132,54 m²

24 Jan - 04 Apr 2015

132,54 m2

24 January 2015 - 4 April 2015

The group show “132.54 m2” at SCHLEICHER/LANGE will include works by artists A KASSEN, Vladimir Houdek, Hervé Humbert, Krištof Kintera, Maria Loboda and Diogo Pimentão.

The use of everyday objects as the basis of artworks has long since held a firm place in art history. Instilling such “objets trouvé” with meanings and creating new contexts of signification is part of the relevant artistic practice. “132.54 m2” presents works by di erent artists who each in their own way resort to such strategies: The works rely on objects from interiors or toy with the latter’s appearance, such that at first sight the gallery space resembles a living room of sorts. Beneath the visible surface of these artworks you can then discover further, hidden levels of meaning. Viewers are invited to participate in this game of the intellect and explore the respective meanings. In this context, the works are like doors that viewers can open.

Kristof Kintera’s sculpture “Resurrection III” consists of a carpet stood on one end. Kintera often makes use of everyday objects that sharply deviate from what viewers are accustomed to seeing. Depending on the emphasis, his works include humorous or threatening nuances, or a touch of social critique.

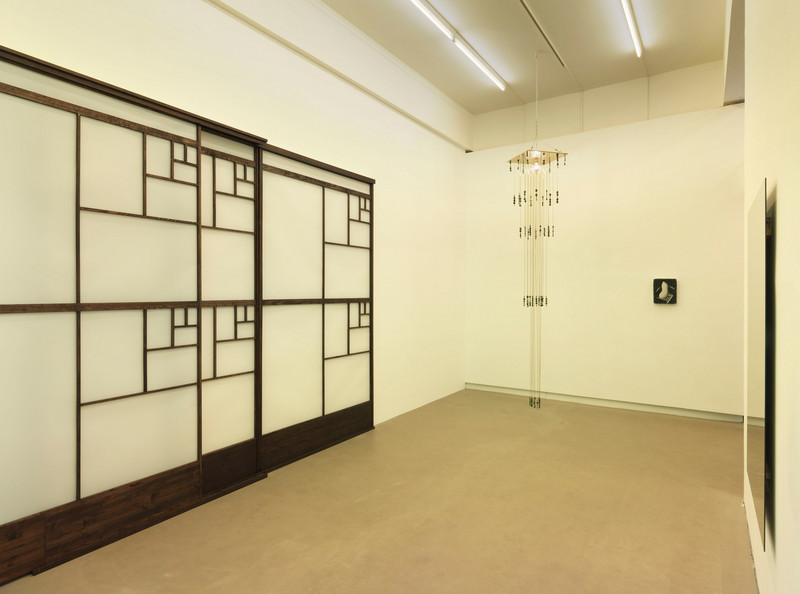

Maria Loboda’s piece “The Sentence In Its Temporary Form As Turquoise And Quartz” is reminiscent of a fin-de-siècle luminaire, bringing to mind both the style then and decadence. The elements used to construct it are combined according to a specific pattern, namely Bacon’s cipher. This binary code replaces the letters of the alphabet in sets of five letters using two com-ponents, in this case quartzes and turquoises. A set of five quartzes or turquoises reflects a letter in the work’s title. In this way, each individual word in the title forms part of the work.

Hervé Humbert’s “Madame (Detail)” is a mirror from a former bordello in Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg district. In its function as a mirror it constantly produces images and superimposes them one over the next, images that are not enduring and leave no visible traces. Although the mirror images dissipate and thus become invisible (e.g., because visitors move on or the place where it is hung is changed) they have become inscribed in it. In other words, the mirror tells of images without actually showing them. Thanks to its special history, the images are especially vivid.

Hervé Humbert’s “DIN” is an installation consisting of three large identical panels made of dark wood and translucent film. Each is subdivided into ever smaller rectangles. The geometrical subdivision transfers the DIN paper format norm qua two-dimensional scheme onto three dimen-sions in the form of an object. “DIN” alludes to how strongly we are surrounded by norms today. Moreover, the piece functions as a room divider and reflects how strongly the norms intrude into our lifeworld today, including our private homes. By virtue of being staged as a mobile room divider, the work also brings to mind interior elements to be encountered in the Asian architec-tural context.

