Art For All

The Color Woodcut In Vienna Around 1900

06 Jul - 03 Oct 2016

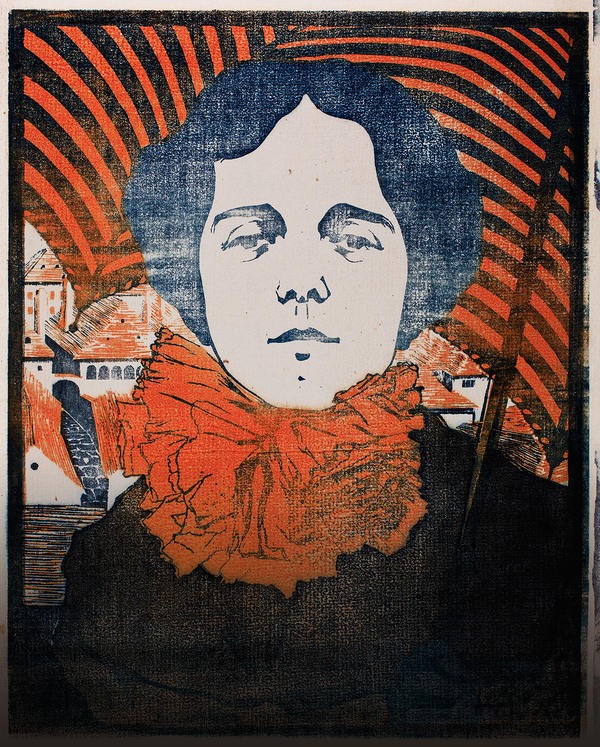

ERWIN LANG, GRETE WIESENTHAL (DAS ROTE MÄDCHEN), UNDATIERT HOLZSCHNITT AUF PAPIER, KOLORIERT, UAK WIEN, KUNSTSAMMLUNG UND ARCHIV / SCHENKUNG O. OBERHUBER

ART FOR ALL

The Color Woodcut In Vienna Around 1900

6 July – 3 October 2016

THE SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT PRESENTS FOR THE FIRST TIME AN OVERVIEW

OF THE COLOR WOODCUT IN VIENNA AT THE BEGINNING OF THE 20TH CENTURY

This exhibition is a first. The woodcut is one of the oldest printing techniques known and reached its zenith during the Middle Ages with Albrecht Dürer. Over the centuries the technique was increasingly forgotten, only to be rediscovered quite suddenly throughout Europe in a trend-setting development at the beginning of the 20th century. This was also the case in Vienna, where numerous artists, including a remarkable number of women, breathed new life into the color woodcut. From July 6 to October 3, 2016 the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt is dedicating a major, long overdue exhibition to this previously largely neglected phenomenon. Some 240 works by over 40 artists – also employing related techniques such as linocut and block printing – give an impressive overview of the subject and demonstrate for the first time the full extent of the aesthetic and social achievements of the color woodcut in Vienna around the turn of the last century. The presentation examines the remarkable enthusiasm with which not only established painters, but also newcomers devoted their attention to the color woodcut during a short but all the more intensive golden age between 1900 and 1910 in Vienna. Among them were members of the Vienna Secession whose names are still familiar today, such as Carl Moll and Emil Orlik, as well as artists who have been almost forgotten like Gustav Marisch, Jutta Sika, Viktor Schufinsky and Marie Uchatius. The latter were all students of the Wiener Kunstgewerbeschule (College of Applied Arts), which was particularly popular among talented young artists. They were fascinated by the technical and formal possibilities of the traditional printing technique, which offered the artistic imagination tremendous freedom. It considerably influenced the emergence of a modern pictorial language at the beginning of the 20th century with its characteristic outline drawings and its stylizsed planar representational style. Moreover, thanks to its affordable prices even for original prints, the color woodcut opened up the previously elitist art market to a broad public. Within the social reformist movement “Kunst für Alle” (Art for All) it encouraged a lively discussion about authenticity and originality on the one hand as well as encouraging artistic creativity beyond the so-called “ivory tower” on the other – topics which have lost nothing of their relevance to this day. The extent to which the color woodcut contributed to a concept of art which aimed to encompass all aspects of life, can be seen in this exhibition. It is assembled in cooperation with the Albertina in Vienna and includes numerous loans from Viennese museums and institutions as well as from estates and private collections.

