Christine Sun Kim

Cues on Point

17 Feb - 16 Apr 2023

Christine Sun Kim, Cues on Point, installation view, Secession 2023, photo: Oliver Ottenschläger. Courtesy of the artist, Secession and François Ghebaly Gallery.

Christine Sun Kim, Cues on Point, installation view, Secession 2023, photo: Oliver Ottenschläger. Courtesy of the artist, Secession and François Ghebaly Gallery.

Christine Sun Kim, Cues on Point, installation view, Secession 2023, photo: Oliver Ottenschläger. Courtesy of the artist, Secession and François Ghebaly Gallery.

Christine Sun Kim, Cues on Point, installation view, Secession 2023, photo: Oliver Ottenschläger. Courtesy of the artist, Secession and François Ghebaly Gallery.

Christine Sun Kim, Cues on Point, installation view, Secession 2023, photo: Oliver Ottenschläger. Courtesy of the artist, Secession and François Ghebaly Gallery.

Christine Sun Kim, Cues on Point, installation view, Secession 2023, photo: Oliver Ottenschläger. Courtesy of the artist, Secession and François Ghebaly Gallery.

Christine Sun Kim, Cues on Point, installation view, Secession 2023, photo: Oliver Ottenschläger. Courtesy of the artist, Secession and François Ghebaly Gallery.

Christine Sun Kim, Cues on Point, installation view, Secession 2023, photo: Oliver Ottenschläger. Courtesy of the artist, Secession and François Ghebaly Gallery.

Christine Sun Kim, Cues on Point, installation view, Secession 2023, photo: Oliver Ottenschläger. Courtesy of the artist, Secession and François Ghebaly Gallery.

Christine Sun Kim’s art brims with rhythm and dynamic energy. Small-format drawings and sprawling murals, internet memes, text messages in public spaces, and banners towed across the sky by airplanes pack a punch and seem to want to explode the confines and constraints of their media. Her drawings are graphical and spare and largely fall into one of two categories: one utilizes the aesthetics of infographics, while the other adopts the formal repertoire of comic strips, notably speed lines to convey action and reaction.

Language, sound, body, identity and diaspora, translation, hierarchization, principles of exclusion, and societal norms: these are some of the vital concerns to which the artist dedicates herself in her formally diverse output. Many of her works share with the audience how it feels to be structurally and systematically excluded from the hearing majority community; to be forever subject to the rules of others and have to fight for opportunities that are available by default to the hearing. Kim’s art is unmistakably political, at its core demanding greater visibility for Deaf people* and wider recognition of disability access writ large.

Sign language is a constant theme on the formal and aesthetic level as well as the level of content. In recent years, a growing number of works by Kim have drawn a connection between systems of notation of the sort used in music and dance and the artist’s own graphical representation of sign language. In her works and lecture performances, the artist deftly explores the fundamental structures of American Sign Language (ASL), celebrating its inherent beauty and its powerful role as a part of Deaf identity. Besides the aesthetic qualities of non-auditive modes of communication, processes of translation in all their facets are another focus in Kim’s work. Her practice spans multiple languages, tracking points of convergence and divergence between ASL and English and often occupying both at once. Far from being fixed and immutable, language—spoken and signed, written and sung—is fluid and perpetually changing.

At the Secession, the artist presents new works in which she continues her exploration with the themes of echo and debt. The echo is an emblem for the time lags, superimpositions, and distortions that, for the artist, characterize the process of communicating with hearing people and life in a society dominated by them: communication facilitated by sign language interpreters (as well as ancillary forms of writing) is distorted by pauses, waiting, and the uncertainty of how faithfully a message will ultimately be “translated.”

In her studies into debt, she examines the social conventions for which the incursion of liabilities is an unquestioned part of life; the pressure to repay debts is accepted as its inevitable flipside. Her perception of a large difference between the economic orders of her native U.S. and Germany, where she has chosen to live, has fueled this interest. Still, Kim emphasizes that disability rights are considerably more progressive in the U.S. than, say, in Europe. Taking an interest in debt broadly conceived, she explores social liabilities, but also private obligations in the form of commitments and responsibilities.

Kim’s drawings combine writing and image, the two dimensions of the sheet, with the three dimensions of space and body. Words spelled on the pictures such as “HAND” and “PALM” refer to the components of sign language. That is why the shapes, far from being coincidental, are a result of this relationship.

