Elaine Reichek

Now If I Had Been Writing This Story

13 Apr - 03 Jun 2018

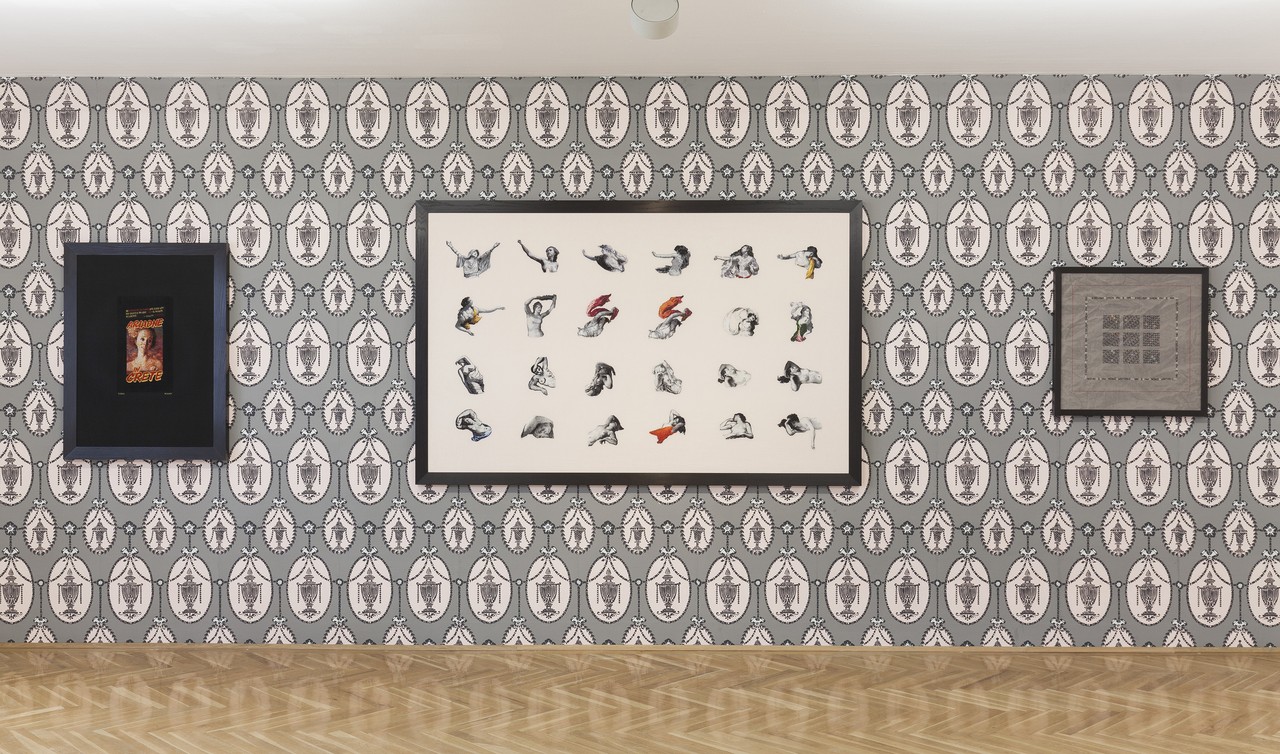

Elaine Reichek, Now If I Had Been Telling That Story, exhibition view Secession 2018, Courtesy of the artist, Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Los Angeles and Marinaro, New York, Photo: Oliver Ottenschläger

For more than four decades, Elaine Reichek has been working on a critical and feminist reading of historical texts and images. The analytical engagement with narratives from myth and literature and the reflection on their social function as a medium of cultural cohesion run through the artist’s oeuvre like the thread that Ariadne gave to Theseus so that he would find his way out of the Minotaur’s labyrinth.

In her first solo exhibition in Austria, the New York-based artist presents works from the past eleven years that explore the figures of the “Minoan girls” and the stories of lust, seduction, cruelty, and betrayal associated with them: Europa, Pasiphaë, Phaedra, and Ariadne. Although their tragic fates are key to the narratives in which they appear, they are often seen as supporting characters; the heroes are invariably men. Reichek, by contrast, puts the spotlight on the women, examining their complex characters by compiling different interpretations and depictions, and assembling eclectic arrangements of elements from visual art and literature to break through overly narrow constructions: in the artist’s hands, appropriation becomes a strategy of emancipation.

Reichek employs a wide variety of media and engages works of art and literature from all eras in creative dialogue. Textile techniques such as embroidery and knitting as well as conceptual methods, photography, and various printing processes have been central to her practice since the 1970s. Now If I Had Been Writing This Story builds on her earlier cycles Minoan Girls (2012–16) and Ariadne’s Thread (2008–12). The exhibition’s title is borrowed from Phèdre, a poem by the English writer Stevie Smith in which she refuses to accept Phaedra’s tragic fate and musters the power of words to at least lend expression to the desire for a happier outcome.

Not by accident, what holds Reichek’s work together on the formal and conceptual levels is the thread—in the figurative as well as literal sense: unspooling Ariadne’s thread lets her unfold the story of the labyrinth, while the fine thread used in embroidery interweaves images and selected passages of text in scintillating visual compositions. The works on view in the exhibition integrate quotations from the art of Gustav Klimt, André Masson, Henri Matisse, and others with references to texts by Stevie Smith, Erika Mumford, Henry de Montherlant, Giorgio de Chirico, and the fifth-century Byzantine poet Nonnus.