Dr. Tobias G. Natter, the curator of the exhibition and an expert on Viennese art around 1900, explains: “Although in recent decades Viennese Modernism has been more intensively researched than any other period of Austrian art and cultural history, its contribution to the art of the color woodcut has rarely been discussed. This blind spot can be explained in part against the background of the vast diversity and multifaceted aspects of Viennese Modernism. And it may also be due to the fact that the supreme trinity of that period, Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, have hitherto distorted our view of the medium. None of the three was particularly interested in the woodcut. Nonetheless the rediscovery of the woodcut and associated techniques was an experiment with far-reaching effects during Modernism, not least for successive generations of artists. What is so fascinating about the color woodcut in Vienna is the stylistic and thematic variety as well as the mood of change, which can still be sensed today. It was driven by a wide variety of sources and successfully introduced on behalf of one central topic: the creation of two-dimensional art of lasting value.”

THE COLOR WOODCUT IN VIENNA – HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The golden age of the color woodcut in Vienna around 1900 was decisively influenced not only by the creative milieu, but also by social changes as a whole. This historical context forms the starting point of the exhibition. The nucleus of the rediscovery of the color woodcut lays in the Vienna Secession, a group founded in 1897 by Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Max Kurzweil and others. It soon developed into the most influential association of fine artists in Vienna and represented the new artistic spirit of the age which broke with the backward-looking historicism of the era of the Vienna Ringstrasse. In their famous association building the Secessionists presented highly acclaimed exhibitions, of which three in particular were very important for the color woodcut in Vienna: the VIth. Exhibition (1900) as a witness of the Reception of Japonism which was crucial to the development of the woodcut; the XIVth. Exhibition (1902) with its catalogue of original graphics – woodcuts printed from original plates; and the XXth. Secession Exhibition (1904), which dedicated its own room to the contemporary Viennese woodcut for the first time. A highlight of the exhibition programme in Vienna was the Kunstschau, organised by Klimt and other artists in 1908, in which almost the entire Viennese color woodcut scene was represented. Many of the works on display there are now being presented together in the Schirn

for the first time.

Two magazines were equally important for the establishment of the color woodcut in Vienna. The first was the association journal published by the Secession with the programmatic title Ver Sacrum (Latin for “Sacred Spring”), in which 216 color woodcuts appeared between 1898 and 1903 in a total of six volumes. The second was the Jugendstil magazine Die Fläche (The Plane), which only published two issues, but which assembled numerous color woodcuts and examples of allied techniques such as lino cuts and stencil printing in the second issue in particular.

The publications issued by the Gesellschaft für vervielfältigende Kunst (Society for Duplicating Art) were widely circulated. The society itself was very highly regarded within the framework of the “Art for All” movement, which was gaining in importance at the time. The latter disseminated the view that art should become common property even beyond élite circles and that the distinction between “high art” and the so-called “minor arts” should no longer apply. For many supporters of the popular movement the color woodcut provided an answer to the conflict between modern art, social legitimation and general accessibility. Every year the Society distributed annual portfolios with original graphics among its members. The woodcuts they contained – of which an important example forms part of the Schirn exhibition – were the work in most cases of artists from the Wiener Kunstgewerbeschule (Vienna College of Applied Arts). At the beginning of the 20th century, alongside the Secession, it formed the second centre of Viennese modernism and was very popular among up-and-coming talents because of its pioneer role in the support of a reformed applied arts scene. The school was especially important for women because they were admitted there to study art without restrictions; its graduates included Nora Exner, Nelly Marmorek, Jutta Sika and Marie Uchatius, amongst others. The central focus of the Secessionists, who taught here, especially the professors Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann, was the penetration of all aspects of everyday life with art. In this way they moved close to the increasingly important “Art for All” movement.

A SELECTION OF ARTISTS FEATURED IN THE EXHIBITION

Designed by theatre director Ulrich Rasche, the exhibition circuit displays echoes of Expressionism. In addition to the contemporary historical pre-conditions it also presents the stylistic and thematic variety of the color woodcut in Vienna together with the technical praxis. The tour begins with outstanding examples of Viennese Japonism. Gustav Klimt, for example, collected Asiatica, including several Japanese color woodcuts. In view of the widely endorsed criticism of naturalism, many Secessionists in particular admired the ability of Japanese art to link together art, truth to nature and abstract formal language. This aspect subsequently became very important for the development of the color woodcut in Vienna. The Secessionist artist Emil Orlik (1870–1932), originally a native of Prague, was one of the pioneers. His basic research took him to Japan at an early stage. A key position is occupied by his group of three works The Painter, The Woodcutter and The Printer (all 1901), which are being shown in a separate area in the exhibition in which the technical praxis of the color woodcut is demonstrated. Here the classic production of a Japanese color woodcut with its specialized division of labour for the various stages is demonstrated directly. In Europe, by contrast, the ideal was the “peintre-graveur”, combining the painter, wood engraver and printer in a single individual.