Hewing to the artist’s customary black-and-white, the composition of the exhibition, comprising a monumental wall painting, videos, and drawings, is rhythmical and melodic yet also dramatic, alternating between noisy and quiet zones. The mural Prolonged Echo, which is based on the charcoal drawing Long Echo (2022) and extends across the room’s entire rear wall, positively shouts at us and overwhelms us with its physical presence, while the drawings from the series Echo Trap are in rhythmical and almost throbbing motion. On a smaller scale, the room’s energy is also palpable in each of the large-format charcoal drawings: the black areas thickly coated with charcoal are inhomogeneous, revealing considerable depth and showing traces of the creative process in the form of impressions made by the crayon and smudges left by the artist’s hand.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is the two-channel video work Cues on Point (2022), which is making its public debut at the Secession. It is part of Kim’s ongoing reflection on her appearance at the 2020 Super Bowl, where the artist was invited to perform the American national anthem The Star-Spangled Banner and America the Beautiful in American Sign Language together with the singers Demi Lovato and Yolanda Adams in the stadium and for a hundred million TV viewers before the beginning of the game. In the middle of her performance, the cameras for the ASL-dedicated broadcast panned away from her and toward the athletes, making it impossible for Deaf people to follow the songs, a big disappointment for the artist and many others. Rather than showing the artist’s recitation as such, the two videos lay out the code of cues she had developed with the ASL interpreter Beth Staehle, who signaled to her during the performance to keep her in sync with the vocalists.

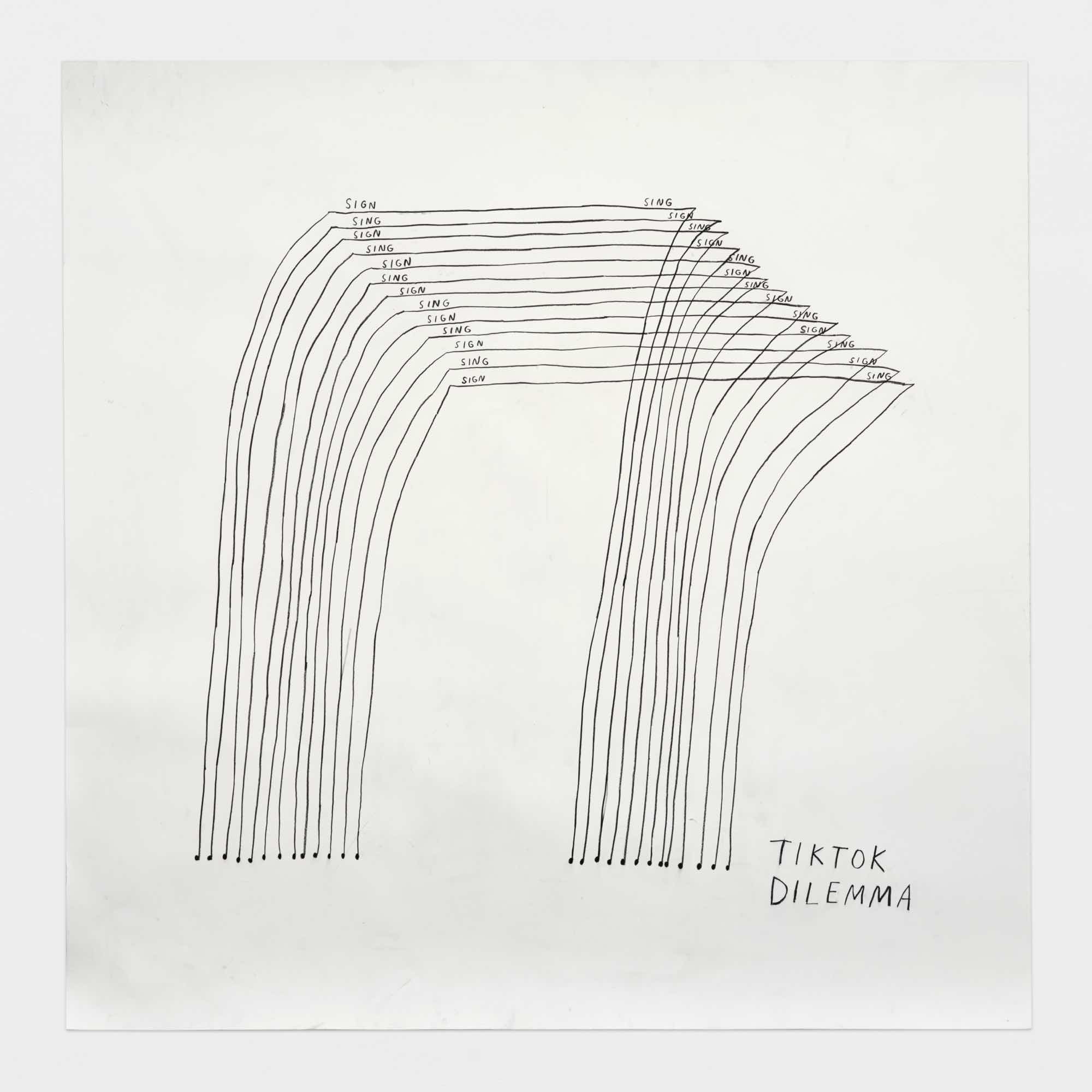

In the drawing Sign Sing, Kim points up the similarities as well as differences between singing and signing—both are manifestly forms of expression, but not at all the same thing. Her experience, whether during the Super Bowl performance or in her observations of a TikTok trend that has hearing influencers recite popular songs in incorrect sign language (the subject of the work Tiktok Dilemma, 2022), people identify sound and signifier without regard to the fact that the one mode of expression oppresses the other.