Reichek deftly intertwines her ongoing preoccupation with myths as archetypal stories with a practice that is essentially repetitive: embroidering.

“Just as sewing loops a thread around and around a substrate of fabric, so we continually reenact and recycle these myths over the centuries. And just as sewing creates an unseen backstory on the other side of the cloth, so these ancient myths—primal narratives that recite basic motivations—have proved ever open to analysis, interpretation, and deconstruction. The unraveling and reconstitution of stories and motifs is a very old process, no matter how much we imagine it to be a modernist or contemporary phenomenon.” (Excerpt from Elaine Reichek’s text for her artist book that is published by the Secession on occasion of her exhibition)

Immediately recognizing the structural resemblance between rasterized digital images and embroidery or knitting pattern charts, Reichek incorporated digital media into her creative praxis. Like a pixel, the stitch is the basic building block of visual transmission in her work: a pixelated image resembles an embroidery chart, just as the stitches in a hand-sewn embroidery point back to a JPEG trawled from the Internet or scanned from a printed source. Although digital technology has sped up and expanded the possibilities for research, translation, and production, Reichek’s works remain material objects, rooted in the history of thread as a medium.

Elaine Reichek’s artist’s book, published on the occasion of the exhibition, is a decorative archival storage box in the design of the Hamilton Urns—one of the earliest examples of American neo-classical wallpaper models—that unpacks her exhibition both physically and conceptually. Inside are two different kinds of books: A standard book includes all the works in the exhibition and an essay by the artist. Then, four accordion-style leporellos explore the most recent piece, Toutes les filles (2016–17), unfolding to reveal each of its 24 motifs and their art-historical sources.

In the past few years, the hand-printed wallpaper featuring the Hamilton Urns pattern has become almost a trademark feature of Reichek’s exhibitions; in our show, it also appears as a backdrop on the walls. This version with its unusual palette was manufactured specifically for the occasion.

In her first solo exhibition in Austria, the New York-based artist presents works from the past eleven years that explore the figures of the “Minoan girls” and the stories of lust, seduction, cruelty, and betrayal associated with them: Europa, Pasiphaë, Phaedra, and Ariadne. Although their tragic fates are key to the narratives in which they appear, they are often seen as supporting characters; the heroes are invariably men. Reichek, by contrast, puts the spotlight on the women, examining their complex characters by compiling different interpretations and depictions, and assembling eclectic arrangements of elements from visual art and literature to break through overly narrow constructions: in the artist’s hands, appropriation becomes a strategy of emancipation.

Reichek employs a wide variety of media and engages works of art and literature from all eras in creative dialogue. Textile techniques such as embroidery and knitting as well as conceptual methods, photography, and various printing processes have been central to her practice since the 1970s. Now If I Had Been Writing This Story builds on her earlier cycles Minoan Girls (2012–16) and Ariadne’s Thread (2008–12). The exhibition’s title is borrowed from Phèdre, a poem by the English writer Stevie Smith in which she refuses to accept Phaedra’s tragic fate and musters the power of words to at least lend expression to the desire for a happier outcome.

Not by accident, what holds Reichek’s work together on the formal and conceptual levels is the thread—in the figurative as well as literal sense: unspooling Ariadne’s thread lets her unfold the story of the labyrinth, while the fine thread used in embroidery interweaves images and selected passages of text in scintillating visual compositions. The works on view in the exhibition integrate quotations from the art of Gustav Klimt, André Masson, Henri Matisse, and others with references to texts by Stevie Smith, Erika Mumford, Henry de Montherlant, Giorgio de Chirico, and the fifth-century Byzantine poet Nonnus.

Reichek deftly intertwines her ongoing preoccupation with myths as archetypal stories with a practice that is essentially repetitive: embroidering.

“Just as sewing loops a thread around and around a substrate of fabric, so we continually reenact and recycle these myths over the centuries. And just as sewing creates an unseen backstory on the other side of the cloth, so these ancient myths—primal narratives that recite basic motivations—have proved ever open to analysis, interpretation, and deconstruction. The unraveling and reconstitution of stories and motifs is a very old process, no matter how much we imagine it to be a modernist or contemporary phenomenon.” (Excerpt from Elaine Reichek’s text for her artist book that is published by the Secession on occasion of her exhibition)

Immediately recognizing the structural resemblance between rasterized digital images and embroidery or knitting pattern charts, Reichek incorporated digital media into her creative praxis. Like a pixel, the stitch is the basic building block of visual transmission in her work: a pixelated image resembles an embroidery chart, just as the stitches in a hand-sewn embroidery point back to a JPEG trawled from the Internet or scanned from a printed source. Although digital technology has sped up and expanded the possibilities for research, translation, and production, Reichek’s works remain material objects, rooted in the history of thread as a medium.

Elaine Reichek’s artist’s book, published on the occasion of the exhibition, is a decorative archival storage box in the design of the Hamilton Urns—one of the earliest examples of American neo-classical wallpaper models—that unpacks her exhibition both physically and conceptually. Inside are two different kinds of books: A standard book includes all the works in the exhibition and an essay by the artist. Then, four accordion-style leporellos explore the most recent piece, Toutes les filles (2016–17), unfolding to reveal each of its 24 motifs and their art-historical sources.

In the past few years, the hand-printed wallpaper featuring the Hamilton Urns pattern has become almost a trademark feature of Reichek’s exhibitions; in our show, it also appears as a backdrop on the walls. This version with its unusual palette was manufactured specifically for the occasion.