Carl Moser (1873–1939) in particular took up the stimuli Orlik brought back from Japan in an impressive manner. He derived from the Japanese models above all the principle of the “empty space”, which rose to new heights in the color woodcut with its pronounced two-dimensional effect. Examples of the strict division of the picture surface are Moser’s woodcuts White-Spotted Peacock (1905), Breton Child (1904) and Cottage in Brittany (1904). While Japanese art was responsible for imparting the essential design principles to the color woodcut in Vienna, Japanese themes played a negligible role in Vienna. More popular were representations of local landscapes and city views. With his so-called Beethoven Portfolio (from 1902) Carl Moll (1861–1945) created what is today perhaps the most famous series of Viennese woodcuts depicting views. It’s images show the various houses in Vienna in which the composer lived. They were exhibited for the first time at the Kunstschau in 1908. The complete portfolio with its important woodcuts from the Albertina in Vienna will be on view again in the Schirn exhibition.

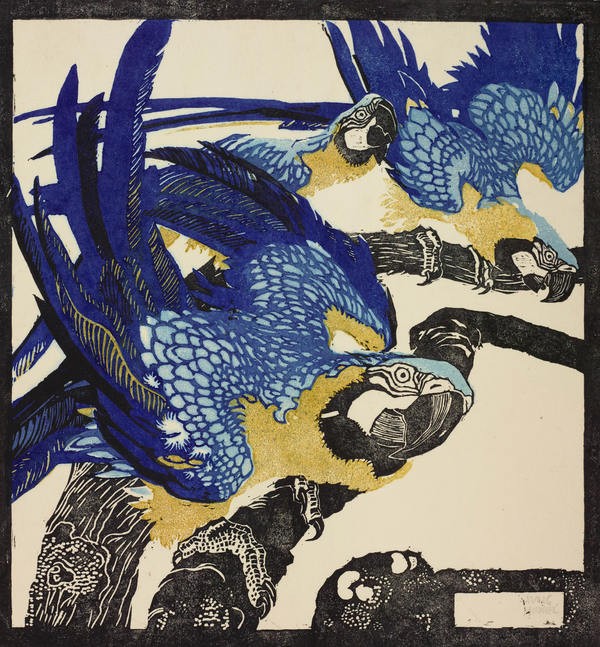

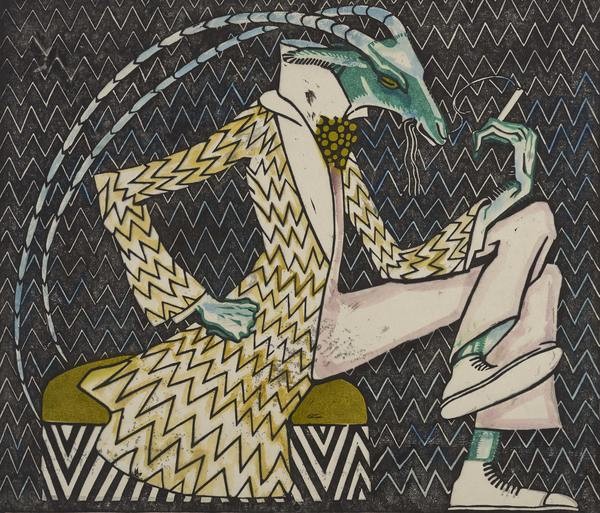

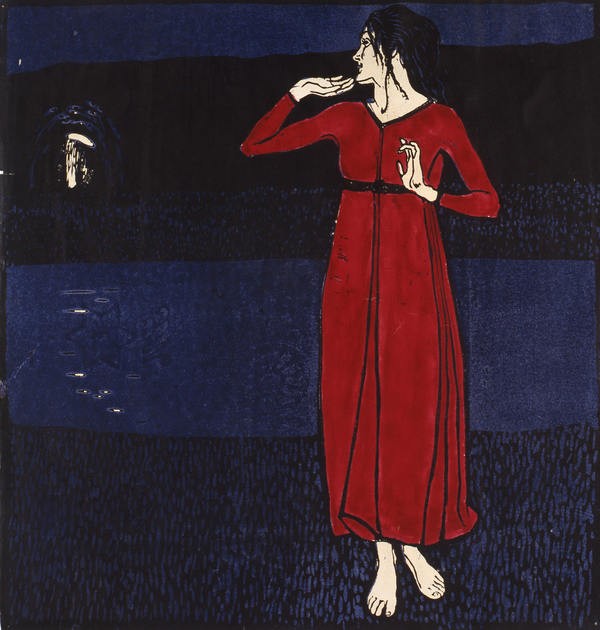

Subjects from the animal kingdom were particularly popular among the artists who worked with the color woodcut. Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel (1881–1965) was the artist who focused most consistently on such animal subjects. On view in the exhibition is his Three Blue Macaws (1909), amongst other works. There is also an example of the work of Marie Uchatius (1882–1958): her Gecko, produced in 1906. Depictions of people are less common than those of animals. Outstanding exceptions include Erwin Lang’s (1886–1962) portrait of the woman who later became his wife, Grete Wiesenthal (ca. 1904) and Carl Anton Reichel’s (1874–1944) impressive series of Studies of Female Nudes (1909), which also herald a new self-image on the part of women.

Rudolf Kalvach (1883–1932) made a contribution to the color woodcut in Vienna which continues to be underestimated to this day. Kalvach commuted regularly between Vienna and the port city of Trieste, which at the time still belonged to Austria-Hungary. His representations of the Port Life in Trieste (1907/08) are among the rare sheets, which show the everyday world of work. Photographer and painter Hugo Henneberg (1863–1918) also portrayed life in Trieste. His woodcuts and linocuts show his heightened sense of water surfaces and reflections, which were a favourite Art Nouveau theme. An impressive example of this is Henneberg’s Blue Pond (ca. 1904) with its filigree ribbons, eddies and arcs, which is also displayed in the Schirn.

Viennese art around 1900 maintained a special passion for the grotesque. This could be seen from an early date in the color woodcut, for example the sheet Circus Parade (ca. 1906/07) by an unknown artist of the Wiener Werkstätte. Also on view in the exhibition is Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel’s Smoking Cricket (1910), which points forward to the Art Deco trends of the 1920s. The latest work in the exhibition chronologically speaking is by Viktor Schufinsky (1876–1947), who was famous for his grotesque ideas. His work Swordsmen looks like an anticipation of the modern world of pixels. The graphic work was created in 1914 and thus stands at the end of the golden age of the color woodcut in Vienna.

