Alison Moffett

21 Mar - 02 May 2009

© Alison Moffett, courtesy galerie schleicher+lange, Paris

from the series 'sites' (2009), pencil and collage elements on paper, framed, 40 x 30 cm

from the series 'sites' (2009), pencil and collage elements on paper, framed, 40 x 30 cm

© Alison Moffett, courtesy galerie schleicher+lange, Paris

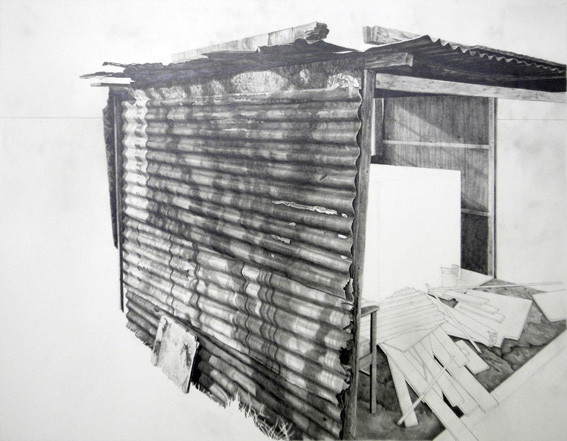

'Quarantine I', 2008, pencil and collage elements on paper, framed, 225 cm x 297,5 cm

'Quarantine I', 2008, pencil and collage elements on paper, framed, 225 cm x 297,5 cm

© Alison Moffett, courtesy galerie schleicher+lange, Paris

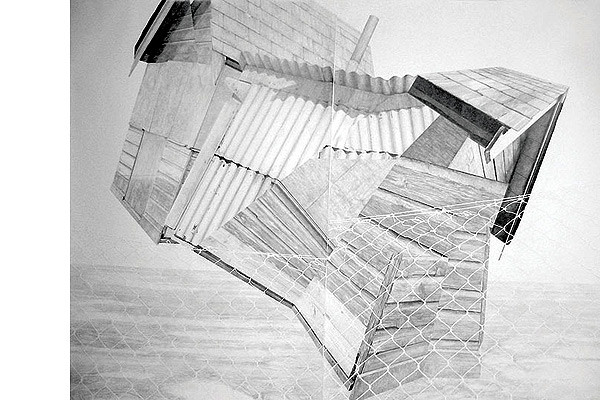

'Quarantine I', 2008, pencil and collage elements on paper, framed, 225 x 280 cm

'Quarantine I', 2008, pencil and collage elements on paper, framed, 225 x 280 cm

Alison Moffett: grey

Alison Moffett’s drawings are usually on a 1:1 scale, as if she were trying to create an antagonism between the respective spaces of the work and the spectator. This friction is reinforced by the themes she tackles: refined architectural forms are set against makeshift housing, such as sheds. The spectator is torn between an idealised space and a living space.

'Quarantine 1' and 'Quarantine 2', two of the works presented by the artist at this, her second, solo exhibition at the gallery are an example of this juxtaposition. Her large-scale drawings play on the contrast between standard modernist architecture, from shopping centre to bus shelter, and the most rudimentary of shelters. As her work moves in this new direction, the artist alludes to science, exploration and space, and fiction.

These different dimensions underpin each drawing, in which perspectives are superimposed or draft film and collage elements disturb the immaculate lines of a virtuosic stroke. Apparently divergent topographies are the backdrop for a number of utopian living spaces. On the one hand, they refer to the quest for that perfect architectural well-being already discernible in “Eco House” and the villas of Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, I.M. Pei and Peter Blake portrayed in “Moon Drawings”. On the other hand, science supports the dream of extraordinary places, far-flung and full of surprises, at odds with the lunar landscapes. Finally, the notion of precarious shelter calls to mind such authors as Henri David Thoreau, who sang the praises of the basic abode.

The perfection of the lines, the skilfully applied layers of graphite, the dreamlike spaces created from scratch could leave us gently drifting in the realm of fantasy. But an uneasiness seeps in as a result of the absence of humans or vegetation. It arrives surreptitiously via this acute figurative precision that underscores as much the beauty of the shapes as the wearing away of the construction materials, including the graphite in which the image is rendered.

