Jean-Luc Moulène

The Secession Knot (5.1)

06 Apr - 18 Jun 2017

Jean-Luc Moulène, The Secession Knot (5.1)

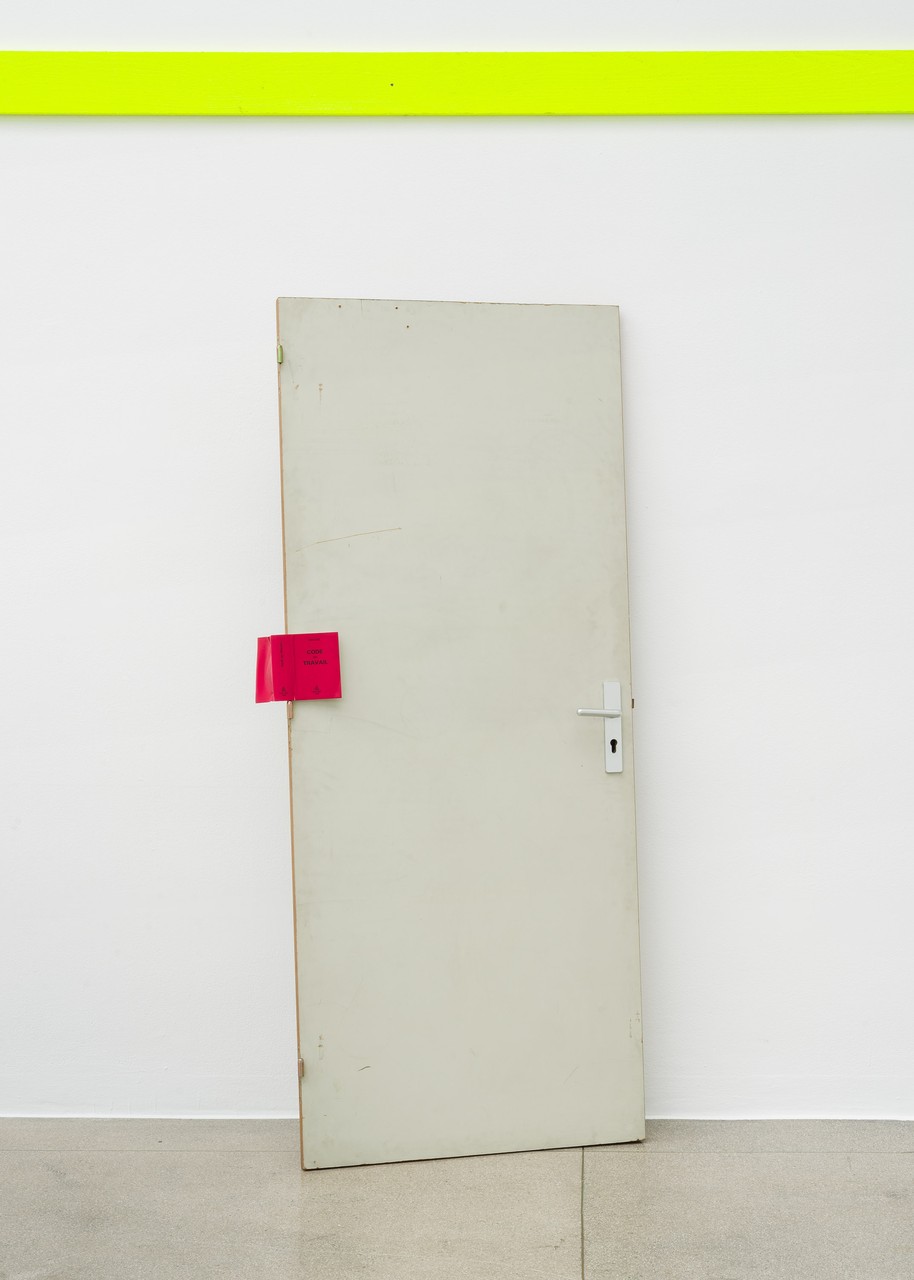

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Jean-Luc Moulène, The Secession Knot (5.1)

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Jean-Luc Moulène, The Secession Knot (5.1)

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Jean-Luc Moulène, The Secession Knot (5.1)