“The Colour Of Things (Carpet)” by artist group A KASSEN explores the representation of things by photographing objects (in this case a carpet) and then pulverising them. The photo of the intact carpet is placed alongside the dust of the shredded object. The carpet per se is not repre-sented, but only two artistic aggregate states of it: the photo and the small fibres. The viewer has to recreate the original object qua carpet from the external appearance as suggested by the photo and its properties as fibres.

Maria Loboda’s “The Totality Of Everything That Exists (Error)” consists of bright turquoise paint and is based on computations by Karl Glazebrook and Ivan Baldry made in 2001. They conducted a spectral analysis of the light of over 200,000 galaxies and calculated the median colour value in order to pinpoint the colour of the universe. Unfortunately while the computation was running there was a glitch in the software, leading to the shade calculated “Cosmic Turquoise” being wrong – one year later they rectified the value to a beige-white. Loboda’s work enables us to reproduce the correct and the incorrect colour of the universe whenever and wherever we like.

Hervé Humbert’s “Untitled” strongly defines the rear gallery space. The sculpture, which you can enter, is sized 3 x 3 metres and derives from a 1950s luminaire design by Greta Magnusson Gross-mann. It consists of 20 panels that can in part be opened or closed. The colour used for some of the elements derives from a colour scale Le Corbusier compiled and which Humbert came across at the Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart. Humbert feels reconstruction is not an act of copying but of comprehending the world, similar to photography but simply using objects.

Humbert has conceived his piece as an autonomous space within the space as an outsized enlargement of the Swedish design classic. On the one hand, it forms the heart of the exhibition, on the other a place to which visitors can withdraw and experience an intimate sense of space.

The gallery walls display works chosen for the fact that they relate to interior objects above all because artworks in private spaces are always part of home living in that the owners quite liter-ally live with them. In other words, here the aspect of a use function as the other pieces also express, recedes into the background.

Diogo Pimentão’s drawings are to be viewed on the wall in the rear space, and clearly go far beyond the usual notion of drawing. They are paper and graphite works that frequently leave two dimensions behind them and intervene to a more or less pronounced extent in three-dimensional space, often indeed morphing into standalone sculptures. The transgressions in the exhibitions are thus not just spatial or between (everyday) object, installation and sculpture, but also between genres. Moreover, Pimentão often applies the graphite so thickly that the material itself is transformed and the paper seems, for example, actually to be metal.

Vladimir Houdek’s paintings extend the painterly medium to include a collage-like element by incorporating paper particles into the oils. The layer upon layer of thick paint gives rise to haptic paintings, an aspect consciously emphasised by deliberate damage done to the surface and thus inaccuracies introduced into the respective textures. He deconstructs the incorporated paper elements by replacing defining sections such as heads, faces, eyes, etc. by painted geometrical shapes. These have a magnetic quality, and in part a grotesque, not to say malicious e ect, something underscored by the fact that the transmuted bodies float in space.

Text: Kirsten Eggers (2015)

Translation: Dr. Jeremy Gaines

24 January 2015 - 4 April 2015

The group show “132.54 m2” at SCHLEICHER/LANGE will include works by artists A KASSEN, Vladimir Houdek, Hervé Humbert, Krištof Kintera, Maria Loboda and Diogo Pimentão.

The use of everyday objects as the basis of artworks has long since held a firm place in art history. Instilling such “objets trouvé” with meanings and creating new contexts of signification is part of the relevant artistic practice. “132.54 m2” presents works by di erent artists who each in their own way resort to such strategies: The works rely on objects from interiors or toy with the latter’s appearance, such that at first sight the gallery space resembles a living room of sorts. Beneath the visible surface of these artworks you can then discover further, hidden levels of meaning. Viewers are invited to participate in this game of the intellect and explore the respective meanings. In this context, the works are like doors that viewers can open.

Kristof Kintera’s sculpture “Resurrection III” consists of a carpet stood on one end. Kintera often makes use of everyday objects that sharply deviate from what viewers are accustomed to seeing. Depending on the emphasis, his works include humorous or threatening nuances, or a touch of social critique.