A separate chapter, which marks the end of the tour of the exhibition, is dedicated to the presentation of associated techniques, whose results are often difficult to distinguish from those of the woodcut. In addition to the linocut, important examples of the stencil cut, such as Marie Uchatius’s Panther – Pattern for Endpapers (ca. 1905), spray technique and the papercut technique developed by Franz von Zülow (1883–1963) are also presented.

An exhibition of the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt in cooperation with the Albertina, Vienna.

The Color Woodcut In Vienna Around 1900

6 July – 3 October 2016

THE SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT PRESENTS FOR THE FIRST TIME AN OVERVIEW

OF THE COLOR WOODCUT IN VIENNA AT THE BEGINNING OF THE 20TH CENTURY

This exhibition is a first. The woodcut is one of the oldest printing techniques known and reached its zenith during the Middle Ages with Albrecht Dürer. Over the centuries the technique was increasingly forgotten, only to be rediscovered quite suddenly throughout Europe in a trend-setting development at the beginning of the 20th century. This was also the case in Vienna, where numerous artists, including a remarkable number of women, breathed new life into the color woodcut. From July 6 to October 3, 2016 the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt is dedicating a major, long overdue exhibition to this previously largely neglected phenomenon. Some 240 works by over 40 artists – also employing related techniques such as linocut and block printing – give an impressive overview of the subject and demonstrate for the first time the full extent of the aesthetic and social achievements of the color woodcut in Vienna around the turn of the last century. The presentation examines the remarkable enthusiasm with which not only established painters, but also newcomers devoted their attention to the color woodcut during a short but all the more intensive golden age between 1900 and 1910 in Vienna. Among them were members of the Vienna Secession whose names are still familiar today, such as Carl Moll and Emil Orlik, as well as artists who have been almost forgotten like Gustav Marisch, Jutta Sika, Viktor Schufinsky and Marie Uchatius. The latter were all students of the Wiener Kunstgewerbeschule (College of Applied Arts), which was particularly popular among talented young artists. They were fascinated by the technical and formal possibilities of the traditional printing technique, which offered the artistic imagination tremendous freedom. It considerably influenced the emergence of a modern pictorial language at the beginning of the 20th century with its characteristic outline drawings and its stylizsed planar representational style. Moreover, thanks to its affordable prices even for original prints, the color woodcut opened up the previously elitist art market to a broad public. Within the social reformist movement “Kunst für Alle” (Art for All) it encouraged a lively discussion about authenticity and originality on the one hand as well as encouraging artistic creativity beyond the so-called “ivory tower” on the other – topics which have lost nothing of their relevance to this day. The extent to which the color woodcut contributed to a concept of art which aimed to encompass all aspects of life, can be seen in this exhibition. It is assembled in cooperation with the Albertina in Vienna and includes numerous loans from Viennese museums and institutions as well as from estates and private collections.