*In the use of the capitalisation of Deaf we follow the artist, who is referring to Carol Padden and Tom Humphries, Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture (1988), where they write: “We use the lowercase deaf when referring to the audiological condition of not hearing, and the uppercase Deaf when referring to a particular group of deaf people who share a language – American Sign Language (ASL) – and a culture.”

Curated by Bettina Spörr

Language, sound, body, identity and diaspora, translation, hierarchization, principles of exclusion, and societal norms: these are some of the vital concerns to which the artist dedicates herself in her formally diverse output. Many of her works share with the audience how it feels to be structurally and systematically excluded from the hearing majority community; to be forever subject to the rules of others and have to fight for opportunities that are available by default to the hearing. Kim’s art is unmistakably political, at its core demanding greater visibility for Deaf people* and wider recognition of disability access writ large.

Sign language is a constant theme on the formal and aesthetic level as well as the level of content. In recent years, a growing number of works by Kim have drawn a connection between systems of notation of the sort used in music and dance and the artist’s own graphical representation of sign language. In her works and lecture performances, the artist deftly explores the fundamental structures of American Sign Language (ASL), celebrating its inherent beauty and its powerful role as a part of Deaf identity. Besides the aesthetic qualities of non-auditive modes of communication, processes of translation in all their facets are another focus in Kim’s work. Her practice spans multiple languages, tracking points of convergence and divergence between ASL and English and often occupying both at once. Far from being fixed and immutable, language—spoken and signed, written and sung—is fluid and perpetually changing.

At the Secession, the artist presents new works in which she continues her exploration with the themes of echo and debt. The echo is an emblem for the time lags, superimpositions, and distortions that, for the artist, characterize the process of communicating with hearing people and life in a society dominated by them: communication facilitated by sign language interpreters (as well as ancillary forms of writing) is distorted by pauses, waiting, and the uncertainty of how faithfully a message will ultimately be “translated.”

In her studies into debt, she examines the social conventions for which the incursion of liabilities is an unquestioned part of life; the pressure to repay debts is accepted as its inevitable flipside. Her perception of a large difference between the economic orders of her native U.S. and Germany, where she has chosen to live, has fueled this interest. Still, Kim emphasizes that disability rights are considerably more progressive in the U.S. than, say, in Europe. Taking an interest in debt broadly conceived, she explores social liabilities, but also private obligations in the form of commitments and responsibilities.

Kim’s drawings combine writing and image, the two dimensions of the sheet, with the three dimensions of space and body. Words spelled on the pictures such as “HAND” and “PALM” refer to the components of sign language. That is why the shapes, far from being coincidental, are a result of this relationship.

Hewing to the artist’s customary black-and-white, the composition of the exhibition, comprising a monumental wall painting, videos, and drawings, is rhythmical and melodic yet also dramatic, alternating between noisy and quiet zones. The mural Prolonged Echo, which is based on the charcoal drawing Long Echo (2022) and extends across the room’s entire rear wall, positively shouts at us and overwhelms us with its physical presence, while the drawings from the series Echo Trap are in rhythmical and almost throbbing motion. On a smaller scale, the room’s energy is also palpable in each of the large-format charcoal drawings: the black areas thickly coated with charcoal are inhomogeneous, revealing considerable depth and showing traces of the creative process in the form of impressions made by the crayon and smudges left by the artist’s hand.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is the two-channel video work Cues on Point (2022), which is making its public debut at the Secession. It is part of Kim’s ongoing reflection on her appearance at the 2020 Super Bowl, where the artist was invited to perform the American national anthem The Star-Spangled Banner and America the Beautiful in American Sign Language together with the singers Demi Lovato and Yolanda Adams in the stadium and for a hundred million TV viewers before the beginning of the game. In the middle of her performance, the cameras for the ASL-dedicated broadcast panned away from her and toward the athletes, making it impossible for Deaf people to follow the songs, a big disappointment for the artist and many others. Rather than showing the artist’s recitation as such, the two videos lay out the code of cues she had developed with the ASL interpreter Beth Staehle, who signaled to her during the performance to keep her in sync with the vocalists.

In the drawing Sign Sing, Kim points up the similarities as well as differences between singing and signing—both are manifestly forms of expression, but not at all the same thing. Her experience, whether during the Super Bowl performance or in her observations of a TikTok trend that has hearing influencers recite popular songs in incorrect sign language (the subject of the work Tiktok Dilemma, 2022), people identify sound and signifier without regard to the fact that the one mode of expression oppresses the other.

*In the use of the capitalisation of Deaf we follow the artist, who is referring to Carol Padden and Tom Humphries, Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture (1988), where they write: “We use the lowercase deaf when referring to the audiological condition of not hearing, and the uppercase Deaf when referring to a particular group of deaf people who share a language – American Sign Language (ASL) – and a culture.”

Curated by Bettina Spörr