Maria Loboda’s piece “The Sentence In Its Temporary Form As Turquoise And Quartz” is reminiscent of a fin-de-siècle luminaire, bringing to mind both the style then and decadence. The elements used to construct it are combined according to a specific pattern, namely Bacon’s cipher. This binary code replaces the letters of the alphabet in sets of five letters using two com-ponents, in this case quartzes and turquoises. A set of five quartzes or turquoises reflects a letter in the work’s title. In this way, each individual word in the title forms part of the work.

Hervé Humbert’s “Madame (Detail)” is a mirror from a former bordello in Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg district. In its function as a mirror it constantly produces images and superimposes them one over the next, images that are not enduring and leave no visible traces. Although the mirror images dissipate and thus become invisible (e.g., because visitors move on or the place where it is hung is changed) they have become inscribed in it. In other words, the mirror tells of images without actually showing them. Thanks to its special history, the images are especially vivid.

Hervé Humbert’s “DIN” is an installation consisting of three large identical panels made of dark wood and translucent film. Each is subdivided into ever smaller rectangles. The geometrical subdivision transfers the DIN paper format norm qua two-dimensional scheme onto three dimen-sions in the form of an object. “DIN” alludes to how strongly we are surrounded by norms today. Moreover, the piece functions as a room divider and reflects how strongly the norms intrude into our lifeworld today, including our private homes. By virtue of being staged as a mobile room divider, the work also brings to mind interior elements to be encountered in the Asian architec-tural context.

“The Colour Of Things (Carpet)” by artist group A KASSEN explores the representation of things by photographing objects (in this case a carpet) and then pulverising them. The photo of the intact carpet is placed alongside the dust of the shredded object. The carpet per se is not repre-sented, but only two artistic aggregate states of it: the photo and the small fibres. The viewer has to recreate the original object qua carpet from the external appearance as suggested by the photo and its properties as fibres.

Maria Loboda’s “The Totality Of Everything That Exists (Error)” consists of bright turquoise paint and is based on computations by Karl Glazebrook and Ivan Baldry made in 2001. They conducted a spectral analysis of the light of over 200,000 galaxies and calculated the median colour value in order to pinpoint the colour of the universe. Unfortunately while the computation was running there was a glitch in the software, leading to the shade calculated “Cosmic Turquoise” being wrong – one year later they rectified the value to a beige-white. Loboda’s work enables us to reproduce the correct and the incorrect colour of the universe whenever and wherever we like.

Hervé Humbert’s “Untitled” strongly defines the rear gallery space. The sculpture, which you can enter, is sized 3 x 3 metres and derives from a 1950s luminaire design by Greta Magnusson Gross-mann. It consists of 20 panels that can in part be opened or closed. The colour used for some of the elements derives from a colour scale Le Corbusier compiled and which Humbert came across at the Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart. Humbert feels reconstruction is not an act of copying but of comprehending the world, similar to photography but simply using objects.

Humbert has conceived his piece as an autonomous space within the space as an outsized enlargement of the Swedish design classic. On the one hand, it forms the heart of the exhibition, on the other a place to which visitors can withdraw and experience an intimate sense of space.

The gallery walls display works chosen for the fact that they relate to interior objects above all because artworks in private spaces are always part of home living in that the owners quite liter-ally live with them. In other words, here the aspect of a use function as the other pieces also express, recedes into the background.

Diogo Pimentão’s drawings are to be viewed on the wall in the rear space, and clearly go far beyond the usual notion of drawing. They are paper and graphite works that frequently leave two dimensions behind them and intervene to a more or less pronounced extent in three-dimensional space, often indeed morphing into standalone sculptures. The transgressions in the exhibitions are thus not just spatial or between (everyday) object, installation and sculpture, but also between genres. Moreover, Pimentão often applies the graphite so thickly that the material itself is transformed and the paper seems, for example, actually to be metal.

Vladimir Houdek’s paintings extend the painterly medium to include a collage-like element by incorporating paper particles into the oils. The layer upon layer of thick paint gives rise to haptic paintings, an aspect consciously emphasised by deliberate damage done to the surface and thus inaccuracies introduced into the respective textures. He deconstructs the incorporated paper elements by replacing defining sections such as heads, faces, eyes, etc. by painted geometrical shapes. These have a magnetic quality, and in part a grotesque, not to say malicious e ect, something underscored by the fact that the transmuted bodies float in space.

Text: Kirsten Eggers (2015)

Translation: Dr. Jeremy Gaines