Dr. Tobias G. Natter, the curator of the exhibition and an expert on Viennese art around 1900, explains: “Although in recent decades Viennese Modernism has been more intensively researched than any other period of Austrian art and cultural history, its contribution to the art of the color woodcut has rarely been discussed. This blind spot can be explained in part against the background of the vast diversity and multifaceted aspects of Viennese Modernism. And it may also be due to the fact that the supreme trinity of that period, Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, have hitherto distorted our view of the medium. None of the three was particularly interested in the woodcut. Nonetheless the rediscovery of the woodcut and associated techniques was an experiment with far-reaching effects during Modernism, not least for successive generations of artists. What is so fascinating about the color woodcut in Vienna is the stylistic and thematic variety as well as the mood of change, which can still be sensed today. It was driven by a wide variety of sources and successfully introduced on behalf of one central topic: the creation of two-dimensional art of lasting value.”

THE COLOR WOODCUT IN VIENNA – HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The golden age of the color woodcut in Vienna around 1900 was decisively influenced not only by the creative milieu, but also by social changes as a whole. This historical context forms the starting point of the exhibition. The nucleus of the rediscovery of the color woodcut lays in the Vienna Secession, a group founded in 1897 by Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Max Kurzweil and others. It soon developed into the most influential association of fine artists in Vienna and represented the new artistic spirit of the age which broke with the backward-looking historicism of the era of the Vienna Ringstrasse. In their famous association building the Secessionists presented highly acclaimed exhibitions, of which three in particular were very important for the color woodcut in Vienna: the VIth. Exhibition (1900) as a witness of the Reception of Japonism which was crucial to the development of the woodcut; the XIVth. Exhibition (1902) with its catalogue of original graphics – woodcuts printed from original plates; and the XXth. Secession Exhibition (1904), which dedicated its own room to the contemporary Viennese woodcut for the first time. A highlight of the exhibition programme in Vienna was the Kunstschau, organised by Klimt and other artists in 1908, in which almost the entire Viennese color woodcut scene was represented. Many of the works on display there are now being presented together in the Schirn

for the first time.

Two magazines were equally important for the establishment of the color woodcut in Vienna. The first was the association journal published by the Secession with the programmatic title Ver Sacrum (Latin for “Sacred Spring”), in which 216 color woodcuts appeared between 1898 and 1903 in a total of six volumes. The second was the Jugendstil magazine Die Fläche (The Plane), which only published two issues, but which assembled numerous color woodcuts and examples of allied techniques such as lino cuts and stencil printing in the second issue in particular.

The publications issued by the Gesellschaft für vervielfältigende Kunst (Society for Duplicating Art) were widely circulated. The society itself was very highly regarded within the framework of the “Art for All” movement, which was gaining in importance at the time. The latter disseminated the view that art should become common property even beyond élite circles and that the distinction between “high art” and the so-called “minor arts” should no longer apply. For many supporters of the popular movement the color woodcut provided an answer to the conflict between modern art, social legitimation and general accessibility. Every year the Society distributed annual portfolios with original graphics among its members. The woodcuts they contained – of which an important example forms part of the Schirn exhibition – were the work in most cases of artists from the Wiener Kunstgewerbeschule (Vienna College of Applied Arts). At the beginning of the 20th century, alongside the Secession, it formed the second centre of Viennese modernism and was very popular among up-and-coming talents because of its pioneer role in the support of a reformed applied arts scene. The school was especially important for women because they were admitted there to study art without restrictions; its graduates included Nora Exner, Nelly Marmorek, Jutta Sika and Marie Uchatius, amongst others. The central focus of the Secessionists, who taught here, especially the professors Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann, was the penetration of all aspects of everyday life with art. In this way they moved close to the increasingly important “Art for All” movement.