In the two series of drawings exhibited, we get into the detail of this uneasiness. The drawings are small and intimate. Rather than being confronted by them, spectators have to approach the pieces. In the “Sites” series, a white cube is secreted in a shed, like an inversion of the space of contemporary art, rendered opaque and impenetrable. The notion of the ideal also impinges on the world of contemporary art, in particular the neutral and staged environment in which we perceive works of art. Like a reversal of the black monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, this white cube is at the centre of the patchwork of improvised materials, absorbing the life force of its surroundings, in the same way that dreams sometimes encroach upon reality.

The other series of drawings depicts wooden blocks which form compositions in an empty space. They replicate the possible layout of blocks of flats. This more abstract series represents the structural gesture, the urge to compose an abstract space despite its being intended for habitation.

A set of sculptures created with Chris Cornish completes the exhibition, taking it to its extreme. Perspex boxes contain chicken wire (frequently used by the artist in her drawings) that echo the surface of the planet Mars in 3-D. Mars is as much the subject of sophisticated scientific research as of the most ambitious science-fiction productions. Furthermore, chicken wire, often used to make rather rudimentary fences, has a similar structure to graphene, a two-dimensional crystal, several sheets of which stacked together make graphite. Alison Moffett is intrigued by the composition of the material with which she works, seeing in it a juxtaposition comparable to that of an ancient matter and an ultra-contemporary structure, which is currently of great interest in scientific fields (in particular nanoelectronics). Hence the reduced scale of her more recent drawings and her interest in a space for projection and the scientific dream.

Alison Moffett’s drawings are usually on a 1:1 scale, as if she were trying to create an antagonism between the respective spaces of the work and the spectator. This friction is reinforced by the themes she tackles: refined architectural forms are set against makeshift housing, such as sheds. The spectator is torn between an idealised space and a living space.

'Quarantine 1' and 'Quarantine 2', two of the works presented by the artist at this, her second, solo exhibition at the gallery are an example of this juxtaposition. Her large-scale drawings play on the contrast between standard modernist architecture, from shopping centre to bus shelter, and the most rudimentary of shelters. As her work moves in this new direction, the artist alludes to science, exploration and space, and fiction.

These different dimensions underpin each drawing, in which perspectives are superimposed or draft film and collage elements disturb the immaculate lines of a virtuosic stroke. Apparently divergent topographies are the backdrop for a number of utopian living spaces. On the one hand, they refer to the quest for that perfect architectural well-being already discernible in “Eco House” and the villas of Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, I.M. Pei and Peter Blake portrayed in “Moon Drawings”. On the other hand, science supports the dream of extraordinary places, far-flung and full of surprises, at odds with the lunar landscapes. Finally, the notion of precarious shelter calls to mind such authors as Henri David Thoreau, who sang the praises of the basic abode.

The perfection of the lines, the skilfully applied layers of graphite, the dreamlike spaces created from scratch could leave us gently drifting in the realm of fantasy. But an uneasiness seeps in as a result of the absence of humans or vegetation. It arrives surreptitiously via this acute figurative precision that underscores as much the beauty of the shapes as the wearing away of the construction materials, including the graphite in which the image is rendered.

In the two series of drawings exhibited, we get into the detail of this uneasiness. The drawings are small and intimate. Rather than being confronted by them, spectators have to approach the pieces. In the “Sites” series, a white cube is secreted in a shed, like an inversion of the space of contemporary art, rendered opaque and impenetrable. The notion of the ideal also impinges on the world of contemporary art, in particular the neutral and staged environment in which we perceive works of art. Like a reversal of the black monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, this white cube is at the centre of the patchwork of improvised materials, absorbing the life force of its surroundings, in the same way that dreams sometimes encroach upon reality.

The other series of drawings depicts wooden blocks which form compositions in an empty space. They replicate the possible layout of blocks of flats. This more abstract series represents the structural gesture, the urge to compose an abstract space despite its being intended for habitation.

A set of sculptures created with Chris Cornish completes the exhibition, taking it to its extreme. Perspex boxes contain chicken wire (frequently used by the artist in her drawings) that echo the surface of the planet Mars in 3-D. Mars is as much the subject of sophisticated scientific research as of the most ambitious science-fiction productions. Furthermore, chicken wire, often used to make rather rudimentary fences, has a similar structure to graphene, a two-dimensional crystal, several sheets of which stacked together make graphite. Alison Moffett is intrigued by the composition of the material with which she works, seeing in it a juxtaposition comparable to that of an ancient matter and an ultra-contemporary structure, which is currently of great interest in scientific fields (in particular nanoelectronics). Hence the reduced scale of her more recent drawings and her interest in a space for projection and the scientific dream.