction and related to death. Wolfgang Winkler, „Persecution in ‚Schacht’. An essay on Christa Näher’s theoretical epic in pictures On the image as a Master of Death“, in: „Schacht“, Galerie der Stadt Stuttgart (Johann-Karl Schmidt), Ed. Cantz Ostfildern 1991, p. 147-161