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Jean-Luc Moulène, The Secession Knot (5.1)

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Jean-Luc Moulène, The Secession Knot (5.1)

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Jean-Luc Moulène, The Secession Knot (5.1)

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Jean-Luc Moulène, The Secession Knot (5.1)

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Exhibition view at Secession, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Iris Ranzinger

JEAN-LUC MOULÈNE

The Secession Knot (5.1)

6 April – 18 June 2017

What goes beyond the exhibition as an artwork is the program as an artwork. (Jean-Luc Moulène)

For over thirty years, in an oeuvre that is broadly diversified in both subject and mediums employed, Jean-Luc Moulène has been exploring the nature of artistic work and what it means. He works with a variety of different materials ranging from those that are industrially produced to those that are organic or found and in mediums such as photography, film, painting, sculpture and installation. Moulène values interdisciplinary collaboration especially in relation to works that are located at the interface between art and industrial design. In principle the awareness of the relationship of artwork as commodity and part of the circulation of goods runs through the entire work of the artist. In this respect the artist’s sensibility is indicated by the definition of his sculptures as objects and the designation of his works as products. Just as Moulène perceives photography as oscillating between medium and art, he regards his objects as enjoying a status between sculpture and product and, on the other hand, his photographs as post-photographic documents.

Moulène, who describes himself as a poet, is also inspired by mathematics – set theory, to be precise – which he sees as providing a metaphor for social space. Many of his works are characterised by observation and analysis of this social space and its forms and overlappings with individual spaces. In recent years Moulène’s praxis has become increasingly object related and material specific. The special qualities of a material and its unique working qualities prompt him to push it to its limits. This struggle with form and expression illustrates Moulène’s notion of art as a zone of conflict: from his point of view the domain of art is not peaceful. For him an artwork always contains a ‘yes’ and a ‘no’ and it is the task of the viewer to find and define their own position.

One exhibition gives rise to the next, and so the work on view at the Secession contains echoes of a show that recently closed at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in which Moulène explored the theme of “resemblance and knots.” A “spatial knot” of timber panels alternately painted black and yellow constitutes the core of Moulène’s display in the Secession’s main gallery. The convoluted wooden ribbon sprawls over walls, ceilings, and floors, crossing itself a total of five times – this fivefold intersection is referred to by the “5” in the title. The wooden band structures the gallery and divides it into segments with different spatial qualities in which Moulène places objects, most of which were created on the scene.

The alternation of black and yellow generates a positively hypnotic rhythm that is reinforced by different lengths of the wood elements and the materiality and quality of the paints. Each corner, each element stretching across a section of the space represents a specific constructive problem that calls for an individual solution. The black wood parts owe their saturated color and intense sheen to a double coat of tar paint, while the radiance of the yellow elements is due to a bold neon paint. Both colors moreover carry symbolic meanings: bitumen stands for physical matter, while neon yellow is associated with the written word and language. Taken together, they are the most striking and hence the most efficient color combination in typography.

The knot—its mathematical function as well as its symbolic significance—has been an ongoing interest in Moulène’s art. He translates knot theory, a mathematical system for the description of intricate situations, into art in an effort to deal with its complexity. As Moulène sees it, the knot is a principle that runs counter to the deeply entrenched binarism of contemporary thinking: it has neither inside nor outside, neither beginning nor end. The knot at the Secession ostensibly organizes the space but is ultimately a metaphor. Moulène describes the interrelation between architecture and knot as one of master and servant. In the final analysis, it is freedom itself that is at stake.

Conceived on occasion of the exhibition, the artist’s book Brèves is both an exhibit in the show and the “program” underlying the objects on display, which spread out in a mysterious and ephemeral array within the fields delineated by the spatial knot, taking up and elaborating on ideas and forms of the exhibition. The human body and its absence, volumes, surfaces, and boundaries—some of them contested—are recurrent motifs. “Brèves”—the word designates short notices in printed newspapers—is Moulène’s term for his redacted newspaper images. Equipped with a four-color ballpoint pen, the artist picked up a habit a few years ago of passing his time by altering pictures that struck him as interesting for their content or their formal qualities, complementing them by reiterating motifs, extending forms, or painting out elements. The subjects cover a broad spectrum, from highly political issues including global protests and environmental disasters across French domestic politics and science and research to images that are of formal and aesthetic relevance to the artist.