A SELECTION OF ARTISTS FEATURED IN THE EXHIBITION

Designed by theatre director Ulrich Rasche, the exhibition circuit displays echoes of Expressionism. In addition to the contemporary historical pre-conditions it also presents the stylistic and thematic variety of the color woodcut in Vienna together with the technical praxis. The tour begins with outstanding examples of Viennese Japonism. Gustav Klimt, for example, collected Asiatica, including several Japanese color woodcuts. In view of the widely endorsed criticism of naturalism, many Secessionists in particular admired the ability of Japanese art to link together art, truth to nature and abstract formal language. This aspect subsequently became very important for the development of the color woodcut in Vienna. The Secessionist artist Emil Orlik (1870–1932), originally a native of Prague, was one of the pioneers. His basic research took him to Japan at an early stage. A key position is occupied by his group of three works The Painter, The Woodcutter and The Printer (all 1901), which are being shown in a separate area in the exhibition in which the technical praxis of the color woodcut is demonstrated. Here the classic production of a Japanese color woodcut with its specialized division of labour for the various stages is demonstrated directly. In Europe, by contrast, the ideal was the “peintre-graveur”, combining the painter, wood engraver and printer in a single individual.

Carl Moser (1873–1939) in particular took up the stimuli Orlik brought back from Japan in an impressive manner. He derived from the Japanese models above all the principle of the “empty space”, which rose to new heights in the color woodcut with its pronounced two-dimensional effect. Examples of the strict division of the picture surface are Moser’s woodcuts White-Spotted Peacock (1905), Breton Child (1904) and Cottage in Brittany (1904). While Japanese art was responsible for imparting the essential design principles to the color woodcut in Vienna, Japanese themes played a negligible role in Vienna. More popular were representations of local landscapes and city views. With his so-called Beethoven Portfolio (from 1902) Carl Moll (1861–1945) created what is today perhaps the most famous series of Viennese woodcuts depicting views. It’s images show the various houses in Vienna in which the composer lived. They were exhibited for the first time at the Kunstschau in 1908. The complete portfolio with its important woodcuts from the Albertina in Vienna will be on view again in the Schirn exhibition.

Subjects from the animal kingdom were particularly popular among the artists who worked with the color woodcut. Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel (1881–1965) was the artist who focused most consistently on such animal subjects. On view in the exhibition is his Three Blue Macaws (1909), amongst other works. There is also an example of the work of Marie Uchatius (1882–1958): her Gecko, produced in 1906. Depictions of people are less common than those of animals. Outstanding exceptions include Erwin Lang’s (1886–1962) portrait of the woman who later became his wife, Grete Wiesenthal (ca. 1904) and Carl Anton Reichel’s (1874–1944) impressive series of Studies of Female Nudes (1909), which also herald a new self-image on the part of women.

Rudolf Kalvach (1883–1932) made a contribution to the color woodcut in Vienna which continues to be underestimated to this day. Kalvach commuted regularly between Vienna and the port city of Trieste, which at the time still belonged to Austria-Hungary. His representations of the Port Life in Trieste (1907/08) are among the rare sheets, which show the everyday world of work. Photographer and painter Hugo Henneberg (1863–1918) also portrayed life in Trieste. His woodcuts and linocuts show his heightened sense of water surfaces and reflections, which were a favourite Art Nouveau theme. An impressive example of this is Henneberg’s Blue Pond (ca. 1904) with its filigree ribbons, eddies and arcs, which is also displayed in the Schirn.

Viennese art around 1900 maintained a special passion for the grotesque. This could be seen from an early date in the color woodcut, for example the sheet Circus Parade (ca. 1906/07) by an unknown artist of the Wiener Werkstätte. Also on view in the exhibition is Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel’s Smoking Cricket (1910), which points forward to the Art Deco trends of the 1920s. The latest work in the exhibition chronologically speaking is by Viktor Schufinsky (1876–1947), who was famous for his grotesque ideas. His work Swordsmen looks like an anticipation of the modern world of pixels. The graphic work was created in 1914 and thus stands at the end of the golden age of the color woodcut in Vienna.

A separate chapter, which marks the end of the tour of the exhibition, is dedicated to the presentation of associated techniques, whose results are often difficult to distinguish from those of the woodcut. In addition to the linocut, important examples of the stencil cut, such as Marie Uchatius’s Panther – Pattern for Endpapers (ca. 1905), spray technique and the papercut technique developed by Franz von Zülow (1883–1963) are also presented.

An exhibition of the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt in cooperation with the Albertina, Vienna.