The Secession Knot (5.1)

6 April – 18 June 2017

What goes beyond the exhibition as an artwork is the program as an artwork. (Jean-Luc Moulène)

For over thirty years, in an oeuvre that is broadly diversified in both subject and mediums employed, Jean-Luc Moulène has been exploring the nature of artistic work and what it means. He works with a variety of different materials ranging from those that are industrially produced to those that are organic or found and in mediums such as photography, film, painting, sculpture and installation. Moulène values interdisciplinary collaboration especially in relation to works that are located at the interface between art and industrial design. In principle the awareness of the relationship of artwork as commodity and part of the circulation of goods runs through the entire work of the artist. In this respect the artist’s sensibility is indicated by the definition of his sculptures as objects and the designation of his works as products. Just as Moulène perceives photography as oscillating between medium and art, he regards his objects as enjoying a status between sculpture and product and, on the other hand, his photographs as post-photographic documents.

Moulène, who describes himself as a poet, is also inspired by mathematics – set theory, to be precise – which he sees as providing a metaphor for social space. Many of his works are characterised by observation and analysis of this social space and its forms and overlappings with individual spaces. In recent years Moulène’s praxis has become increasingly object related and material specific. The special qualities of a material and its unique working qualities prompt him to push it to its limits. This struggle with form and expression illustrates Moulène’s notion of art as a zone of conflict: from his point of view the domain of art is not peaceful. For him an artwork always contains a ‘yes’ and a ‘no’ and it is the task of the viewer to find and define their own position.

One exhibition gives rise to the next, and so the work on view at the Secession contains echoes of a show that recently closed at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in which Moulène explored the theme of “resemblance and knots.” A “spatial knot” of timber panels alternately painted black and yellow constitutes the core of Moulène’s display in the Secession’s main gallery. The convoluted wooden ribbon sprawls over walls, ceilings, and floors, crossing itself a total of five times – this fivefold intersection is referred to by the “5” in the title. The wooden band structures the gallery and divides it into segments with different spatial qualities in which Moulène places objects, most of which were created on the scene.

The alternation of black and yellow generates a positively hypnotic rhythm that is reinforced by different lengths of the wood elements and the materiality and quality of the paints. Each corner, each element stretching across a section of the space represents a specific constructive problem that calls for an individual solution. The black wood parts owe their saturated color and intense sheen to a double coat of tar paint, while the radiance of the yellow elements is due to a bold neon paint. Both colors moreover carry symbolic meanings: bitumen stands for physical matter, while neon yellow is associated with the written word and language. Taken together, they are the most striking and hence the most efficient color combination in typography.

The knot—its mathematical function as well as its symbolic significance—has been an ongoing interest in Moulène’s art. He translates knot theory, a mathematical system for the description of intricate situations, into art in an effort to deal with its complexity. As Moulène sees it, the knot is a principle that runs counter to the deeply entrenched binarism of contemporary thinking: it has neither inside nor outside, neither beginning nor end. The knot at the Secession ostensibly organizes the space but is ultimately a metaphor. Moulène describes the interrelation between architecture and knot as one of master and servant. In the final analysis, it is freedom itself that is at stake.

Conceived on occasion of the exhibition, the artist’s book Brèves is both an exhibit in the show and the “program” underlying the objects on display, which spread out in a mysterious and ephemeral array within the fields delineated by the spatial knot, taking up and elaborating on ideas and forms of the exhibition. The human body and its absence, volumes, surfaces, and boundaries—some of them contested—are recurrent motifs. “Brèves”—the word designates short notices in printed newspapers—is Moulène’s term for his redacted newspaper images. Equipped with a four-color ballpoint pen, the artist picked up a habit a few years ago of passing his time by altering pictures that struck him as interesting for their content or their formal qualities, complementing them by reiterating motifs, extending forms, or painting out elements. The subjects cover a broad spectrum, from highly political issues including global protests and environmental disasters across French domestic politics and science and research to images that are of formal and aesthetic relevance to the artist.